The next time someone claims that global warming has “stopped,” show them this response from the actual climate scientists at the UK Met Office

Global warming goes on

(UK Meteorological Office, 23 September 2008)

Anyone who thinks global warming has stopped has their head in the sand.

The evidence is clear – the long-term trend in global temperatures is rising, and humans are largely responsible for this rise. Global warming does not mean that each year will be warmer than the last, natural phenomena will mean that some years will be much warmer and others cooler. You only need to look at 1998 to see a record-breaking warm year caused by a very strong El Niño. In the last couple of years, the underlying warming is partially masked caused by a strong La Niña. Despite this, 11 of the last 13 years are the warmest ever recorded.

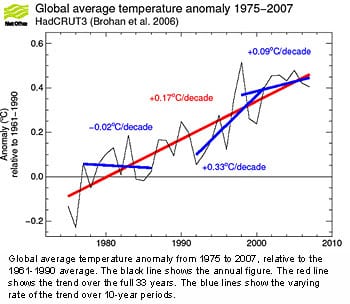

Average global temperatures are now some 0.75 °C warmer than they were 100 years ago. Since the mid-1970s, the increase in temperature has averaged more than 0.15 °C per decade. This rate of change is very unusual in the context of past changes and much more rapid than the warming at the end of the last ice age. Sea-surface temperatures have warmed slightly less than the global average whilst temperatures over land have warmed at a faster rate of almost 0.3 °C per decade.

Over the last ten years, global temperatures have warmed more slowly than the long-term trend. But this does not mean that global warming has slowed down or even stopped. It is entirely consistent with our understanding of natural fluctuations of the climate within a trend of continued long-term warming.

These natural fluctuations include the El Niño Southern Oscillations (ENSO) in the Pacific Ocean. In El Niño years – those when cold surface water is not apparent in the tropical eastern Pacific – global temperature is considerably warmer than normal. A particularly strong El Niño occurred in 1998 resulting in the warmest year on record across the globe. In La Niña years – when cold water rises to the surface of the Pacific Ocean – temperatures can be considerably colder than normal. Volcanic eruptions can also cause temporary drops in global temperatures because of huge amounts of dust thrown high into the atmosphere that reduce the amount of sunlight that reaches the surface. A La Nina was present throughout 2007 and much of 2008; — despite this temporary cooling, 2008 is still likely to be the seventh warmest on the global record.

As a result of such fluctuations, global average temperature trends calculated over ten-year periods have varied since the mid-1970s, from a modest cooling to a warming rate of more than 0.3 °C per decade. Similar behaviour is also seen in individual model predictions of future climate change where the long-term warming trend is forecast to exceed 2 °C per century. Even then, due to the natural variations in climate, we expect to see ten-year periods both globally and regionally with little or no warming and other ten-year periods with very rapid warming. This complex behaviour of the climate system shows why we need to examine much longer periods than ten years if we are to fully understand and quantify how the climate is changing.

These longer-term analyses have shown that current warming is being caused mainly by human emissions of greenhouse gases which have accumulated in the atmosphere and intensified the greenhouse effect by absorbing more of the thermal radiation emitted by the land and ocean. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded in its most recent assessment in 2007 that increases in man-made greenhouse gas concentrations have ‘very likely’ caused most of the overall increase in global average temperatures since the mid 20th century.

This long-term warming trend is set to continue as the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere continues to increase. Inevitably this will lead to further impacts on our lives and the world’s natural ecosystems. Heatwaves and droughts are likely to become more prevalent; snow cover is projected to continue to diminish; and sea ice to continue to shrink. On shorter timescales natural climate variations and other factors, like volcanoes, will continue to temporarily enhance or reduce the magnitude and impacts of these longer-term changes.

Predictions of future conditions, such as the seasonal, decadal and centennial forecasts provided by the Met Office, can help considerably in dealing with the challenges of our changing climate. For example, the emerging science of decadal forecasting has exciting potential to provide water companies, emergency responders and local authorities with information that can help them in planning for future droughts and floods.