(British Antarctic Survey, October 8, 2008) The amount of plastic washing up onto the shores of remote South Atlantic islands is 10 times greater than it was a decade ago, according to new research published in the journal Current Biology.

Scientists investigating plastics in seas surrounding the remote British Overseas Territories discovered they are invading these unique biologically-rich regions. This includes areas that are established or proposed Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

The study shows for the first time that plastic pollution on some remote South Atlantic beaches is approaching levels seen in industrialized North Atlantic coasts.

During four research cruises on the BAS research ship RRS James Clark Ross between 2013 and 2018, a team of researchers from ten organisations sampled the water surface, water column and seabed, surveyed beaches and examined over 2000 animals across 26 different species.

The amount of plastic reaching these remote regions has increased at all levels, from the shore to the seafloor. More than 90% of beached debris was plastic, and the volume of this debris is the highest recorded in the last decade.

Lead author Dr David Barnes from British Antarctic Survey (BAS) explains:

“Three decades ago these islands, which are some of the most remote on the planet, were near-pristine. Plastic waste has increased a hundred-fold in that time, it is now so common it reaches the seabed. We found it in plankton, throughout the food chain and up to top predators such as seabirds.”

The largest concentration of plastic was found on the beaches. In 2018 we recorded up to 300 items per metre of shoreline on the East Falkland and St Helena – this is ten times higher than recorded a decade ago. Understanding the scale of the problem is the first step towards helping business, industry and society tackle this global environmental issue.

Plastic causes many problems including entanglement, poisoning and starving through ingestion. The arrival of non-indigenous species on floating plastic “rafts” has also been identified as a problem for these remote islands. This study highlights that the impacts of plastic pollution are not only affecting industrialized regions but also remote biodiverse areas, which are established or proposed MPAs.

Andy Schofield, biologist, from the RSPB, who was involved in this research says:

“These islands and the ocean around them are sentinels of our planet’s health. It is heart-breaking watching Albatrosses trying to eat plastic thousands of miles from anywhere. This is a very big wake up call. Inaction threatens not just endangered birds and whale sharks, but the ecosystems many islanders rely on for food supply and health.”

Authors’ summary of “Marine plastics threaten giant Atlantic Marine Protected Areas,”

Current Biology, October 8, 2018.

There has been a recent shift in global perception of plastics in the environment, resulting in a call for greater action. Science and the popular media have highlighted plastic as an increasing stressor. Efforts have been made to confer protected status to some remote locations, forming some of the world’s largest Marine Protected Areas, including several UK overseas territories.

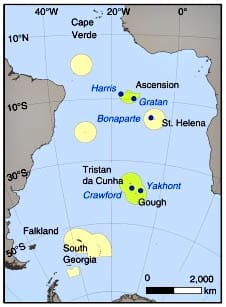

We assessed plastic at these remote Atlantic Marine Protected Areas, surveying the shore, sea surface, water column and seabed, and found drastic changes from 2013–2018. Working from the RRS James Clark Ross at Ascension, St. Helena, Tristan da Cunha, Gough and the Falkland Islands, we showed that marine debris on beaches has increased more than 10 fold in the past decade. Sea surface plastics have also increased, with in-water plastics occurring at densities of 0.1 items m–3; plastics on seabeds were observed at ≤ 0.01 items m–2.

For the first time, beach densities of plastics at remote South Atlantic sites approached those at industrialized North Atlantic sites. This increase even occurs hundreds of meters down on seamounts. We also investigated plastic incidence in 2,243 animals (comprising 26 species) across remote South Atlantic oceanic food webs, ranging from plankton to seabirds. We found that plastics had been ingested by primary consumers (zooplankton) to top predators (seabirds) at high rates. These findings suggest that MPA status will not mitigate the threat of plastic proliferation to this rich, unique and threatened biodiversity.