The editor of Monthly Review responds to ‘socialists’ who view the environmental crisis as a problem of technology, not a fundamental rift in society’s relationship with nature.

by Ian Angus

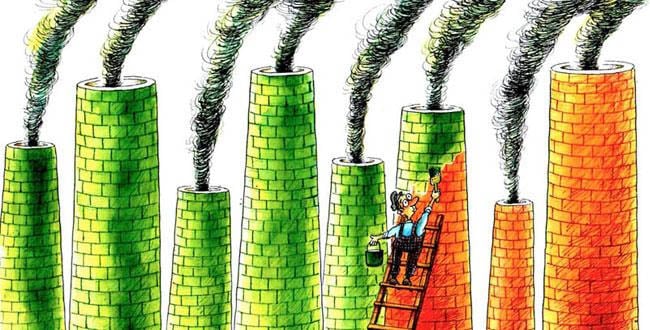

A month ago in this column, I wrote that the latest issue of Jacobin magazine, which purports to address the environmental crisis, “is definitely on the wrong track.” Although the magazine says it favors eco-socialism, “there is nothing in this issue resembling an ecosocialist analysis or program.” Instead it features article after article endorsing “ecomodernism with a leftish veneer” — techno-fixes that don’t address the root causes of the crisis.

My short article touched on only a few key points, so I am very pleased to see that John Bellamy Foster, author of Marx’s Ecology and many other ecosocialist books, has taken up the subject in depth. In “The Long Ecological Revolution,” a masterful article in the November issue of Monthly Review, he writes:

“No revolutionary movement exists in a vacuum; it is invariably confronted with counterrevolutionary doctrines designed to defend the status quo. In our era, ecological Marxism or ecosocialism, as the most comprehensive challenge to the structural crisis of our times, is being countered by capitalist ecomodernism — the outgrowth of an earlier ideology of modernism, which from the first opposed the notion that economic growth faced natural limits. If ecosocialism insists that a revolution to restore a sustainable human relation to the earth requires a frontal assault on the system of capital accumulation—and that this can only be accomplished by more egalitarian social relations and more consciously coevolutionary relations to the earth — ecomodernism promises precisely the opposite. ….

“It is dispiriting but not altogether surprising that some self-styled socialists have jumped on the ecomodernist bandwagon, arguing against most ecologists and ecosocialists that what is required to address climate change and environmental problems as a whole is simply technological change, coupled with progressive redistribution of resources. Here again, the Earth System crisis is said not to demand fundamental changes in social relations and in the human metabolism with nature. Rather it is to be approached in instrumentalist terms as a formidable barrier to be overcome by means of extreme technology. …

“If this stance is ‘socialist,’ it is only in the supposedly progressive, ecomodernist sense of combining state-directed technocratic planning and market regulation with proposals for more equitable income distribution. In this vision, ecological necessities are once again subordinated to notions of economic and technological development that are treated as inexorable. Nature is not a living system to be defended, but a foe to be conquered.”

Foster continues with a detailed critique of articles in Jacobin‘s environment issue, focusing in particular on the articles by Leigh Phillips and Michael Rozworski, Peter Frase, and Christian Parenti, all of whom promote “Promethean views [that] are designed to avoid the reality of the contemporary social and ecological crisis — namely, that revolutionary changes in the existing relations of production are unavoidable.”

This is a powerful and much-needed response to ideas that are gaining traction in some sections of the left. It is an important contribution to the ecosocialist movement, and must-reading for everyone concerned about the fight for sustainable human development in our time.

Click here to read John Bellamy Foster’s article.

Foster’s critique of the Jacobin issue on the environment is a model of Marxist criticism — thorough, fair, and clearly distinguishes our eco socialist approach to the problem from liberal/green capitalist approaches.

That said, Ethan’s and Michael’s ad hominem attack on Bhaskar Sunkara and snide dismissal of the contributors to that Jacobin issue is unfair, sectarian and hurts our cause. What if in print I dismissed the editors of MR as unreconstructed Stalinists because of their defense of Stalinist governments in Cuba, China, and in the past the Soviet Union? I could easily show why state planning + party-bureaucratic dictatorship do not = any kind of socialism, at least as Marx and the tradition of non-Stalinist bottom-up democratic socialists have conceived the term.

But I don’t want to pick this fight. I prefer to work with people who describe themselves as ecosocialists and focus on what unites us rather than what divided us in the past. I feel the same toward Jacobin. Bhaskar Sunkara has, I must say, done what none of us has done — and that is to draw large numbers of political young people to study groups around the magazine. I’ve been to Jacobin meet ups where 70 or more people show up, divide into groups and discuss various articles, then go out for beer to carry on the discussion. I gave a talk to a group of 30 a while ago. This is the sort of thing we should be doing. Why don’t you challenge the Jacobin editors to a discussion/debate instead of trashing them?

Thanks for this Ian. Your work and John’s are so necessary now. Jacobin has done the left no favors, but it has done no harm to capital, that is for sure.

Not to take Jacobin’s side in this debate – I don’t think it’s necessary to throw scare quotes around the word ‘socialist’, as if they don’t deserve the title (or epithet, as a huge number of Americans still consider it).

Ethan, I would say that it would be a real stretch to call Leigh Phillips, Christian Parenti, Conor Kilpatrick, Angela Nagle, and the master hustler himself, Sunkara, socialists. Certainly not in the sense that MR’s founders, editors, and staff think of socialism. Left liberals, maybe. And most of our writers, for example, the late Istvan Meszaros, would heap scorn on their claim to be socialists. Of course, in any given circumstance, these people might be allies (though Phillips and a couple others are reactionaries and will never be our allies), but that is a different matter.