Overpopulation ideology undermined the environmental movement in the 1970s, diverting social protest into harmless channels. To prevent a similar setback today, we must understand populationism’s conservative role, and why it is attractive to a growing number of green activists.

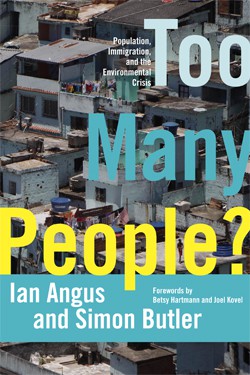

Ian Angus, the editor of Climate and Capitalism, is co-author with Simon butler, of Too Many People? Population, Immigration, and the Environmental Crisis (Haymarket, 2011). He gave the following talk at the Marxism 2012 conference in Toronto in May, and at the Socialism 2012 conference in Chicago in June.

A recording of his Chicago presentation can be heard online at wearemany.org.

As you know, Simon Butler and I have written many articles and an entire book refuting the claim that the environmental crisis is caused by overpopulation and the related idea that environmentalists should make reducing birth rates and immigration a top priority.

I’d like to say that our arguments were so convincing that populationism has disappeared from the green movement, but of course that isn’t so. Far from disappearing, the overpopulation argument is gaining strength, winning new converts among environmentalists.

The promoters of that view like to pose as underdogs. They regularly claim that there is a “taboo” on discussing overpopulation. But in the real world their views get far more coverage than the counter argument. Check the environmentalism section of any large bookstore: you’ll find dozens of books arguing that overpopulation is destroying the earth. You can count the books that disagree on the fingers of one hand.

We saw this dramatically last October. That was the month our book was published, but it was also, by coincidence, the month chosen by United Nations as the symbolic date when the world’s population passed 7 billion.

This gave the populationist lobby — the groups and individuals who attribute social and environmental problems to human numbers — an outstanding opportunity to spread their argument through the mass media, and they took full advantage of it. We were treated to a tsunami of articles and opinion pieces blaming the world’s environmental crises on overpopulation. Numerous environmentalist websites carried articles bemoaning the danger posed by high birth rates.

Global warming, loss of bio-diversity, deforestation, food and water shortages: all of these problems and many more problems were consistently blamed on a single cause: too many people.

In New York’s Times Square, members of the Committee to Defend Biodiversity handed out condoms in colorful packages depicting endangered animals, while a huge and expensive video billboard warned that “human overpopulation is driving species extinct.”

In London’s busiest Underground stations, electronic billboards paid for by Optimum Population Trust declared that 7 billion is “ecologically unsustainable.”

Overpopulation theory spreads

Recently some otherwise responsible scientific groups have joined in promoting the 7 Billion Scare. In April Britain’s Royal Society published a major report calling for action to reduce birth rates in poor countries. More recently, the organization that represents 105 global science academies called on the Rio+20 conference to take “decisive action” to reduce population growth.

Populationist ideas are gaining traction in the environmental movement. A growing number of sincere activists are once again buying into the idea that overpopulation is destroying the earth, and that what’s needed is a radical reduction in birth rates.

Most populationists say they want voluntary birth control programs, but a growing number are calling for compulsory measures. In his best-selling book The World Without Us, liberal journalist Alan Weisman says the only way to save the Earth is to “Limit every human female on Earth capable of bearing children to one.”

Another prominent liberal writer, Chris Hedges, writes, “All efforts to staunch the effects of climate change are not going to work if we do not practice vigorous population control.”

In the recent book Deep Green Resistance, Derrick Jensen and his co-writers argue for direct action by small groups, aimed at destroying industry and agriculture and reducing the world’s human population by 90% or more.

And the famous British naturalist Sir David Attenborough’s tells us that “All environmental problems become harder, and ultimately impossible, to solve with ever more people.”

Attenborough is a patron of Optimum Population Trust, also known as Population Matters, an influential British group that uses environmental arguments to lobby for stopping immigration.

In the United States, groups such as Californians for Population Stabilization, Carrying Capacity Network, and the grossly misnamed Progressives for Immigration Reform do the same, arguing that immigrants are enemies of the environment.

Anti-immigrant organizations in Canada and Australia have adopted the same strategy.

Sadly, we’re hearing the same thing from some people who appear to actually care about the environment, who aren’t just using green arguments to bash immigrants.

For example, William Rees, co-creator of the ecological footprint concept, argues that immigration harms the global environment because immigrants adopt the wasteful lifestyles of the wealthy North. He also says that the money immigrants send home to their families will increase consumption in their home countries and so “contribute to net resource depletion and pollution, both local and global.” In effect, he says that protecting the environment requires potential immigrants to Stay Home and Stay Poor.

I could cite many more examples. Population growth is once again being identified as the primary cause of environmental destruction — and population reduction is being promoted as the solution. Not just by right-wing bigots, but by sincere but confused environmental activists.

While I was writing this talk, the magazine Earth Island Journal was running an online poll on the question “Can you be a good environmentalist and still have children?” The last time I looked, 74% had replied “No.” It’s a small sample, but indicative.

That’s why Simon Butler and I wrote Too Many People? — to provide information and arguments that environmentalists and feminists and socialists can use to respond to the many well-meaning but mistaken activists who have adopted populationist ideas and policies.

I’m not going to repeat all of the arguments in Too Many People? today. If you haven’t read the book, I hope you will do so soon.

Rather I want to offer some historical context, and discuss why the overpopulation argument is so effective and so harmful.

A conservative defense of capitalism

Complaints about overpopulation aren’t new. Writers have been complaining that there are too many people for thousands of years.

But in the modern era, since the French Revolution, the overpopulation argument has played a specific social and ideological role that we don’t find in earlier times.

In good times, the standard capitalist position is that everything is as good as it can be, and everything is getting better. But for over two hundred years, when people protest the system’s massive failures to live up to its promises, the overpopulation argument has been capitalism’s fallback position,

It provides a biological explanation for social problems, allowing the powers that be to shift blame for human problems away from society onto individual behavior. Sure there are problems, but nothing can be done so long as poor people keep having too many babies.

In the 20th century, overpopulation theory had its greatest impact between World War II and the late 1970s.

It began as a response to the revolutionary movements that were then sweeping the Third World, particularly the Chinese revolution of 1949. The revolutionaries blamed capitalism for poverty and hunger, and promoted socialism as the solution.

But if the poverty of India and other countries was actually caused by overpopulation, then Communism could be defeated by birth control. It’s easy to see why that argument appealed to the rich and powerful: it offered a solution that didn’t actually require a change.

As U.S. President Lyndon Johnson expressed it in 1965, “less than $5 invested in population control is worth $100 invested in economic growth.”

That view became the official foreign policy of most wealthy countries. It was implemented directly by northern government aid agencies, and indirectly through massive fertility control projects organized and funded by the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations.

A conservative argument against social environmentalism

In the 1960s and 1970s, while overpopulation theory was being used to explain Third World poverty, it was doing double duty as the explanation for the growing environmental crisis. Once again, it provided an explanation and a solution that did not question capitalism, and that diverted people away from effective solutions.

I should stress here that I am not suggesting that this was a conspiracy to promote capitalism, or that the theorists of overpopulation didn’t believe what they were saying. On the contrary, they were absolutely sincere — they couldn’t imagine any alternative to capitalism, so any remaining problems must be the result of individual human failures.

The first wave of modern environmentalism was triggered by the publication of Rachel Carson’s wonderful book Silent Spring, in 1962.

It’s not widely remembered today, but Carson was a left-wing thinker, and her book focused attention on the crimes of the chemical industry and the complicity of the governments. The principal causes of ecological degradation, Carson insisted, were “the gods of profit and production.”

The chief obstacle to sustainability, she wrote, lay in the fact that we live “in an era dominated by industry, in which the right to make a dollar at any cost is seldom challenged.” (MR Feb 2008)

Carson wasn’t alone in offering that kind of social critique.

In 1962, in Our Synthetic Environment, Murray Bookchin wrote:

“The needs of industrial plants are being placed before man’s need for clean air; the disposal of industrial wastes has gained priority over the community’s need for clean water. The most pernicious laws of the market place are given precedence over the most compelling laws of biology.”

And in 1966, Barry Commoner, who had played a leading role in exposing the dangers of nuclear fallout, argued that environmentally destructive technologies had become “deeply embedded in our economic, social, and political structure.” (Science and Survival)

Carson and Bookchin and Commoner helped initiate a new kind of environmentalism that was rooted in a radical social critique.

Their analysis was rejected by the traditional conservationists, the wealthy organizations and individuals whose primary concern was protecting wilderness areas for tourists and hunters, not overthrowing capitalism or even protecting human welfare.

In 1968, the oldest and richest of the conservation groups, the Sierra Club, financed the publication, promotion and wide distribution of a book that was more agreeable to their pro-capitalist views.

The Population Bomb, by Paul and Anne Ehrlich, skipped over and ignored all the social complexities and critiques offered by Carson and Bookchin and Commoner. It contained not one word about corporations, or industrial policies, or markets.

Instead it explained all environmental destruction with just three words:

“The causal chain of deterioration is easily followed to its source. Too many cars, too many factories, too much detergent, too much pesticide, multiplying contrails, inadequate sewage treatment plants, too little water, too much carbon dioxide—all can be traced easily to too many people.”

The Population Bomb was published in 1968, at the very height of the global radicalization, at a time when millions were questioning capitalism, and when a significant part of their questioning focused on the ongoing and increasing destruction of the natural world.

The Population Bomb was heavily promoted by the Sierra Club, by newspapers and television, and by liberal Democrats who correctly saw it as an alternative to the radical views of Carson, Commoner and Bookchin. It became a huge best-seller— and it played a central role in derailing radical environmentalism.

The impact of Ehrlich’s argument could be seen on the official poster that promoted the first Earth Day in 1970. Its main headline was a sentence from Walt Kelly’s comic strip Pogo — “We have met the enemy and he is us.”That often repeated slogan said, in effect, that the threat to the environment wasn’t corporations, or capitalism or profit — it was people as such.

At a teach-in during that first Earth Day, Barry Commoner strongly challenged Ehrlich’s views. “Pollution,” he said, “begins not in the family bedroom, but in the corporate boardroom.”

He and others carried that argument through the 1970s. Commoner’s 1971 book The Closing Circle is a classic of socialist environmental thought. I recommend it highly.

But the left lost that battle of ideas. In Murray Bookchin’s words:

“Based on my own experience as a very active participant in this momentous period, I can say that if there was any single work that aborted a confluence of radical ideas with public environmental concerns, it was Paul Ehrlich’s Population Bomb. By the early 1970s, Ehrlich’s tract had significantly sidetracked the emerging environmental movement from social critique to a very crude, often odious biologism the impact of which remains with us today.”

The transformation from happened very quickly. By mid-1971 Zero Population Growth, founded and headed by Paul Ehrlich, had some 36,000 members on 400 U.S. campuses, making it by far the largest supposedly progressive organization in the country.

Of course it is impossible to say whether a large-scale anti-capitalist green movement could have been built — but it is very clear that the focus on population diverted the energies of tens of thousands of young greens into harmless channels.

“Green” became synonymous with population control for the third world and personal behavior change in the north. By abandoning the fight for social change, the green movement became powerless and irrelevant.

Decline

In the 1980s, the overpopulation argument seemed to fade away.

In part that was because it was obvious to everyone that Paul Ehrlich’s predictions of massive global famine had not materialized.

And it was clear that even the largest population control programs had had no impact on Third World poverty. Population control simply did not deliver as promised. What’s more, the population control programs financed by U.S. foundations were generating mass resistance: opposition to mass sterilization programs in India played a major role in the 1976 defeat of the government led by Indira Gandhi.

But there was another, deeper cause for the decline of populationism. Put simply, capitalism no longer needed overpopulation theory. The mass radicalization of the 1960s and 1970s was slipping away, and the rise of neoliberalism meant that government intervention in economic and social life, including attempts to control birth rates, was no longer appropriate.

The Reagan government declared that population growth was a non-issue, and slashed spending on family planning programs at home and abroad. George HW Bush, who had advocated global population control programs in the 1970s, reversed himself when he ran for president in 1988. Population reduction was out of style in the ruling class.

The population bombers return

But now the population bombers are back, reflecting the renewed need for a non-radical explanation of the environmental crisis. They aren’t yet as influential was they were in the 60s and 70s, but they are growing, they are being listened to by parts of the ruling class — and most important to us, they are misleading many new green activists.

If we are to win the battle of ideas this time, we need to understand why the overpopulation argument has been so remarkably successful for so long.

One important factor is its power as a weapon of those who seek to provoke division among the oppressed and hatred of those who are “different.” Some of the loudest supporters of populationist policies today are anti-immigrant and racist groups for whom “too many people” is code for “too many foreigners” or “too many non-white people.”

But many activists who honestly want to build a better world and are appalled by the racists of the far right are also attracted to populationist arguments. In Too Many People?, Simon and I argue that three related factors help to explain why the “too many people” explanation is attractive to some environmentalists.

1. Populationism identifies an important issue. Some writers on the left have tried to refute populationism by denying that population growth poses any social, economic, or ecological concerns. Such arguments ignore the fact that human beings require sustenance to live, and that unlike other animals, we don’t just find our means of life, we use the earth’s resources to make them.

There is a direct relationship between the number of people on earth and the amount of food required to sustain them. That’s a fundamental fact of material existence, one that no society can possibly escape. Socialist planning will have to consider population as an important factor in determining what will be produced, and how.

The populationists’ error is not that they see the number of people as important, but that they assume that there is no alternative to society’s present ways of organizing production and distributing products. In the case of food, they assume that the only way to feed the world’s hungry people is to grow more food. Since modern agriculture is ecologically destructive — which it certainly is — feeding more people will cause more destruction, so the only ecologically sound approach is to stop and reverse population growth.

But as we show in Too Many People?, ecologically sound agriculture can produce more than enough food to feed the expected population growth.

In fact, existing food production is more than enough to feed many more people. Just by reducing the food wasted or misused in rich countries to reasonable levels, we could feed billions more people. Or, if population doesn’t grow as much as expected, we could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions by reforesting excess farmland.

But such changes will require global planning for very long-term use, something capitalism cannot do.

One of the major tasks facing a post-capitalist society will be to confront and resolve the gross imbalance that capitalism has created between resources and human needs. And that won’t be a one-time task. The relationship between human needs and the resources and ecological services needed to meet them will constantly change, and so the need to monitor and adjust will be constant as well. We can’t possibly ignore population as a factor in this.

Populationists are right that human numbers must be considered, but they are wrong to blame the imbalance between human needs and resources solely or primarily on human numbers, and they are wrong about the measures needed to solve it

2. Populationism reduces complex social issues to simple numbers. In 1798, Thomas Malthus argued that the imbalance between people and food is a permanent fact of life because population increases geometrically while subsistence only increases arithmetically. He had no evidence for that claim, and history has decisively proven him wrong, but he had shown that appeals to the immutable laws of mathematics can be very effective.

All populationist arguments since then have been rooted in the idea that our numbers determine our fate, that demography is destiny. Hunger, poverty, and environmental destruction are presented as natural laws: surely no reasonable person can argue when the numbers say that population growth is leading us to inevitable disaster.

But even the best population numbers can’t explain the environmental crisis, because quantitative measures can’t take the decisive qualitative issues into account. Knowing the number of people in a city or country tells us nothing about the relationships of gender, race, class, oppression, and power that define our connections with each other and our world.

Dr. Lourdes Arizpe, a founding member of the Mexican Academy of Human Rights and former Assistant Director General of UNESCO, poses the issue very clearly:

“The concept of population as numbers of human bodies is of very limited use in understanding the future of societies in a global context. It is what these bodies do, what they extract and give back to the environment, what use they make of land, trees, and water, and what impact their commerce and industry have on their social and ecological systems that are crucial.”

3. Populationism promises easy solutions. The population explanation seems to offer an easy way out of the world’s problems, without any need for disruptive social change. Simon Ross of Britain’s Optimum Population Trust said exactly that in a recent public statement:

“providing family planning to everyone who wants it is cheap, effective and popular with users. It is ‘low hanging fruit’ and is much easier than many of the techno-fixes and social changes that others are touting around.”

This reminds me of the old joke about a drunk who lost his car keys on First Avenue, but was searching for them on Main Street, “because the light is better here.”

Only major social and economic change can save the earth ― so focusing on “easier” birth rates is just as pointless as searching where the light is good, instead of where the keys are.

One of the things that makes population reduction seem like an easy solution for many advocates is that it puts the burden of action on other people. As the Australian socialist Alan Roberts wrote about the previous wave of populationism, over 30 years ago:

“It was only too evident that when an ecologist, a population theorist or an economist voiced his alarm at the plague of ‘too many people.’ he was not really complaining that there existed too many ecologists. too many population theorists or too many economists: the surplus obviously consisted of less essential categories of the population.”

As Simon and I say in our book, for many populationists, “too many people” is code for too many poor people, too many foreigners, and too many people of color.

Confusing biology and sociology

Because it separates population growth from its historical, social, and economic context, the population explanation boils down to big is bad and bigger is worse, and its solutions are just as simplistic.

Two hundred years ago, the radical essayist William Hazlitt identified the fundamental flaw in Malthus’s theory that population growth made poverty inevitable. Malthus, he wrote, viewed the specific social problems and structures of his time as laws of nature.

“Mr. Malthus wishes to confound the necessary limits of the produce of the earth with the arbitrary and artificial distribution of that produce according to the institutions of society or the caprice of individuals, the laws of God and nature with the laws of man.”

Modern populationists are more likely to justify the “too many people” argument by reference to the laws of thermodynamics than to the laws of God, but Hazlitt’s criticism still applies. Blaming shortages of food and overuse of resources on human numbers confuses sociology with biology: in Hazlitt’s words, it treats the “institutions of society” as “laws of God.”

The capitalist system is grossly inefficient, inequitable, and wasteful. It cannot create without destroying, cannot survive without mindlessly devouring ever more human and natural resources. Populationist responses to environmental problems search for solutions within a system that is inherently hostile to any solution.

Recognition that the system is itself the problem leads to a different approach, the pursuit of an ecological revolution that will refashion the economy and society, restore and maintain the integrity of ecosystems, and improve human welfare.

Capitalism versus nature

In Too Many People?, Simon Butler and I argue that the fundamental cause of environmental destruction is an economy in which the need to reduce costs and increase profits takes precedence over everything else, including human survival.

Universal access to birth control should be a fundamental human right — but it would not have prevented Shell’s massive destruction of ecosystems in the Niger River delta.

It would not have halted or even slowed the immeasurable damage that Chevron has caused to rain forests in Ecuador.

If the birth rate in Iraq or Afghanistan falls to zero, the U.S. military — the world’s worst polluter — will not use one less gallon of oil.

If every African country adopts a one-child policy, energy companies in the U.S., China, Canada and elsewhere will continue burning coal, bringing us ever closer to climate catastrophe.

The too many people argument directs the attention and efforts of sincere activists to programs that will not have any substantial effect on the environment, but can be very harmful to human rights.

It weakens efforts to build an effective global movement against ecological destruction: it divides our forces, by blaming the principal victims of the crisis for problems they did not cause.

Above all, it ignores the massively destructive role of an irrational economic and social system that has gross waste and devastation built into its DNA.

The capitalist system and the power of the 1%, not population size, are the root causes of today’s ecological crisis.

As Barry Commoner said, “Pollution begins not in the family bedroom, but in the corporate boardroom.”

That is the central message of our book.

Unless we transform the economy and our society along sustainable lines, we have no hope of securing a habitable planet, regardless of population levels.

Barry Commoner also said that trying to fix the environment by reducing population is like trying to repair a leaky ship by throwing passengers overboard. Instead we should ask if there isn’t something radically wrong with the ship.

Simon and I have tried to address that question in Too Many People? We hope you find it a useful weapon in the battle of ideas.

I just found this very interesting exchange, and I hope the lack of posts for over a week does not mean an end to the discussion. Another angle on this, I think, is to reverse the causal arrow. The main question debated here has been whether policies, cultural changes, and the like aimed at reducing population are necessary to achieve sustainability or compatible with social justice. Yet, climate scientists have said that the path we are on implies that earth will not be able to support current or projected future human populations. Agricultural productivity could decline by 40%, for instance. If the worst happens, large areas of the earth, such as the Middle East, the American South, and much of Latin America could become literally uninhabitable in that the human body will not be able to stay cool enough to live in prevailing temperatures.

Does anyone believe that the governments of the world will take the drastic actions needed to stabilize emissions and hold temperatures to non-disruptive levels? I don’t. If we stop emissions today, we are already locked in to about a 2C rise. Emissions are increasing. At least 4C is likely by 2100. Exploitation of shale oil, deepwater reserves, and oil sands opens up huge amounts of CO2, so peak oil won’t save us.

Consequently, we have to ask by what process human population will decline, not whether we want to choose to limit or reduce population growth.

John, If I’m reading your comment correctly, you believe that there is no possibility of heading off a climate change catastrophe that will result in the deaths of billions of people.

Climate & Capitalism devoted to promoting and building a global movement to stop capitalist ecocide. If you think that’s a hopeless cause, then you are in the wrong place, and there’s nothing further to discuss.

But maybe you mean that we can head off the catastrophe by reducing population now?

If so, please tell us how you propose to do that. I have studied this subject for years, and I yet to see a concrete proposal for reducing birth rates that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions in time, even under the most optimistic (read: unrealistic) populationist assumptions.

No, I don’t think a crash is inevitable. I am simply noting that things don’t necessarily run from human choices about population to some ecological outcome, namely, a really hot planet. If the climate scientists are correct, continuing on this path will have significant effects on human population, no matter our choices. The outcomes I noted in the first post are from published scientific studies. If the planet becomes x amount hotter, then the following ensues. One prominent climate scientist said that the earth could support no more than one billion people if temperature were to rise the expected 4C. I don’t know how he derived the number, but it’s out there.

I tend to agree with your POV as explained in the article, that ecological effects depend far more on our institutions and policies than on any given population level. We could have a sustainable 7 billion or an unsustainable 3 billion. Given that it becomes a question of whether there is much chance of the world adopting the sustainable, non-catastrophic path. I don’t think the situation is hopeless, but it’s not good. International efforts have produced very little, and the interests (class, primarily) driving policy are firmly entrenched. Nonetheless, if things do get bad enough that ecological limits begin to reduce human population, other choices could become more attractive, even to the powers that be. Indeed, their abiding interest in remaining the powers that be could lead them to move toward wiser choices.

If bad choices prevail, which remains possible, then some scenario toward lower population must be contemplated. I agree that it is unlikely to be humane.

As a postscript, let me note that I came to this issue because I was dissatisfied with some of the more extreme predictions in the left/progressive literature: that climate change means the extinction of the species or the end of civilization. I doubt either is true. We might witness a brutal, chaotic reduction of human population, but the species will survive. Civilization won’t disappear. I’m not even sure capitalism would disappear. But the goal ought to be to ensure that a failed system that brought us to such a pass does go away for good. If we want to ensure that a humane, democratic, egalitarian path is taken, we do need to address the problem as it is, not trying to use over-blown predictions to arouse action.

PS I did buy the book and started reading yesterday.

In the long run, population trumps the economic system. We live on an island with finite resources and it’s unrealistic to suppose that Earth can handle several billion more people than exist today without enormous environmental cost. And I agree with the above posters arguing that the article sets up a false dichotomy. The solutions are inter-connected. Much of the present environmental problems are from first-world over-consumption. Westerners are eating more beef than ever and this is directly related to the high rates of deforestation in tropical countries as forest cover is converted to agriculture. The US population is predicted to swell to 400 million by mid-century, an increase of some 30% from the present 312 million. Most of that growth will come from immigration. If we want to leave any room for any other species, we have to reduce our consumption and support global policies for educating women and giving them access to birth control. I made some other comments about population and the environment here:

http://econowblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/thoughts-on-world-population-day.html

The overpopulation theorists have popularised the “I=PAT” identity: environmental impact = population x affluence x technology.

I always found this perplexingly uninformative. Firstly, as an identity, it’s

a truism. But that’s trivial. Let’s think about it more. If a corporation

develops a new technology – say mobile phones, I remember when they were

new – it rapidly is spread to most of the population by marketing – it’s multiplied.

On the other hand, if a new person is born, they will only add

incrementally to the total stack of people consuming – just one more

mobile phone, not a multiplier.

What this tells us is that you can’t reduce ecological impact to

simplistic equations. Liberal environmentalists routinely tell me that each of the PAT factors is equal. But changes in them do not play out equally. It is more than simple arithmetic.

This is borne out looking at world population trends. The fastest growing populations in the world are largely in Africa – but mostly they are not consumers of high-impact technological commidities (affluence and technology) on any large scale. Their environmental impact is in fact tiny.

If all the populationists like Simon Ross can come up with is an argument about migration from these poor countries to affluent ones, then I would say they have hit rock bottom. That kind of argument is simply an excuse for rich countries not to clean up their act.

In an equitable world, the richest countries should be the most ecologically sustainable. The fact that they aren’t only speaks to their obscene power to get away with murder. Why make excuses and distractions like this population policy?

The survival of people requires necessities of food, water and shelter. Food and shelter requires land and land gets divided more and more as number of people, irrespective of whether they use cell phones or not. The minimum requirement of food and water is same for every human being, no matter where they are situated or what else they consume and whater “ism” or “ity” is operating where they are located.

You can go and check this out yourself but as far as I know, almost every single person in Africa and other developing countries aspires to the standards of living of developed countries [at least in terms of a reasonable security of hygenic food, water, clean air, shelter and health care], you can spend all your time preaching them how good their life is and that they should not worry about adding more children because they are not going to increase their consumption and the land will keep giving them magically even if they grow but it is not going to work unless you live with them and show them that you are enjoying thoroughly their way of living and growing.

It is cruel to the children of Africa and in general all over the world for their parents and other adults who have very little clue how to provide the basics now and in future on a finite earth to keep adding more and more to put them in even greater peril than they already are in. This will go down as the the greatest crime ever in the history of mankind, but only when seen objectively [perhaps by a more intelligent species in future].

Humanity has been very ingeneous in disguising its most basic weakness under fake virtues of “partroitism” [to fight wars for resources, whether local or regional or global] or “God’s will or wish” or blaming squarely on the operating system [whatever ism it is] it has created to hide or postpone the consequences of the weakness.

Piyush2, it would take a book to correct all the errors and misconceptions in your comment.

On food alone: the world produces enough grain alone to provide 3500 calories a day to everyone. Since that’s far more than anyone needs, a rational economic system could feed everyone well, and substantially reduce the area required for agriculture.

World hunger is not caused by “overpopulation” but by a system that treats food as a commodity, not a human right. Food goes where the money is, not to the hungry.

And why don’t people in Africa have enough money to buy food? Why are many African countries net exporters of agricultural products? Might it have something to do with centuries of plunder by the global North? Study after study shows that Northern corporations and governments take far more wealth out of Africa every year than they invest, loan or donate in aid.

And then they (and you) tell the world’s poorest people that their fertility is the problem. It’s called blaming the victims, and it isn’t pretty.

I have heard this lame calorie argument many times before and it is one of the most abused arguments to justify a growing population. The current grain that is produced is using all kinds of industrial agriculture [which by the way is very heavily fossil fuel dependent] and transportation across large distances using fossil fuels. Simply dividing this by number of people simply hides these assumptions of highly unsustainable production. It isn’t yet established that world of 7 billion and counting can be fed without relying on non-renewable fuel and it will not be known until it actually happens, or fails to happen given the precedent of what was happening before fossil fuels.

Carrying capacities vary widely at local scales, currently they are greatly enhanced due to a global transportation network, this is a question mark going forward and there needs to be some humility before making tall claims about food production in the wake of declining fossil fuels and climate change hammering food production. Population growth now needs to be thought through for at least one generation – 70 years, it cannot be justified based on “current” calories showing an excess availability per person. Besides, the calorie number you quote is already reflecting decades of play of capitalism that you are trying to replace.

I am for equity and social justice but I don’t see how these are in conflict with goals of a stable population everywhere, not just in Africa which means population growth needs to stop in US and it applies at an individual level also, only then there can be true justice and equity. Redistributing the wealth [or rather loot from the environment] that has been produced so unsustainably is o.k but it isn’t going to last too long and real wealth, which is the finite ecosystem cannot indefinitely support a growing population, given that we are already so much in overshoot [see Global footprint network].

That “lame calorie argument” originates with three of the world’s leading authorities on the subject, Frances Moore Lappe, Joseph Collins and Peter Rosset of the Institute for Food and Development Policy (Food First).

When I said it would take a book to correct all of your errors and misconceptions on this subject, it was their study I had in mind. If you actually want to understand this issue, rather than simply echoing populationist talking points, I recommend it:

World Hunger: Twelve Myths Grove Press 1998.

I have seen this before, but it does not take away the fundamental arguments I make which is based on the physical reality, not ideology. There needs to be humility on what may be possible on paper with the imagination of the mind and what may actually be possible in practice as we face the crises we face of depleting resources and climate change and hitting several physical limits and considering that time is perhaps the resource in shortest supply and given we are already in signficant overshoot.

You do not have a grounding in reality because you are heavily infused with ideology and hence you fail to evaluate the physical realities and limits with the needed intellect and wisdom. There are many books I can point to in this direction but most likely you have already read them and rejected them because of your ideology. Anyway, based on the responses I have seen so far, I don’t think it is worth the time to write here anymore, this will be my last response here because all I see here is an ideological position that is not grounded in physical reality, and there is no way to argue against that. I wish you all the best in your well-meaning endeavors in future.

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” –John Kenneth Galbraith

“Having no political ideology of which we are aware is not at all the same thing as not having any political ideology. On the contrary, our ‘unaware’ ideology seems to me to be the most potentially influential ideology ….” –Anne Kearney

“Food and shelter requires land and land gets divided more and more as number of people” – abstract arithmetic. How much land is currently available? What is its productivity, now and its potential if better farming methods or different crops are adopted? Unless you can answer questions like these, and match the food production to predicted population growth, you’re not proving anything. Except that population can’t keep growing forever, which uncontroversial (but also irrelevant).

I’ve met poor peasants in a couple of countries. To accuse them of “the greatest crime” is blaming the victim. The rich countries got that way off their colonial exploits where they destroyed, twisted and stunted the economies of poor countries. In fact, millions have been killed in Africa and the rest of the third world, every decade, for the last hundred years or more; by colonial and neo-colonial policy from the rich countries. That will surely go down as “the greatest crime ever in the history of mankind”.

Blaming the victims is all that population theory ever seems to come up with when you draw out the logical conclusions. Repaying the debts of colonialism to poor countries is a much better policy.

Although I never said that, you conveniently associate “the greatest crime..” to poor peasants and to the crime of colonialization, you make that association because that is your way of degrading the arguments, but sane readers can see through this childish fallacy. I say this for anyone anywhere who is making irresponsible decisions on number of children and all policies that encourage population growth in any country, and it does not take away the crime of colonialization. Somehow you and others like Ian use words very strategically like “blaming the victims..” somehow making a connection between anyone who talks about population problem to blaming it on someone else and I see this as dogmatic, as if you all have agreed to repeatedly use it like a weapon on anyone that talks about population. I really have nothing to respond to when I see such childish accusations, it is really degrading of an informed and civil conversation. I feel that those who hold the population argument are somehow seen as evil greedy selfish people instead of coming from a position of compassion, perhaps because they tell a very inconvenient truth.

I grew up in a country that was colonised and then became free and I have seen the culture growing up, I lived in our native village (which was very poor materially) for several months every year and I have that cultural background. Population decisions are largely cultural and religious in nature, not from colonial exploitation. Introduction of vaccines without simultaneous usage of contraception has created a population explosion. Now population pressures have reached a point where women in developing countries desperately want contraception and they shouldn’t be denied that because of ideology. Women in developed countries should also not be denied because of ideology.

Even sustainability has limits. Given that, there will always be a point when the world becomes overpopulated no matter what reforms in the economy take place.

“Feminist reproductive health and justice activists have fought long and hard to liberate family planning from population control.”

That’s true, with the entirely predictable result that, according to the UN 2012 MDG report, “Aid to reproductive health care and family planning remains low.”

Her attack (Common Dreams July 9 http://www.commondreams.org/view/2012/07/09-4) on the recent London Summit on Family Planning, the biggest initiative on family planning in years, shows that she continues to only accept family planning advances on her own idealistic and unrealistic terms. It is entirely appropriate to critique existing programmes but she does not balance that with the practical need to address the plight of the many millions of women who wish to avoid pregnancy but are not using modern contraception.

Family planning is, or should be, a universal right, while smaller families are a universal necessity. That being so, advocating them is not anti-anyone. That does not fit with Betsy’s campaigning agenda, but that does not make them wrong.

Betsy Hartmann’s “idealistic and unrealistic terms” include that women should have the right to choose safe and affordable contraception and abortion, and should not be treated as a means to achieve questionable demographic goals.

She warns that the approach urged by the London Summit cuts across promoting women’s rights: “The assumption is that you can just pour in money and contraceptives to health and family programs that already discriminate against the poor and miraculously they will turn around and help women. Add to this the imperative to drive down birth rates and you get a recipe for coercion.”

What’s more, as she shows, “Even when population programs don’t employ force, they often limit contraceptive choice to long-acting methods like injectables and implants that are viewed as more effective in preventing pregnancy and hence reducing population growth. What is the safest and most appropriate method for the individual woman is simply not the priority.”

She cites research published in The Lancet that using the injectible contraceptive Depo Provera doubles a woman’s chances of acquiring HIV. Guess which contraceptive is heavily promoted by the Gates Foundation, funder of the London Summit?

If raising such concerns is “idealistic and unrealistic” then let’s have much more of it!

Read her article here: https://climateandcapitalism.com/2012/07/11/new-gates-to-coercive-contraception-and-population/

Ian Angus rightfully points out what a dangerous moment we are in, when the environmental movement is at risk of slipping back to the conservative population control paradigm and reproductive rights are threatened by the same agenda.

Feminist reproductive health and justice activists have fought long and hard to liberate family planning from population control. Let us not move backwards to a racist, anti-immigrant, anti-women and ultimately anti-environmental politics.

Read Ian and Simon’s book Too Many People? to get educated on these issues.

Betsy Hartman

Simon Ross writes: “Reducing the birth rate through voluntary measures is one of the most reliable and cost-effective ways of reducing carbon emissions that we know of.”

Really? On what evidence? If that were true, why are most countries in western Europe seeing population decline even as carbon emissions increase? Japan’s population is in rapid decline and yet as its economy grows, so does its impact on the planet.

Population may seem like an easy fix to our ecological crisis, and as Ian writes in his book, obviously there is some correlation between more people and greater resource use. However, to put that as the primary objective or focus on that as social justice activists is completely misplaced – not to mention incredibly dangerous given the long and sordid history of attempts at population control that quickly bleed into coercive methods regardless of their original rationale. (and they will certainly be championed by out-and-out racists and nationalists regardless)

Personally, I don’t need some ulterior motive for supporting reproductive health rights for women. Abortion needs to be free and on demand for any and all reasons – something that faces some of the severest restrictions in the United States, where the practical right to an abortion barely clings to existence. Let’s start fighting for a woman’s right to control her own body as part of a larger movement for women’s equality, not because we want to stop them breeding.

The only population that needs reducing is the global capitalist class intent on wrecking the planet. We definitely do need to get rid of them. They are the ones, a tiny fraction of the world’s population, who are driving us off a cliff. Capitalism must expand – and do so *exponentially* and continuously. Exxon has a turnover larger than 180 countries; it needs to get bigger and it needs to get bigger regardless of whether there are more people in the world, in part by drilling for more oil in ever deeper and more precarious environments. Every other corporation and the states that facilitate their operations need to do the same. If population was stable, it would make absolutely no difference to that equation. In Canada, which is going to overshoot its Kyoto targets by around 30%, is seeing increased emissions not anything remotely to do with population but from tar sands extraction of oil. The single largest polluter in the world is the Pentagon, even as it’s supposedly sailing the “great green fleet”, bombing and murdering its way around the world. If people really want to be environmentally conscious, let’s get together and organize some anti-war demonstrations.

There’s no way around it and there are no short cuts. The problem is the system. It’s not blaming ordinary people in the north for consuming too much -as if we’re the ones making the decisions about what is and what isn’t made or how it gets made, nor racistly blaming poor people-of-color in the South for having too many kids.

The insidiousness of the population argument, as it has always been, is as cover for blaming poor people while letting the people who run the system and the system itself off the hook. Why do you think the over-population argument gets promoted so much and ALWAYS comes up in times of systemic crisis? Because the ruling class likes it! It’s the perfect explanation because it diverts us from setting off to their mansions and corporate lunches with pitchforks.

We can and must fight for regulating corporate and financial power, trimming the worst excesses of capitalism and forcing the governments that we elect to do something for the common people for a change. And we need to do that right now because we need to buy ourselves some time and build our confidence and organization through victories – such as the German mass demonstrations that forced Angela Merkel to abandon nuclear power. But we can’t unite around those themes if we’re focused on population as a significant problem worthy of our attention. Ordinary people are our allies, not our enemies. We need to unite with each other to attack our real enemies, those in the corporate boardrooms of the world. What populationist arguments totally leave out is that people aren’t defined by mindless consumerism or blind desires to copulate and reproduce. We can all think and change our behaviour through collective action and we’re all *producers* as well. We can change the world, but not by blaming each other, building border walls or simply handing out condoms.

But ultimately, we need to get rid of this soul-sucking, life-destroying, planet-wrecking system of capitalism. And, I would argue, replace it with a system based on cooperation, real democracy and production for need not profit that features long-term planning for a sustainable future. That’s what I call socialism. And that’s something worth fighting for.

I have been following the population debate most of my life, and I can assure you that we do not currently know of any way that the +7B people now on this planet can be given a comfortable and meaningful life without adding greatly to the very serious environmental degradation that has already happened just trying to get as far as we have with what we’ve known how to do in the past (recall, for example, that inexpensive solar is only now coming to pass). Certainly we could’ve done better if we’d been smarter, but we’re not, more people will only make the problem harder to solve going forward.

I’m not in favor of coercive population control, which if nothing else does not work, but I am in favor of all manner of economic incentives to ensure that nobody has children without planning it carefully, let alone as a means of securing cheap labor, support once they are too old to work, or for various ideological, religious, or political reasons. This need not be at all contradictory with a socialist agenda; for example universal health care, economic security in old age, and of course women’s equality and education would help enormously.

My problem with this article is that it makes it sound like all “population control” measures are inimical with social justice. There’s room for lots of discussion about which measures are effective enough that they should be implemented even if a significant number of people don’t like them (which is of course always true, or perhaps you think the Catholic church will soon change it’s mind about birth control?), but this article does not even touch upon those issues.

Personally I think if we’re ever going to manage this planet responsibility, at some point we’re going to have to decide how many people can reasonably inhabit it and then not leave what happens to chance. But if that ever happens it will be after my time.

I do think that justice is served by seeking to limit immigration into the “global north”, at least to the same level as emigration, which still means hundreds of thousands each year. We all know that the wealthy western nations are consuming unsustainably, while exploiting and polluting the rest of the planet. Increasing their population by hundreds of thousands year after year after year simply exacerbates that.

I also think that offering a family planning option in the carbon offsetting marketplace is justified. It is a sideshow and I would not overstate it. However, the programme does fund family planning information and services in both developing and developed countries. Reducing the birth rate through voluntary measures is one of the most reliable and cost-effective ways of reducing carbon emissions that we know of.

However, the fundamental strategies of population concern are not migration or offsetting but universal access to family planning, women’s empowerment and the promotion of smaller families as socially responsible. I accept that this is only a reformist programme. However, population concern groups would see this as part of a broader movement towards sustainability, not as a standalone solution.

Whenever we post an article about the fallacies and dangers of populationism, I know for sure that someone will accuse us of making a false dichotomy between population control and social change. “We need to do both,” is the usual line.

This is a variant of the logical fallacy known as the “Argument to Moderation,” the claim that the truth can be found as a compromise between two opposite positions. Liberals and journalists regularly make such claims, because it saves them from actually analyzing and understanding difficult issues.

It’s a regular feature of media reports on climate change: top climate scientist James Hansen says it’s a serious problem, but climate denier and certified loony Christopher Monkton says it isn’t, so the truth must be somewhere in between.

The idea that population control can be merged with a social justice agenda assumes that populationist policies don’t contradict the goal of fundamental social change.

In the case of Simon Ross’s organization, it assumes that you can be for justice while campaigning to block immigrants from your country. It assumes that you can work to end climate change by letting rich polluters “offset” their emissions by paying for birth control in countries whose CO2 emissions are insignificant. (No exaggeration. That’s exactly what his group’s “Pop Offsets” plan does. See https://climateandcapitalism.com/2009/12/28/and-you-thought-carbon-offsets-couldnt-get-worse/)

The reality, as Simon Butler and I show in our book Too Many People? is that population control and social justice are like oil and water. That’s why organizations who say “we need to do both” in practice treat population control as their only priority, with social change deferred to the indefinite future – if indeed it is ever on the agenda.

Solving social justice does not automatically solve population problem and vice versa. Cultures can fully ruin their environment and themselves even with social justice if they cannot control their populations. Cornucopian attitudes are seen today even when people talk about social and environmental justice. 7 billion going to 9 billion? No problem, we have organic farming to the rescue [as if farming before industrial ag wasn’t organic], never mind humanity has used up most of arable land and settled in infertile lands for the food to be shipped long distances using fossil fuels. Does anyone understand the practicalities of settling humanity along with the arable land without reducing it? Do any of these cornucopians understand how climate change is going to hammer those veg gardens and vertical farms? Energy? No problem since we can eat the sun now that we have eaten the battery that was charged by the sun. Never mind the intermittancy [intensified by climate change] and needing to build huge infrastructures to support renewable energy [whose gear all comes from fossil energy]. Collapsing fisheries? Not a problem, we have aquaponics. Never mind the land shared with ag or complex industrial products used to achieve this. How does adding more and more people to the planet that is 150 % into unsustainable terroritory help? Social justice for the sake of social justice is not what I am interested in, it should be a piller towards the goal of sustainability.

You create a false picture by saying that the path followed by “populationists” is either population alone or some mid-point between two mutually exclusive [or opposite?] issues that achieves neither. Obviously there will be specialities as everyone is not the same. If anything, there are hardly any organizations that talk about the population issue openly because of “political correctness”.

On one hand you criticize the “we have found the enemy and they are us” slogan. Then you say population theories assume “other people”, where is the “other” in “we”?. You mix up different organizations differing views/strategies to different issues and put them in a single bucket of people trying to do something about the population problem, as if all these people are in perfect agreement with everyone else in their “ilk”. These tactics will not be fruitful in the end for the change you [we] seek. Most people of reason can see these clearly. It is best not to waste time bashing people who are concerned about population.

Piyush, the ‘we’ is capable of being subtly deflected/manipulated onto the ‘other’ through a tacit racism. The other become good enough to justify elimination through war or underhand means (immigration policies come to be used to justify and legitimate such exclusion/elimination).

Comes a time when people and consumption are needed (on account of economic exigencies), and the commitment to tackle the population problem ‘on a war footing’ is eased (and Sierra Club might go off the activist radar and into ecotrek holidays).

Dominant (read liberal) economic systems/ideologies/lifestyles need not necessarily be emulated for ‘development’ to take place. That it should (only) be so is/has been the master fallacy of Eurocentric science and technology

What I do find interesting in this article is the assumption that somehow a socialist economy will be a radical environmentalist socialist economy by its nature. Somehow I doubt this. I don’t see why the logic of socialist planning lends itself any more naturally to an ecologically sane system of production than a capitalist one. Sure, you don’t have the “profit motive” overriding equity and human rights, but you don’t necessarily have an alternative to “The needs of industrial plants are being placed before man’s need for

clean air; the disposal of industrial wastes has gained priority over

the community’s need for clean water” with socialism. During the heyday of the Soviet Union is when the Aral sea, the fourth largest fresh water body on earth, was sucked dry, for crying out loud. You may end up just having everybody having the SAME shitty air and water.

Well, I’m off to my cabin in the woods…..

You write: “What I do find interesting in this article is the assumption that somehow a socialist economy will be a radical environmentalist socialist economy by its nature.”

Please read again. I said no such thing, nor do I believe it. Capitalism’s need for profit makes sustainability impossible. In a socialist society, it will be possible, but of course not certain.

Here’s what I said in another recent talk:

“some of the worst ecological nightmares of the 20th century occurred in countries that called themselves socialist. We only have to mention the nuclear horror of Chernobyl, or the poisoning and draining of the Aral Sea, to make clear that just eliminating capitalism won’t save the world….

“The lesson we must learn from … from the environmental failures of socialism in the 20th century is that ecology must have a central place in socialist theory, in the socialist program and in the activity of the socialist movement.”

See https://climateandcapitalism.com/2011/10/07/how-to-make-an-ecosocialist-revolution/

“Unless we transform the economy and our society along sustainable lines, we have no hope of securing a habitable planet, regardless of population levels.” Agreed.

Also, unless we address population levels, we have no hope of securing a habitable planet, regardless of whether we transform the economy and our society along sustainable lines. The reason is that there is a direct relationship between the number of people on earth and

the amount of food required to sustain them. That’s a fundamental fact of material existence, one that no society can possibly escape.

It is claimed that ecologically sound agriculture can produce more than enough food to feed the expected population growth. But, right now, agriculture is depleting soil, ground water, fish stocks and habitat, while relying heavily on fossil fuels and energy intensive and polluting fertilizers. That cannot last for ever, while climate change will further reduce agricultural productivity. At the same time, rising living standards in developing countries will create explosive demand for resource intensive meat and dairy diets, in place of the current reliance on more ecologically friendly subsistence crops.

Consequently, it is prudent to seek to reduce by voluntary means family size in all countries and communities, of every class and colour, while simultaneously seeking transformational routes to sustainability.

As much as I agree with the author’s points, ultimately the societies that needs population control the most are like India or Africa isn’t going to care or even understand the ethics of producing babies (religion I’m looking at YOU) they can’t even provide basic needs for or are simply powerless in their attempts to stop the ever rising flood of new people. Effects from overpopulation are gonna get really ugly sooner or later.

Well, I will have to find a copy of your book because the article fails to convince me. I do not see, given the way society is constructed that we can feed, clothe or keep healthy the 7 billion + we have on the planet now, much less any increase. Religion will always stand in the way of population control as it limits the number of victims for it’s insanity and keeping people ignorant is part and parcel of that routine. Just trying to stop polio is being stopped by religious leaders in areas of Pakistan. Maybe you have more facts to support the idea that with more people the problems will solve themselves but history is against you.

Bill, I hope you do read the book, and I look forward to your comments.

We certainly do not suggest that “with more people the problems will solve themselves.” On the contrary, unless we take decisive action to confront the real causes of the problems, we face environmental catastrophe, no matter what happens to birth rates.

As a preview, you can find another reader’s summary of some of our arguments here: http://www.wmtc.ca/2012/06/what-im-reading-marxism-2012-program.html

China’s not that innocent in this field either- didn’t the communist party initiate the one child policy?

Yes. What’s your point?