Jonathan V. Last

Jonathan V. Last

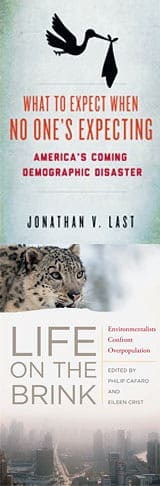

What to Expect When No One’s Expecting:

America’s coming demographic disaster

Encounter Books: New York, 2013

Philip Cafaro and Eileen Crist

Life on the Brink:

Environmentalists confront overpopulation

University of Georgia Press: Athens GA: 2012

reviewed by Ian Angus

In Too many people? Population, immigration, and the environmental crisis (Haymarket, 2011), Simon Butler and I attempted to provide a comprehensive critique of “ideologies that attribute social and ecological ills to human numbers.” In our view, populationism “reduces complex social issues to simple numbers,” and as a result it offers pseudo-solutions that won’t work, while leaving real problems untouched.

While not direct responses, these two books disagree with us, in what seem to be very different ways – one says there aren’t enough people; the other says there are too many. But those superficial differences conceal a common basic approach. They aren’t opposites, they are two extreme forms of 21st century populationism.

* * * * *

What to Expect When No One’s Expecting argues that birth rates are too low to maintain U.S. economic growth. He tells us, without proof of any kind, that “no nation has experienced long-term prosperity in the face of contracting population,” and warns that the U.S. faces “demographic disaster” if white middle class women don’t abandon their selfish anti-children lifestyles, go back to church, stop having abortions, and in general start having more babies. Since he considers such changes unlikely, he reluctantly accepts immigration as the only solution to economic decline — but warns that failure to assimilate immigrants is turning Europe into a “semi-hostile Islamic ummah,” and the same will happen to the U.S. if it doesn’t absolutely reject multiculturalism and insist that newcomers quickly become real Americans.

I suppose it might be possible to write a coherent book defending such views, but this isn’t it. Jonathan Last is too young to remember Leave It To Beaver and Father Knows Best, but that’s the kind of Mom-stays-home-to-raise-kids-while-Dad-goes-to-the-office fantasy world he wants and can never have. Convinced that this spells doom for all that is good, he tosses out population numbers and factoids while ranting that various declining birth rates are “dismal,” “dire,” “ghastly,” a “doomsday scenario” and even “national suicide.”

Last’s real concern is revealed in the quotation he chose to begin his book with – Viktor Orbán, the far-right prime minister of Hungary, warning in 2012 that immigration may ease the economic problems caused by low birth rates, “but it’s not a solution of your real sickness, that you are not able to maintain your own civilization.”

That may win approval from the more racist readers of the neoconservative Weekly Standard, where Last is a senior writer, but it shouldn’t be confused with a serious discussion of population.

* * * * *

On the other side of the populationist coin we find Life on the Brink, an anthology of articles arguing that there are too many people. While there are nuances of difference among them, most of the authors advocate severe immigration restrictions for the U.S., and birth control for everyone in other countries.

The list of contributors is almost a populationist who’s who, ranging from more-or-less liberal environmentalists like Lester Brown, Paul Ehrlich and Robert Engelman to reactionary wilderness cultists like Dave Foreman, Paul Watson and Roderick Nash. Bringing them all together is Philip Cafaro, president of the misnamed Progressives for Immigration Reform (PFIR), an anti-immigrant outfit that’s been described as racism in a fancy green wrapper. It’s disappointing to see even a few genuine environmentalists cooperating with that operation.

Life on the Brink can be read as a compendium of populationist confusion, but be warned: if you have even a touch of human feeling, some of the articles will make you gag.

Roderick Nash, for example, calmly declares that the “first step” towards a sustainable environment “is to check population growth and decrease the human population to a total of about 1.5 billion,” a project that would make China’s infamous one-child policy seem positively benign.

And then there is Paul Watson, who describes humanity as “a deadly autoimmune disease to earth,” and proposes that the disease be managed by preventing poor people from having any babies at all. If only people who prove they “can provide financially and educationally for their offspring” are allowed to procreate, child poverty and overpopulation would soon be eliminated. Bizarrely, he calls that a “humane solution.”

Throughout, it’s clear that these advocates of population reduction are referring to other people – they aren’t complaining that there are too many population theorists, or proposing that rich Americans and tenured professors should return to the countries that their ancestors emigrated from. The disposable people, as the Australian environmentalist Alan Roberts once noted sarcastically, always consist of less essential categories of the population.

The contributors to Life on the Brink write as though the only alternative to their population reduction policies is unlimited capitalist growth, urban spawl, and environmental destruction. In Cafaro’s words, if you aren’t in favor of keeping immigrants out, then you must be in favor of “more cars, more houses, more malls, more power lines, more concrete and asphalt less habitat and fewer resources for wildlife; less water in the rivers and streams for native fish; fewer forests, prairies, and wetlands; fewer wild birds and wild mammals…. You support replacing these other species with human beings ….”

Of course he’s wrong – there is an anti-capitalist, pro-environment alternative to populationism, but you’d never know it from reading Life on the Brink. Cafaro’s one brief mention of the subject appears on the book’s second last page, where he rejects “suggestions from the Left to focus on reforming the economy while ignoring population growth (Angus and Butler 2011)” – not what any reasonable reader would call an accurate summary of our views!

Nor is there any hint that every argument advanced in Life on the Brink has been thoroughly dissected and refuted many times over. That’s not surprising, because the book’s real purpose to give academic credibility and a green gloss to anti-immigrant politics. Any resemblance between this book and genuine environmentalism is strictly cosmetic.

* * * * *

What to Expect and Life on the Brink may seem very different, but they share an ideology that views the number of human beings as more important than how people relate to each other and to the rest of nature. Because they both confuse sociology with biology, they both claim that changing birth rates and head counts would somehow be more effective than (and preferable to) making major changes in our destructive social order.

They aren’t just two sides of the same coin, they are two sides of the same bad penny. Like a bad penny, such ideas frequently turn up, but they don’t improve with repetition.