Here’s an interesting historical footnote to the never-ending campaign to convince us that overpopulation is the biggest threat humans face. In the 1970s, the populationists used pulp fiction to publicize their views.

Here’s an interesting historical footnote to the never-ending campaign to convince us that overpopulation is the biggest threat humans face. In the 1970s, the populationists used pulp fiction to publicize their views.

In this century, most populationists present themselves as gentle people who advocate only the most humane measures. But the founder and still top guru of modern overpopulation campaigns is Paul Ehrlich, author of the 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb, who advocated ending food aid to famine-stricken countries and putting anti-fertility drugs into public water systems.

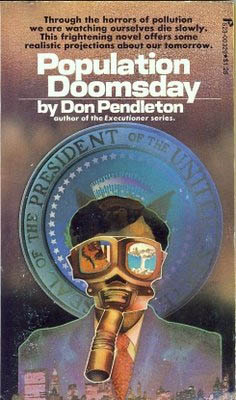

One man who was convinced by Ehrlich was Don Pendleton, a successful writer of ultra-violent pulp novels who was best known for the ‘Executioner’ series, in which his indomitable hero, Mack Bolan, killed literally hundreds of bad guys. Pendleton published 38 Executioner novels in 11 years, then sold the rights to Harlequin Books, which still churns them out by the dozen every year. He later wrote a series about a psychic detective, and non-fiction works that ‘proved’ there is life after death.

In 1970 Pendleton took a break from wiping out the Mafia, to propose wiping out people. The preface of 1989: Population Doomsday (later republished as just Population Doomsday) was a letter to Paul Ehrlich, thanking him for writing The Population Bomb and calling his own book “prophecy and as valid as any educated projections of the best scientific information presently available.”

Ehrlich can’t be held responsible for everything his disciples have said and written, but Pendleton’s book was far from the most extreme. It wasn’t great literature, but it had the virtue of showing where populationist theories can lead: if people are the problem, the solution is to get rid of as many of them as possible, as quickly as possible.

The review below, by Allen Myers, was published in a socialist magazine 43 years ago. If his critique seems simplistic by today’s standards, bear in mind the quality of the work he was criticizing.

—–

Ian

MALTHUS AS FICTION

[Intercontinental Press, January 16, 1971]

1989: Population Doomsday by Don Pendleton.

Bee-Line Books, New York, N. Y. 192 pp. $.95. 1970.

In 1989, on a clear day in New York City, visibility is twenty feet. In every major city in the United States, it is impossible to breathe without a gas mask. Agricultural production has been declining for the past seven years and the country faces a famine. In the rest of the world, conditions are only slightly better, and in some cases worse.

Enter the hero, Royall Hackett ― newly elected president of the United States and environmental defender par excellence. Bang! Smash! Zowie! In four months, Hackett rids the world of the internal combustion engine, industrial production, medical care for the aged and infirm, and ― with the aid of nuclear explosions ― atmospheric pollution. As the sun sets ― visibly for the first time in a decade ― the world is offered a new chance at the Golden Age, provided only that people can learn to get along without transportation, physical comforts, children, and similar frills.

Novels of doomsday are nothing new in American literature, though they generally tend to center on the theme of nuclear destruction. Pendleton’s novel is a reminder of the fact that capitalism knows more than one way of abolishing the human race, although he himself does not see it in those terms.

For Pendleton, the problem is not an anarchic system of production, but too many people. At one point, his hero proclaims:

“Our basic problem is not pollution, Senator, our problem is people. Too damn many people! That may sound callous and politically naïve to you, Senator, but it’s a hard truth that must be faced by 390 million Americans. We have doubled in just twenty-five years. . . . Now you know very well … through the simple facts of basic mathematics, that you cannot double the population of an affluent nation without also doubling housing, classrooms, services, food production and processing, manufacturing, gimmicks and gadgets and all the fripperies of an affluent society – not if you want to maintain that same level of affluence.”

This rehash of long-ago-refuted Malthusian theories is so shallow that at times one almost suspects Pendleton of writing with tongue in cheek ― as, for example, when Hackett orders secondary schools torn down and the land on which they stood planted with crops.

Air is polluted not because there are too many people driving automobiles, but because General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, etc., see no profit in producing a car that doesn’t pollute the atmosphere. The industrial poisons in our rivers are put there by capitalists who find it cheaper than disposing of them safely.

Ridding the world of pollution requires neither the elimination of people, an end to the production of consumer goods, nor the existence of superheroes to take things in hand. It does require a planned economy controlled by the producers ― something we will have, hopefully, long before the arrival of Pendleton’s 1989.