Ian Angus reviews two very different books on the life of Karl Marx’s closest collaborator

If I could meet and spend some time with just one of the men and women who built the socialist movement in the past two centuries, I would choose Friedrich Engels, a brilliant thinker and writer and lifelong partisan of the oppressed, but also a very human and humane man who loved good companions, good food, good drink and great ideas.

He was born on November 28, 1820, so to mark the 194th annversary of his birth, here is a book review I wrote five years ago.

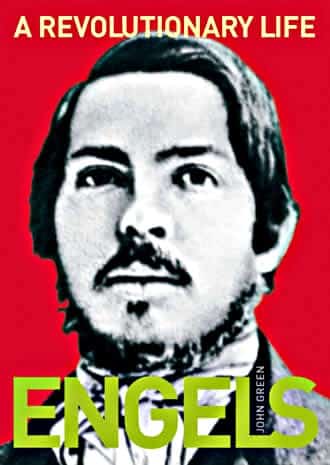

John Green

John Green

Engels: A Revolutionary Life

Artery Publications, 2008

Tristram Hunt

Marx’s General: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels

Macmillan/Metropolitan, 2009

reviewed by Ian Angus

Socialist Voice, August 2009

Most people on the left know that Friedrich Engels was co-author of the Communist Manifesto and Karl Marx’s lifelong collaborator. But few of today’s radicals know much more than that about the man who built barricades and fought a guerrilla war in Germany in the 1848-49 revolution, the indefatigable organizer who played a decisive role in building the Marxist current from a handful of exiles in the 1850s into the dominant trend in the international working class movement by the time of his death in 1895.

They can scarcely be blamed for their lack of knowledge: it hasn’t been easy to learn about Engels’ life. In the 110 years after he died, only two substantial biographies were published in English – by Gustav Mayer in 1936, and by W.O. Henderson in 1967 – and both have long been out of print.

So socialists can only be pleased by the arrival of two new biographies of Karl Marx’s comrade, and indeed, these books have been warmly welcomed by socialist reviewers. However, our pleasure at the publication of two books on a neglected socialist leader should not blind us to the fact that neither is the comprehensive study that Engels really deserves.

Both are accounts of Engels’ life – not his life and ideas. Each discusses aspects of his political views and briefly summarizes some of his major works, but neither does so in detail. That’s a serious weakness in biographies of a man who, as Green writes, “enjoyed nothing more than a lively debate, the clash of ideas and argument.”

We can hope that other writers will correct the balance, but for now these are the most accessible accounts we have of Engels’ life. They cover similar ground, of course, but they differ in emphasis. Green focuses on Engels as a builder and leader of the revolutionary left, while Hunt stresses his personal life, particularly the personal and political sacrifices he made to support Marx.

Engels: A Revolutionary Life

All by itself, John Green’s account of Engels’ involvement in the 1848-49 revolutions in France and Germany make Engels: A Revolutionary Life worth reading. Anyone who thinks of Engels only as a grey-bearded socialist elder will be surprised and inspired by this account of a twenty-something activist who put his life on the line for his ideas.

Green also describes Engels’ role in building and guiding the international socialist movement in the last two decades of his life. From his home in London, Engels kept up a voluminous correspondence in multiple languages – he prided himself on always responding in the languages of his correspondents – answering questions, advising, and criticizing.

Green is critical of the role Marx and Engels played in debates in the workers movement, complaining of their “almost pathological resistance” to ideas other than their own.

“In their intolerance of differing approaches to creating the basis for a socialist society and their vituperative lashing of those who think differently, one can see the germ of the sectarian in-fighting, the dogmatism and intolerance of dissent that will plague communist movements of the twentieth century.”

And yet Green admits that what he calls their “perpetual cavilling and proffering of advice” to the German socialists did “persuade the party eventually to adopt many of their fundamental principles.” Obviously Marx and Engels were doing something right!

What Green fails to understand is that far from presaging the sectarianism of later grouplets, in most of these disputes Marx and Engels were arguing against the sectarians of their day. They were intolerant of those who tried to divert the workers’ movement onto side roads and dead ends, and they argued strongly that “every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programmes.”

Green says that his goal was to “rescue the man Friedrich Engels from the suffocating embrace of academia and to remove the layers of clutter and detailed overload that have kept him hidden.” Despite its political limitations, Engels: A Revolutionary Life largely does that, providing a valuable portrait of a man who committed himself to the revolutionary cause in his early twenties and never looked back.

Marx’s General

From a strictly political perspective, the strongest part of Marx’s General, which was published in England as The Frock-Coated Communist, is its discussion of the philosophical debates in Germany in the early 1840s. Hunt’s account of the intense intellectual ferment from which Marxism emerged is the clearest and most concise I’ve read.

But his main focus is “the rich contradiction and limitless sacrifice which marked [Engels’] long life” – in particular, the years from 1851 to 1869, when Engels was employed in his family’s cotton business, doing work he hated intensely, in order to support Marx while the latter researched and wrote Capital. For nearly 19 years, Engels held his tongue in Manchester business circles during long working days, while meeting (and carousing) with socialists and other working class militants late into the night.

Hunt, it must be said, sees this as a greater contradiction than Engels himself did, but his account does illuminate just how committed Engels was to his and Marx’s joint lifetime project.

Hunt’s focus on Engels’ personal life occasionally leads him into sensationalism. As a young man in France and Belgium, Engels wrote that he enjoyed the company of “grisettes,” which Hunt inaccurately translates as “prostitutes.” Grisettes were actually young working class women, mainly in the garment industry, who were active in bohemian and left circles. As in the 1960s, an open attitude towards sex was common in the European left in the 1840s, but only conservative prigs and prudes – people Engels detested – equated sexual freedom with prostitution.

Like Green, but with much greater indignation, Hunt repeats the often-told story that Marx had an illegitimate son in 1851, and that Engels pretended to be the father to protect Marx’s marriage. Only a reader who goes to the sources cited in Hunt’s footnotes will learn that the entire story is based on one letter written by an unreliable witness in 1898 – and that other evidence makes the story unlikely. (See http://marxmyths.org/terrell-carver/article.htm)

Fortunately, salacious gossip doesn’t dominate Marx’s General, which in total shows a very human and humane man who loved good companions, good food, good drink and great ideas – a man whose life gives the lie to reactionary claims that socialists are cheerless fanatics.

Engels versus Marx?

In the twentieth century, Engels was frequently accused of revising, watering down, or otherwise corrupting Marxism. Depending on which critic you read, Engels was guilty of being too Hegelian or not Hegelian enough, of excessive scientism or not understanding science, of responsibility for social-democratic electoralism or for Stalinist totalitarianism.

As Sebastiano Timpanaro wrote in 1970, it seems that radical academics always start by blaming Engels for the parts of Marxism they disagree with:

“In all of these operations, there is a need for somebody on whom everything which Marxists, at that particular moment, are asking to get rid of can be dumped.… Marx turns out to be free of all these vices, provided one knows how to ‘read’ him. It was Engels who, in his zeal to simplify and vulgarize Marxism, contaminated it.” (On Materialism)

Since neither of the new biographies tries to provide a thorough account of Engels’ ideas, it isn’t surprising that neither deals in depth with such charges.

John Green is agnostic on the issue. He accurately describes the Marx-Engels relationship as “a close and long-term collaboration … an apparently perfect symbiosis,” but promptly qualifies that by reporting that nevertheless “there are those who claim to recognise significant and far-reaching differences between the thinking of the two men.” He summarizes some critics’ views, but doesn’t evaluate their criticisms. Would Marx have agreed with what Engels wrote in his controversial Dialectics of Nature? Green just says “we can never know.”

Surprisingly, given that his main interest is Engels’ personality and lifestyle, Tristram Hunt handles this issue much more decisively. He insists that Anti-Dühring, often singled out as proof that Engels misunderstood Marxism, is “the expression of authentic, mature Marxist opinion,” and he ridicules the claim some have made that Marx remained silent about Engels’ errors in order to keep his friendship:

“Whatever mechanical revisions happened to Marxism in the twentieth century, it is a misreading of the Marx-Engels relationship to suggest either that Engels knowingly corrupted Marxian theory or that Marx had such a fragile friendship with him that he (Karl Marx!) could not bear to express a disagreement. There is no evidence that Marx was ashamed or concerned about the nature of Engels’ popularization of Marxism.”

We’ll have to wait for a comprehensive defense of Engels, but for now, this response is right on the mark.

Which ‘life’ to choose?

After decades in which there was no life of Engels in print in English, suddenly there are two, with different strengths. Neither is perfect, but both will help to move Engels out of Marx’s shadow and into centre stage where he belongs.

Hunt is an effective writer whose portrait of Engels really brings the man to life. Still, Engels was above all a political thinker and activist, so Hunt’s repeated dismissals of political disputes as pointless squabbling reveal a serious lack of sympathy with his subject. That’s also reflected in his improbable conclusion that Engels would have supported Russia’s Mensheviks against Lenin.

Green is much better on Engels’ role as a revolutionary activist and movement builder, and he devotes more time to Engels’ ideas, although not always insightfully. Unfortunately, his book is not as well written: the narrative jumps confusingly back and forth in time, and Green’s decision to write entirely in the present tense is a constant distraction.