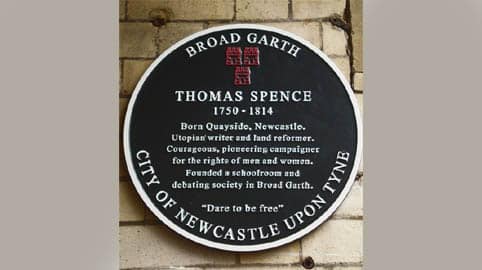

Plaque in Newcastle

Articles in this series:

- Commons and classes before capitalism

- ‘Systematic theft of communal property’

- Against Enclosure: The Commonwealth Men

- Dispossessed: Origins of the Working Class

- Against Enclosure: The commoners fight back

- Thomas Spence on saving the commons

by Ian Angus

Thomas Spence

Thomas Spence (1750-1814) is all but forgotten today, but at the time of the French Revolution he was one of the best-known thinkers and activists in the left-wing of the radical democratic movement in England. In Red Round Globe Hot Burning, Peter Linebaugh describes him as “the most consistent among the common communists of the 1790s.” His influence continued after his death: in 1817, Parliament banned political clubs that supported his views, making Spenceanism the only political ideology ever banned by name in England.

In 1775, outraged by the injustice of Parliamentary enclosures in Yorkshire, he began arguing for common ownership of all land and a decentralized government based on parishes. Over time he extended what came to be called Spence’s Plan, most notably by arguing for universal male and female suffrage. The most complete statement was The Constitution of a Perfect Commonwealth (1798), in which he modified the democratic constitution proposed by the Jacobins in 1793 by adding provisions to ensure that “All men … have a continual property in, and right to the earth and its natural productions.”

A member of the London Corresponding Society, he was repeatedly imprisoned in the 1790s for publishing and selling radical literature, including Tom Paine’s Rights of Man and his own works. In response to Edmund Burke’s reactionary denunciation of “the swinish multitude,” he published a popular magazine, Pig’s Meat, which supported the French Revolution and called for overthrow and expropriation of the British aristocracy. He was strongly critical of Paine and other democrats who supported political equality but not economic equality.

The following are extracts from The End of Oppression (1795), in which Spence replies to a young man’s questions. Once most people favor establishing the Plan, the young man asks, what will be “the most easy method of doing so, and with least bloodshed”?

Spence replies:

In a country so prepared, let us suppose a few thousands of hearty determined fellows well armed and appointed with officers, and having a committee of honest, firm, and intelligent men to act as a provisionary government, and to direct their actions to the proper object.

If this committee published a manifesto or proclamation, directing the people in every parish to take, on receipt thereof, immediate possession of the whole landed property within their district, appointing a committee to take charge of the same, in the name and for the use of the inhabitants; and that every landholder should immediately, on pain of confiscation and imprisonment, deliver to the said parochial committee, all writings and documents relating to their estates, that they might immediately be burnt; and that they should likewise disgorge at the same time into the hands of the said committee, the last payments received from their tenants, in order to create a parochial fund for immediate use, without calling upon the exhausted people.

If this proclamation was generally attended to, the business was settled at once; but if the aristocracy arose to contend the matter, let the people be firm and desperate, destroying them root and branch, and strengthening their hands by the rich confiscations. Thus the war would be carried on at the expense of the wealthy enemy, and the soldiers of liberty beside the hope of sharing in the future felicity of the country, being well paid, would be steady and bold.

And wherever the lands were taken possession of by the people, (which by all means should be as early accomplished as possible) the grand resource of the aristocracy, the rents, would be cut off, which would soon reduce them to reason, and they would become as harmless as other men. …

The good effects of such a change, would be more exhilarating and reviving to the hunger-bitten and despairing children of oppression, than a benign and sudden Spring to the frost-bitten Earth, after a long and severe Winter.

Only think of the many millions of rents that are now paid to those self-created nephews of god almighty, the landed interest, which is literally paid for nothing but to create masters. I say only think of all this money, circulating among the people, and there promoting industry and happiness, and all the arts and callings useful in society; would not the change be unspeakable?

This would neither be a barren revolution of mere unproductive rights, such as many contend for, nor yet a glut of sudden and temporary wealth as if acquired by conquest; but a continual flow of permanent wealth established by a system of truth and justice, and guaranteed by the interest of every man, woman, and child in the nation.

The government also of such a people could no longer be oppressive. The democratic parishes would take care how they suffered their money to be lavished away upon state speculations. And their senators, who could not be men of landed property, would be found to be much more honest and true to the services of their constituents than our now-a-days so much boasted gentlemen of independent fortunes.

When a people create landlords, they create a numerous host of hereditary tyrants and oppressors, who not content with their lordly revenues of rents, seize also upon the government, and parcel it out among themselves, and take as enormous salaries for the places they occupy therein, as if they were poor men; so that the rents which the foolish people foolishly pay for nothing, and the poor dull ass the public, become thus loaded, as it were, with two pair of paniers.

So then, whoever will be so silly good-natured and over-generous as to pay rents to a set of individuals, must not be surprised, if their masters by all ways and means and pretenses should keep them to it, and give scope sufficient to their liberal propensities.

(Spelling and capitalization modernized, paragraph breaks added. The full text of this and other works by Thomas Spence can be found on the Marxist Internet Archive.)