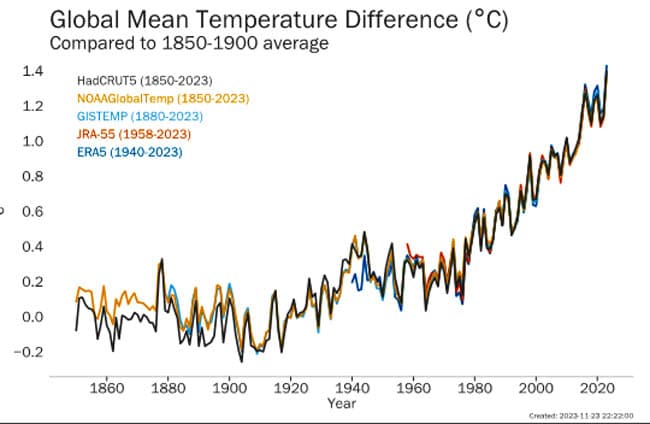

The World Meteorological Organization’s provisional State of the Global Climate report confirms that 2023 will be the warmest year on record. Data until the end of October shows that the year was about 1.40 degrees Celsius (with a margin of uncertainty of ±0.12°C ) above the pre-industrial 1850-1900 baseline. The difference between 2023 and 2016 and 2020 — which were previously ranked as the warmest years — is such that the final two months are very unlikely to affect the ranking.

The past nine years, 2015 to 2023, were the warmest on record. The warming El Niño event, which emerged during the Northern Hemisphere spring of 2023 and developed rapidly during summer, is likely to further fuel the heat in 2024 because El Niño typically has the greatest impact on global temperatures after it peaks.

Greenhouse gas levels are record high. Global temperatures are record high. Sea level rise is record high. Antarctic sea ice is record low. “It’s a deafening cacophony of broken records,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas.

“These are more than just statistics. We risk losing the race to save our glaciers and to rein in sea level rise. We cannot return to the climate of the 20th century, but we must act now to limit the risks of an increasingly inhospitable climate in this and the coming centuries. Extreme weather is destroying lives and livelihoods on a daily basis — underlining the imperative need to ensure that everyone is protected by early warning services.”

Carbon dioxide levels are 50 % higher than the pre-industrial era, trapping heat in the atmosphere. The long lifetime of CO2 means that temperatures will continue to rise for many years to come.

The rate of sea level rise from 2013-2022 is more than twice the rate of the first decade of the satellite record (1993-2002) because of continued ocean warming and melting of glaciers and ice sheets.

The maximum Antarctic sea-ice extent for the year was the lowest on record, a full 1 million km2 (more than the size of France and Germany combined) less than the previous record low, at the end of southern hemisphere winter. Glaciers in North America and Europe once again suffered an extreme melt season. Swiss glaciers have lost about 10 percent of their remaining volume in the past two years, according to the WMO report.

“This year we have seen communities around the world pounded by fires, floods and searing temperatures. Record global heat should send shivers down the spines of world leaders,” said United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres.

The WMO provisional State of the Global Climate report was published to inform negotiations at COP28 in Dubai. It combines input from National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, regional climate centers, UN partners and leading climate scientists. The temperature figures are a consolidation of six leading international datasets.

The final State of the Global Climate 2023 report, along with regional reports, will be published in the first half of 2024.

Greenhouse Gases: Observed concentrations of the three main greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide – reached record high levels in 2022, the latest year for which consolidated global values are available. Real-time data from specific locations show that levels of the three greenhouse gases continued to increase in 2023.

Global Temperatures: The global mean near-surface temperature in 2023 (to October) was around 1.40 (± 0.12) °C above the 1850–1900 average. Based on the data to October, it is virtually certain that 2023 will be the warmest year in the 174-year observational record, surpassing the previous joint warmest years, 2016 at 1.29 ( ± 0.12) °C above the 1850–1900 average and 2020 at 1.27 (±0.13) °C.

Record monthly global temperatures have been observed for the ocean – from April through to October — and, starting slightly later, the land — from July through to October, June, July, August, September and October 2023 each surpassed the previous record for the respective month by a wide margin in all datasets used by WMO for the climate report. July is typically the warmest month of the year globally, and thus July 2023 became the all-time warmest month on record.

Sea surface temperatures: Global average sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) were at a record observed high for the time of year, starting in the late Northern Hemisphere spring. April through September (the latest month for which we have data) were all at a record warm high, and the records for July, August and September were each broken by a large margin (around 0.21 to 0.27 °C). Exceptional warmth was recorded in the eastern North Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, and large areas of the Southern Ocean, with widespread marine heatwaves.

Ocean heat content: Ocean heat content reached its highest level in 2022, the latest available full year of data in the 65-year observational record.-It is expected that warming will continue — a change which is irreversible on centennial to millennial timescales. All data sets agree that ocean warming rates show a particularly strong increase in the past two decades.

Sea level rise: In 2023, global mean sea level reached a record high in the satellite record (since 1993), reflecting continued ocean warming as well as the melting of glaciers and ice sheets. The rate of global mean sea level rise in the past ten years (2013–2022) is more than twice the rate of sea level rise in the first decade of the satellite record (1993–2002).

Cryosphere: Antarctic sea-ice extent reached an absolute record low for the satellite era (1979 to present) in February. Ice extent was at a record low for the time of year from June onwards. The annual maximum in September was 16.96 million km2, roughly 1.5 million km2 below the 1991–2020 average and 1 million km2 below the previous record low maximum, from 1986.

Arctic sea-ice extent remained well below normal, with the annual maximum and minimum sea ice extents being the fifth and sixth lowest on record respectively.

Glaciers in western North America and the European Alps experienced an extreme melt season. In Switzerland, glaciers have lost around 10% of their remaining volume in the past two years.

Extreme weather and climate events: Extreme weather and climate events had major impacts on all inhabited continents. These included major floods, tropical cyclones, extreme heat and drought, and associated wildfires, leaving a trail of devastation and despair around the world.

Flooding associated with extreme rainfall from Mediterranean Cyclone Daniel affected Greece, Bulgaria, Türkiye, and Libya with particularly heavy loss of life in Libya in September.

Tropical Cyclone Freddy in February and March was one of the world’s longest-lived tropical cyclones with major impacts on Madagascar, Mozambique and Malawi. Tropical Cyclone Mocha, in May, was one of the most intense cyclones ever observed in the Bay of Bengal.

Extreme heat affected many parts of the world. Some of the most significant were in southern Europe and North Africa, especially in the second half of July where severe and exceptionally persistent heat occurred. Temperatures in Italy reached 48.2 °C, and record-high temperatures were reported in Tunis (Tunisia) 49.0 °C, Agadir (Morocco) 50.4 °C and Algiers (Algeria) 49.2 °C.

Canada’s wildfire season was well beyond any previously recorded. The total area burned nationally as of 15 October was 18.5 million hectares, more than six times the 10-year average (2013–2022). The fires also led to severe smoke pollution, particularly in the heavily populated areas of eastern Canada and the north-eastern United States. The deadliest single wildfire of the year was in Hawaii, with at least 99 deaths reported — the deadliest wildfire in the USA for more than 100 years.

Five consecutive seasons of drought in the Greater Horn of Africa was followed by floods, triggering even more displacements. The drought reduced the capacity of the soil to absorb water, which increased flood risk when the Gu rains arrived in April and May

Long-term drought intensified in many parts of Central America and South America. In northern Argentina and Uruguay, rainfall from January to August was 20 to 50% below average, leading to crop losses and low water storage levels.

Socio-economic impacts: Extreme weather and climate events interact with and in some cases trigger or exacerbate situations concerning water and food security, population mobility and environmental degradation.

The number of people who are acutely food insecure has more than doubled, from 135 million people before the COVID-19 pandemic to 345 million people in 2023 (in 53 monitored countries). Global hunger levels remained unchanged from 2021 to 2022. However, these are still far above pre-COVID 19 pandemic levels: in 2022, 9.2% of the global population (735.1 million people) were undernourished, compared to 7.9% of the population (612.8 million people) in 2019. The current global food and nutrition crisis is the largest in modern human history.

Globally, annual economic losses from climate and weather-related disasters have significantly increased since the 2000s. In low and lower-middle-income countries, 82% of all damage and loss caused by drought concerned the agriculture sector. Between 2008 and 2018, across least developed countries and lower middle-income countries, 34% of disaster-related crop and livestock production losses were attributed to drought, followed by 19% to flooding events, 18% to severe storms and hurricanes, 9% to crop pests and animal diseases, 6% to extreme temperatures, and 1% to wildfires.