Some Canadian environmentalists are blaming this ecological nightmare on foreign investors. Their analysis is both mistaken and dangerous: the tar sands are firmly in Canadian hands, and those hands are very dirty.

THE TAR SANDS: A MADE-IN-CANADA PROBLEM

by Paul Kellogg

PolEcon.net, January 4, 2013

© 2013 Paul Kellogg, published with permission.

Paul Kellogg is a teacher, researcher and writer at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies, Athabasca University, Alberta, Canada. His focus is political economy (international and Canadian), globalization and social movements.

The tar sands development in northern Alberta is an ecological nightmare, and an insult to indigenous land rights. This nightmare and this insult are profoundly Canadian – shaped by Canadian corporations and Canadian government policies. Unfortunately, there has been a tendency by some in the movement to try and “off-shore” the problem, shifting the blame, in particular to China. This has no basis in fact, and opens the door to a nasty politics of xenophobia.

Listen to the rhetoric. Elizabeth May, leader of the Green Party, rightly highlighted concerns about a trade deal between Canada and China. But she irresponsibly raised the stakes, saying that, as a result of the deal, Canada would “become the resources colony in that context” (Scoffield, 2012).

Nikki Skuce from B.C.-based ForestEthics Advocacy, in a report on the tar sands that is receiving wide circulation, similarly argued that “Canada is about to move one step closer to being a resource colony for China” (2012a). She bases this claim on the assertion that “the vast majority of tar sands production is not owned by Canadians,” and focuses on the growing role of “rising Chinese Investment”. The combination, she says, is “positioning Canada as China’s resource colony” (Skuce, 2012b).

May and Skuce are quite wrong. Targeting an Asian country as “the problem” should set off alarm bells – particularly when that targeting takes place in British Columbia, a province with a noxious history of “yellow peril” politics. China might be undergoing a massive industrial revolution, but it remains a society far more impoverished than Canada.

More seriously, the term “colony” should not be used lightly. It is a very heavy term, loaded with meaning. For China in the 19th century, the encounter with European colonialism, meant the horrors of the Opium War (1839-1842), the Arrow War (1856-1858, sometimes called the Second Opium War), the resulting disintegration of social order in the 1850s and 1860s, and the subsequent carving up of various ports into “concessions” open to the imperialist powers (Dillon, 2010, pp. 29–119).

There is a colonial history in Canada in the same century, but it is not a story about Canada’s subjection by non-Canadians. It is rather a story of colonial violence, carried out by the newly created Canadian state, directed against the Cree, Assiniboine, Métis and other peoples, as Canada used force to consolidate its developing capitalist economy (Ryerson, 1975, pp. 309–423). Canada is not a victim of colonialism, but is rather a colonial power in its own right.

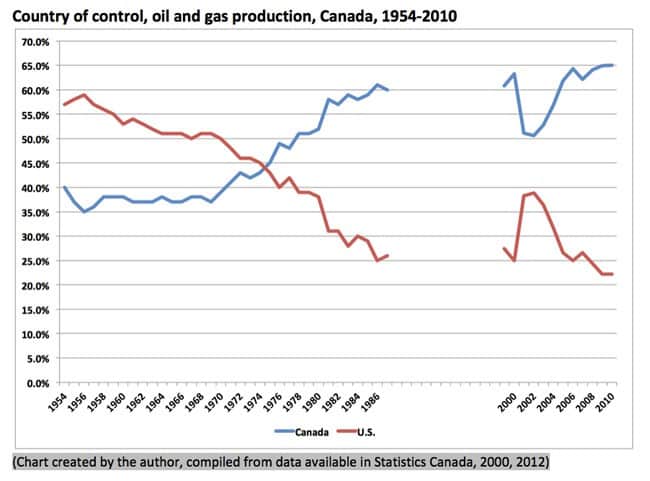

Further, this alarmism about Canada becoming anyone’s resource colony has no basis in fact. Statistics Canada has systematically collected data on all sorts of aspects of “who controls what” in the Canadian economy, going back decades. For oil and gas, we have access to two separate databases. One is from 1954 until 1986 (based on percentage of capital employed in petroleum and natural gas), and the other is from 2000 until 2010 (based on percentage of assets in oil and gas extraction and support activities).

The story told by these statistics is quite straightforward: Canadian control of the oil and gas industry is steadily increasing.

Go back 60 years, and control of the oil and gas sector was in its majority held outside of Canada – principally by corporations and individuals based in the United States. Through the decades of the 1950s and 1960s, in any given year, typically less than 40 per cent was in the hands of Canadians, with U.S. control at times approaching 60 per cent.

This steadily changed through the 1970s and 1980s. By 1986, the year the first database ends, the situation had reversed, Canadian control sitting at about 60 per cent, U.S. control at below 30 per cent.

When we pick up the story with the new database series, beginning in 2000, the pattern continues. By 2010, Canadian control of the oil and gas industry was approaching the two-thirds mark, while U.S. control was down to just above 20 per cent.

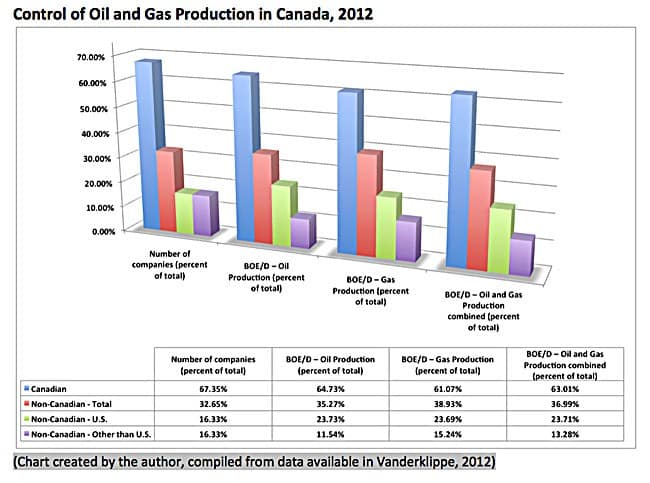

There are other ways by which to measure control of oil and gas production in Canada. Calgary-based Peters & Co. has developed a database for country of control in the oil and gas industry based on the 50 biggest companies in the field, as measured by 2012 production of Barrels of Oil Equivalent per Day (BOE/D).

The next chart takes their figures, their four categories (number of companies, oil production, gas production and then oil and gas production combined) and then divides the universe of companies into four categories – Canadian, non-Canadian (total), non-Canadian (U.S.) and non-Canadian (other than U.S.).

The results provide a momentary, one-year snapshot, perfectly consistent with the 66-year Statistics Canada time series, highlighted above. In all four categories, Canadian control is above 60 per cent, and sometimes close to 70 per cent.

Peters & Co. would suggest that the Canadian figures depicted here are just a bit too high. Their statisticians decided that the third biggest company on the list – Husky Energy Inc. – should be classified as “non-Canadian”. As Husky is responsible for 314,000 out of the daily total of 5,107,000 BOE/D, this would reduce the Canadian control figures above by about six per cent.

This is a very arbitrary classification. It is true that Husky, although headquartered in Calgary, does have 70% of its shares held offshore in companies based in Barbados and Luxemburg. However, those companies are in turn controlled by a man called Li Ka-shing and his family (Husky Energy, 2012, p. 4). Li Ka-shing was born in China, but according to the Globe and Mail, is also a Canadian citizen (MacKinnon, 2011). If he is a dual citizen, Chinese and Canadian, it is not surprising that this is a fact about which he is fairly circumspect. China does not recognize dual citizenship, and Li Ka-shing has substantial holdings in China. Frequently referred to in the press as a “Hong Kong billionaire”, in 2000 “his two main companies, Hutchison Whampoa Ltd. … and property developer Cheung Kong (Holdings) Ltd.” accounted for “about 15% of the market capitalization of Hong Kong Stock Exchange’s main board” (Cattaneo, 2000). But this corporate empire – including Husky – is in large part managed by Li Ka-shing’s two sons, Victor and Richard Li, both of whom are absolutely Canadian citizens (York, 2005).

So Canadian are these two, that they ranked a mention in 2003 as two of the three new additions to Canadian Business’s annual list of Canada’s richest individuals (Erwin, 2003).

In other words, the family which controls Husky Energy has some pretty good credentials as being Canadian, as Canadian as many of the other estimated 2.8 million Canadian citizens who some of the time live outside the country (Hoffman, 2010). When Céline Dion sings, Wayne Gretzky plays hockey, or Justin Bieber breaks hearts, we don’t question their Canadian bona fides.

ForestEthics Advocacy uses a different method by which to assert minority Canadian control in the tar sands. They argue it is misleading to call companies Canadian just because they have headquarters in Canada. The key is to examine the nationality of those who own their shares, and since “71 per cent of all tar sands production is owned by non-Canadian shareholders” it is justifiable to deny that what is going on in the tar sands is made in Canada.

Certainly having a head office in Canada is not sufficient as proof of Canadian control. Imperial Oil, the sixth biggest oil and gas producer in Canada, proclaims its head office as being in Calgary, but also indicates, in the same source, that it is 70 per cent owned by Exxon Mobil Corporation, the pre-eminent U.S.-based oil multinational (Imperial Oil, 2012, p. 32 and 29). No one argues that Imperial Oil should be considered as being under Canadian control, any more than anyone would make a similar argument about several others on the list, including Statoil Canada, owned by Statoil Norway and Murphy Oil Corp., headquartered in El Dorado Arkansas (Bloomberg BusinessWeek, 2012; Murphy Oil Corporation, 2012, p. 1).

But ForestEthics goes further, claiming that we should also exclude from the Canadian list: the biggest oil and gas producers in Canada, Canadian Natural Resources Ltd.; the second biggest, Suncor Energy Inc.; the seventh biggest, Cenovus Energy Inc.; the 13th biggest, Canadian Oil Sands; and the 33rd biggest, MEG Energy Corp. (Skuce, 2012b) These companies, they argue, have more than 50% of their shares owned outside of Canada, and are therefore not really Canadian.

Look at the four biggest corporations on the list. Canadian Natural Resources, Suncor, Cenovus, and Canadian Oil Sands are all headquartered in Calgary. None of them are subsidiaries of another corporation (Canadian Natural, 2012; Canadian Oil Sands, 2012; Cenovus, 2012; Suncor, 2012). To say they are “foreign controlled” because slightly more than 50% of their shares are held by people living outside of Canada, displays a misunderstanding of the way in which corporate control is exercised in a capitalist economy.

According to a very standard understanding of corporate power, provided by the Organization for Cooperation and Economic Development (OECD), “control of a corporation occurs when a single institutional unit owning more than a half of the shares, or equity, of a corporation is able to control its policy” (2003). In other words, identifying that 50% of the shares of a corporation are owned outside of Canada, would only be significant if those shares were controlled by a single entity.

The OECD goes further. “In practice, when ownership of shares is widely diffused among a large number of shareholders, control may be secured by owning 20 per cent or less of total shares.” This is actually fairly basic economics. ForestEthics Advocacy’s “resource colony of China” paradigm is based on a flawed understanding of the way in which control is exercised in the real world of contemporary capitalism.

Maude Barlow, National Chairperson of the Council of Canadians, speaking November 17, 2012 to a packed Toronto teach-in on the pipelines, also mistakenly asserted that “more than two-thirds of the tar sands production is now in foreign hands”. But Barlow is aware of the fact that the tar sands problem cannot be blamed on non-Canadians. She immediately qualified her statement, saying this “doesn’t mean that it would be fine if it was in Canadian hands” (LeftStreamed, 2012).

Our movement needs to be completely clear – the tar sands are in Canadian hands, and those hands are dirty.

Appendix – Top Oil and Gas Producers in Canada, September 2012

| Country Base | Company | Production (BOE/D) |

| Canada | Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. (1) | 546,000 |

| Canada | Suncor Energy Inc. (2) | 470,000 |

| Canada-China | Husky Energy Inc. (3) | 314,000 |

| U.K. | Shell Canada Ltd. (4) | 297,000 |

| U.S. | ConocoPhilips Canada Resources Corp. (5) | 291,000 |

| U.S. | Imperial Oil Ltd. (6) | 277,000 |

| Canada | Cenovus Energy Inc. (7) | 255,000 |

| Canada | Encana Corp. (8) | 247,000 |

| U.S. | Devon Canada Corp. (9) | 216,000 |

| Canada | Penn West Petroleum Ltd. (10) | 166,000 |

| U.S. | Apache Canada Ltd. (11) | 135,000 |

| Canada | Pengrowth Energy Corp. (12) | 120,000 |

| Canada | Canadian Oil Sands Ltd. (13) | 106,000 |

| Canada | Crescent Point Energy Corp. (14) | 106,000 |

| Canada | Talisman Energy Inc. (15) | 105,000 |

(Table created by the author, compiled from data available in Vanderklippe, 2012)

This article is based on research which will be presented in more detail as a chapter in Meenal Shrivastava and Lorna Stefanick, eds., Beyond the Rhetoric: Democracy and Governance in a Global North Oil Economy. Edmonton, AthabascaUniversity Press

References

Bloomberg BusinessWeek (2012, December 27) Statoil Canada Ltd.: Private Company Information [online]. Businessweek.com. Available from: http://investing.businessweek.com/research/stocks/private/snapshot.asp?privcapId=24402363 [Accessed 27 December 2012 ]

Canadian Natural (2012) 2011 Annual Report [online]. Calgary: Canadian Natural Resources Limited. Retrieved from http://www.cnrl.com/investor-information/financial-information/financial-reports/annual-report.html

Canadian Oil Sands (2012) 2011 Annual Report [online]. Calgary: Canadian Oil Sands Limited. Retrieved from http://www.cdnoilsands.com/investor-centre/Financial-Reports-and-Filings/annual-reports/default.aspx

Cattaneo, C. (2000, October 30) ‘Lau details Husky’s plan for growth’, National Post, C1.

Cenovus (2012) 2011 Annual Report [online]. Calgary: Cenovus Energy. Retrieved from http://www.cenovus.com/invest/financial-information/annual-reports.html

Dillon, M. (2010) China: A Modern History, Reprint. New York: I. B. Tauris.

Erwin, S. (2003, December 9) ‘Thomsons top Canada’s rich list’, Kingston Whig – Standard, 36.

Hoffman, A. (2010, July 31) ‘A Canadian key drives a Chinese success’, The Globe and Mail, B4.

Husky Energy (2012) Management Information Circular [online]. Calgary: Husky Energy. Retrieved from http://www.huskyenergy.com/investorrelations/annualreports.asp

Imperial Oil (2012) 2011 Summary Annual Report [online]. Calgary: Imperial Oil Limited. Retrieved from http://www.imperialoil.ca/Canada-English/about_investors_reports_aandq.aspx

LeftStreamed (2012) Tar Sands Come to Ontario – No Line 9! [5/5] [online]. Toronto. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9cATCLbEIiA&feature=youtube_gdata_player

MacKinnon, M. (2011, October 31) ‘China test drives the concept of charity’, The Globe and Mail, A3.

Murphy Oil Corporation (2012) 2011 Annual Report [online]. El Dorado, Arkansas: Murphy Oil Corporation. Retrieved from http://www.murphyoilcorp.com/ir/reports.aspx

OECD (2003, March 3) Control of a corporation [online]. OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms. Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=445 [Accessed27 December 2012

Ryerson, S. B. (1975) Unequal union: confederation and the roots of conflict in the Canadas, 1815-1873. Toronto: Progress Publishers.

Scoffield, H. (2012, October 30) ‘Investment deal with China would leave Canada a resource colony: opponents’, Whitehorse Star, 8.

Skuce, N. (2012a, October 24) ‘It’s a bad deal’, The Globe and Mail, A14.

Skuce, N. (2012b) Who Benefits? An investigation of foreign investment in tar sands [online]. ForestEthics Advocacy. Retrieved from http://www.forestethics.org/news/who-benefits-investigation-foreign-investment-tar-sands

Statistics Canada (2000) CANSIM Table 3760047 – International investment position, capital employed in non-financial industries by country of ownership, annually. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada (2012) CANSIM Table 1790004 – Corporations Returns Act (CRA), major financial variables, annually. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Suncor (2012) 2011 Annual Report [online]. Calgary: Suncor Energy Inc. Retrieved from http://www.suncor.com/en/investor/3342.aspx

Vanderklippe, N. (2012, December 12) ‘How much of Canada’s energy resource lies in foreign hands?’, The Globe and Mail, B4.

York, G. (2005, November 29) ‘Canadians by choice, Hong Kongers by nature’, The Globe and Mail, H4.