Excerpts from PROFITING FROM PAIN, a briefing paper published in May 2022 by Oxfam International.

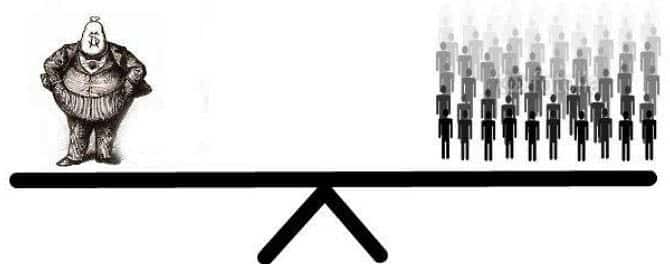

Billionaire wealth and corporate profits have soared to record levels during the COVID-19 pandemic, while over a quarter of a billion more people could crash to extreme levels of poverty in 2022 because of coronavirus, rising global inequality, and the shock of food price rises supercharged by the war in Ukraine. Oxfam’s research has found that:

- Billionaires have seen their fortunes increase as much in 24 months as they did in 23 years.

- Billionaires in the food and energy sectors have seen their fortunes increase by a billion dollars every two days. Food and energy prices have increased to their highest levels in decades. 62 new food billionaires have been created.

- The combined crises of COVID-19, rising inequality, and rising food prices could push as many as 263 million people into extreme poverty in 2022, reversing decades of progress. This is the equivalent of one million people every 33 hours.

- At the same time a new billionaire has been minted on average every 30 hours during the pandemic.

- This means that in the same time it took on average to create a new billionaire during the pandemic, one million people could be pushed into extreme poverty this year….

By every dimension, inequality has skyrocketed since the start of the pandemic.

Wealth inequality

According to Oxfam’s analysis of the latest data from Forbes:

- There are 2,668 billionaires in the world, 573 more than in 2020 when the pandemic began.

- These billionaires are collectively worth $12.7 trillion – a real-terms increase of $3.78 trillion (42%) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Total billionaire wealth is now the equivalent of 13.9% of global gross domestic product (GDP), up from 4.4% in 2000.

- The richest 10 men have greater wealth than the poorest 40% of humanity combined.

- The richest 20 billionaires are worth more than the entire GDP of sub-Saharan Africa.

- Elon Musk, the wealthiest man in the world, is so rich that he could lose 99% of his wealth and still be in the top 0.0001% of the world’s richest people. Since 2019 his wealth has increased by 699%.

Income inequality

COVID-19 is already set to drive the biggest systemic increase in income inequality ever seen. On top of this the rapidly rising prices of food and energy, which hit the incomes of the poorest hardest, are set to drive up global inequality still further.

- The incomes of 99% of humanity have fallen because of COVID-19, 28 with the equivalent of 125 million full-time jobs lost in 2021.

- It would take 112 years for the average person in the bottom 50% to make what someone in the top 1% gets in a year.

- The incomes of the richest have already recovered rapidly from the hit they took at the beginning of the pandemic while the incomes of the poorest have yet to recover, which is driving up income inequality.

- In 2021, the poorest 40% saw the steepest decline in income, which on average was 6.7% lower than pre-pandemic projections. This has led to rising income inequality, which had been declining since the 2000s as measured by the Gini index, but which in 2020 increased by 0.3% in emerging and developing economies.

Gender inequality

Governments have failed to prevent the pandemic from deepening longstanding gender inequalities in the economy. During the pandemic women were disproportionately pushed out of employment, especially as lockdowns and social distancing affected highly feminized workforces in the service sectors, such as tourism, hospitality, and care work. Increased unpaid work has barred millions of women from rejoining labor markets. And now, worldwide, women are expected to cope with the huge rises in food and energy prices in order to keep their families fed.

- The gender pay gap has widened: before the pandemic it was forecast to take 100 years to close; now it will take 136 years.

- In 2020, women were 1.4 times more likely to drop out of the labor force than men37 and took on three times more hours of unpaid care work.

- In 2021, there were 13 million fewer women in employment compared with 2019, while men’s employment recovered to 2019 levels.

- More than four million women workers have not been able to return to work in Latin America More than four million women workers have not been able to return to work in Latin America and the Caribbean, a trend driven by high levels of informal employment and increased care work.

Racial inequality

Across the world, the pandemic has hit racialized groups the hardest. This is directly linked to the historical legacies of white supremacy, including slavery and colonialism. Previous research by Oxfam has found examples of how Afro-descendant and Indigenous people in Brazil, Dalits in India, and Native American, Latinx, and Black people in the USA face disproportionate lasting impacts from the pandemic.

- During the second wave of the pandemic in England, people of Bangladeshi origin were five times more likely to die from COVID-19 compared with the White British population.

- 4 million more Black Americans would be alive today if their life expectancy was the same as White people’s. Before COVID-19, that alarming number was already 2.1 million.

- Half of all working women of color in the US earn less than $15 an hour, a widely used threshold for distinguishing low-wage workers in that country.

Health inequality

Good-quality healthcare is a human right, but it is too often treated as a luxury. Having more money in your pocket not only buys you access to healthcare, it also buys you a longer and healthier life.

- The life expectancy of people in high-income countries is 16 years longer than of those in low income countries.

- An estimated 5.6 million people die in poor countries every year due to lack of access to healthcare. That is more than 15,000 people every day.

- In São Paulo, Brazil, people in the richest areas can expect to live 14 years longer than those who live in the poorest areas.

- Ultimately, inequality, including a lack of access to healthcare, contributes to the death of at least one person every four seconds.

- The pandemic and the world’s failed response to it have exposed these vast health inequalities, fed off them, and made them far worse.

- As a result of the pandemic, four times more people have died in poorer nations than in rich ones.

- Some 11.66 billion vaccine doses have been administered globally50. If they had been distributed fairly then every adult in the world who wanted it could be fully vaccinated; instead, just 13% of people in low-income countries have been fully vaccinated.

- Every minute, four children around the world lose a parent or caregiver as a result of the pandemic. Almost half of them are in India, where over two million children have suffered such a loss.

- When COVID-19 struck, 52% of Africans lacked access to healthcare and 83% had no safety net to fall back on if they lost their job or became sick.

Inequality between countries

Before the pandemic, inequality between rich countries and lower-income countries was falling and had been for three decades. COVID-19 has reversed this trend. Low- and middle-income countries now face a lost decade while rich nations once again pull ahead.

Particularly concerning is the huge debt burden now facing so many countries, which undermines any hope of recovery and is preventing them from doing more to shield their citizens from soaring prices. It is becoming ever more costly for governments to service this debt, forcing them to make dramatic cuts to public services like health and education and leaving them unable to provide financial support to citizens.

- Fourteen out of sixteen West African nations intend to cut their national budgets over the next five years by a combined $26.8bn, in an effort to partly plug the gap of $48.7bn lost across the region in 2020 alone due to the pandemic.

- Debt servicing for all the world’s poorest countries is estimated at $43 billion in 2022 – equivalent to nearly half their food import bills and public spending on health care combined. In 2021, debt represented 171% of all spending on healthcare, education and social protection combined for low-income countries.

- 87% of COVID-19 loans made by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) come with conditions that demand that low- and middle-income country recipients adopt tough austerity measures that will further exacerbate poverty and inequality.

- 60% of low-income countries are now on the brink of debt distress.

“while over a quarter of a billion more people could crash to extreme levels of poverty in 2022 because of coronavirus”

Because of the corona virus? Oh really? So locking down the planet, immiserating the Global South, has nothing to with it according to Oxfam, it’s all down to the virus! What nonsense! This global disaster was caused by capitalism, not a virus! Lockdowns etc, have done absolutely nothing to stop the spread of the virus. Instead they’ve driven millions into abject poverty.

William — The sentence actually says: “over a quarter of a billion more people could crash to extreme levels of poverty in 2022 because of coronavirus, rising global inequality, and the shock of food price rises supercharged by the war in Ukraine.”

You may not like the lockdowns, but that does not justify misquoting.

“Lockdowns etc, have done absolutely nothing to stop the spread of the virus” apart from their intelligent and community-led use in China, where all the evidence shows that lockdowns, vaccines and other hugely-popular public health measures saved a massive number of lives.

“China’s largest city, Shanghai, largely reopened Wednesday morning after a two-month lockdown that successfully beat back an outbreak of the virulent Omicron BA.2 subvariant of COVID-19. The event was a triumph of public health mobilization, as the outbreak, which reached a peak of almost 30,000 infections per day in mid-April, took the lives of fewer than 600 people, mostly elderly and unvaccinated. For the most part, residents remained in their homes, with the internet their principal connection to the outside world. Food deliveries and supplies of other necessities were organized through the country’s extensive networks of housing blocks and neighborhood committees, later supplanted by the government.”

(WSWS, 1 June 2022)