The extreme heatwaves of 2023, which fueled huge wildfires and severe droughts, also undermined the land’s capacity to soak up atmospheric carbon. This diminished carbon uptake drove atmospheric carbon dioxide levels to new highs, intensifying concerns about accelerating climate change.

Measurements from Hawaii’s Mauna Loa Observatory showed that atmospheric carbon concentrations surged by 86% in 2023 compared to the previous year, marking a record high since tracking began in 1958. Despite this sharp increase, fossil fuel emissions only rose by about 0.6%, suggesting that other factors, such as weakened carbon absorption by natural ecosystems, may have driven the spike.

Typically, land absorbs roughly one-third of human-generated carbon dioxide emissions. However, research published in National Science Review on October 22 reveals that in 2023, this capacity fell to just one-fifth of its usual level, marking the weakest land carbon sink performance in two decades.

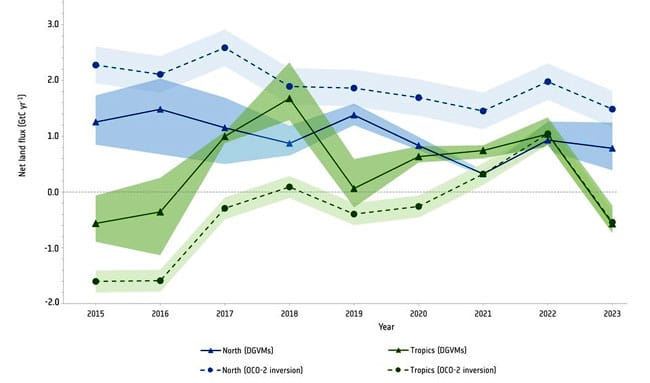

Changes in the declining northern land carbon sink (blue) and the variations of tropical land flux (green) for 2015–2023. The solid lines reflect analyses using dynamic global vegetation models while the dotted lines are based on data from NASA–JPL’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 mission.

Philippe Ciais, from France’s Laboratory for Climate and Environmental Sciences, explained,

“Our research shows that 30% of this decline was driven by the extreme heat of 2023, which fueled massive wildfires that ravaged vast areas of Canadian forest and triggered severe drought across parts of the Amazon rainforest. These fires and droughts led to substantial vegetation loss, weakening the land ecosystem’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide. This was further compounded by a particularly strong El Niño, which historically reduces the carbon absorption capacity in the Tropics.”

Widespread wildfires across Canada and droughts in the Amazon in 2023 released about the same amount of carbon to the atmosphere as North America’s total fossil fuel emissions, underscoring the severe impact of climate change on natural ecosystems.

The Amazon – one of the world’s most crucial carbon sinks – is showing signs of long-term strain, with some regions shifting from absorbing carbon to becoming net sources of carbon emissions.

The researchers suggest that the declining capacity of Earth’s land ecosystems to absorb carbon dioxide may indicate that these natural carbon sinks are nearing their limits and no longer able to provide the mitigation service they have historically offered by absorbing half of human-induced carbon dioxide emissions.

Current climate models might be underestimating the rapid pace and impact of extreme events, such as droughts and fires, on the degradation of these crucial carbon reservoirs, so achieving safe global warming limits will require even more ambitious emission reductions than previously anticipated.

Clement Albergel of the European Space Agency described the results as “particularly alarming, especially considering the difficulty the world is having limiting warming to 1.5°C, as laid out in the Paris Agreement.”

Adapted from materials provided by the European Space Agency