(Andreas Kambanis via Flickr under CC by SA 2.0)

by Julie Brigham-Grette and Andrea Dutton

The Conversation, May 17, 2021

While U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken draws attention to climate change in the Arctic at meetings with other national officials this week in Iceland, an even greater threat looms on the other side of the planet. New research shows it is Antarctica that may force a reckoning between the choices countries make today about greenhouse gas emissions and the future survival of their coastlines and coastal cities, from New York to Shanghai.

That reckoning may come much sooner than people realize.

The Arctic is losing ice as global temperatures rise, and that is directly affecting lives and triggering feedback loops that fuel more warming. But the big wild card for sea level rise is Antarctica. It holds enough land ice to raise global sea levels by more than 200 feet (60 meters) – roughly 10 times the amount in the Greenland ice sheet – and we’re already seeing signs of trouble.

Scientists have long known that the Antarctic ice sheet has physical tipping points, beyond which ice loss can accelerate out of control. The new study, published in the journal Nature, finds that the Antarctica ice sheet could reach a critical tipping point in a few decades, when today’s elementary school kids are raising their families.

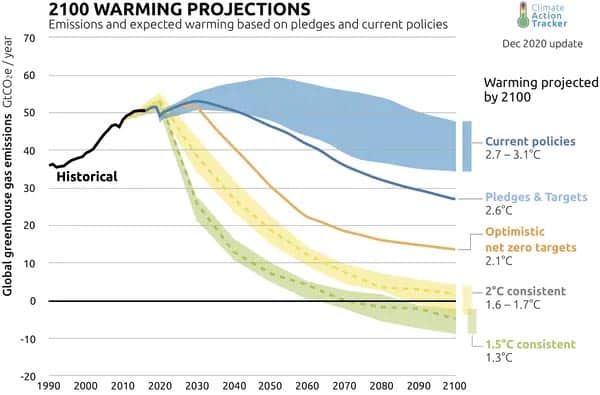

The results mean a common argument for not reducing greenhouse gas emissions now – that future technological advancement can save us later – is likely to fail. The new study shows that if emissions continue at their current pace, by about 2060 the Antarctic ice sheet will have crossed a critical threshold and committed the world to sea level rise that is not reversible on human timescales. Pulling carbon dioxide out of the air at that point won’t stop the ice loss, it shows, and by 2100, sea level could be rising more than 10 times faster than today.

The tipping point

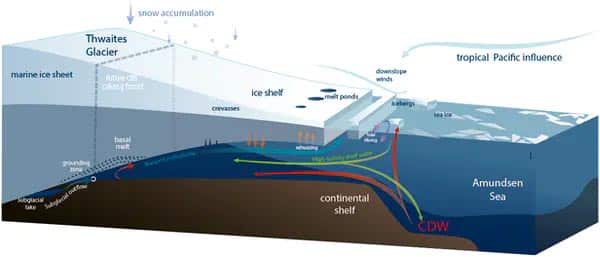

Antarctica has several protective ice shelves that fan out into the ocean ahead of the continent’s constantly flowing glaciers, slowing the land-based glaciers’ flow to the sea. But those shelves can thin and break up as warmer water moves in under them. As ice shelves break up, that can expose towering ice cliffs that may not be able to stand on their own.

There are two potential instabilities at this point. Parts of the Antarctic ice sheet are grounded below sea level on bedrock that slopes inward toward the center of the continent, so warming ocean water can eat around their lower edges, destabilizing them and causing them to retreat downslope rapidly. Above the water, surface melting and rain can open fractures in the ice. When the ice cliffs get too tall to support themselves, they can collapse catastrophically, accelerating the rate of ice flow to the ocean.

Warmer circumpolar deep water can get under ice shelves and eat away at the base of glaciers. (Scambos et. al. 2017. Global Planetary Change)

The study used computer modeling based on the physics of ice sheets and found that above 2 C (3.6 F) of warming, Antarctica will see a sharp jump in ice loss, triggered by the rapid loss of ice through the massive Thwaites Glacier. This glacier drains an area the size of Florida or Britain and is the focus of intense study by U.S. and U.K. scientists.

To put this in context, the planet is on track to exceed 2 C warming under countries’ current policies. Other projections don’t account for ice cliff instability and generally arrive at lower estimates for the rate of sea level rise. While much of the press coverage that followed the new paper’s release focused on differences between these two approaches, both reach the same fundamental conclusions: The magnitude of sea level rise can be drastically reduced by meeting the Paris Agreement targets, and physical instabilities in the Antarctic ice sheet can lead to rapid acceleration in sea level rise.

The disaster doesn’t stop in 2100

The new study, led by Robert DeConto, David Pollard and Richard Alley, is one of the few that looks beyond this century. One of us is a co-author.

It shows that if today’s high emissions continued unabated through 2100, sea level rise would explode, exceeding 2.3 inches (6 cm) per year by 2150. By 2300, sea level would be 10 times higher than it is expected to be if countries meet the Paris Agreement goals. A warmer and softer ice sheet and a warming ocean holding its heat for centuries all prevent refreezing of Antarctica’s protective ice shelves, leading to a very different world.

The vast majority of the pathways for meeting the Paris Agreement expect emissions will overshoot its goals of keeping warming under 1.5 C (2.7 F) or 2 C (3.6 F), and then count on future advances in technology to remove enough carbon dioxide from the air later to lower the temperature again. The rest require a 50% cut in emissions globally by 2030. Although a majority of countries – including the U.S., U.K. and European Union – have set that as a goal, current policies globally would result in just a 1% reduction by 2030.

(Climate Analytics and NewClimate Institute)

It’s all about reducing emissions quickly

Some other researchers suggest that ice cliffs in Antarctica might not collapse as quickly as those in Greenland. But given their size and current rates of warming – far faster than in the historic record – what if they instead collapse more quickly?

As countries prepare to increase their Paris Agreement pledges in the runup to a United Nations meeting in November, Antarctica has three important messages that we would like to highlight as polar and ocean scientists.

First, every fraction of a degree matters.

Second, allowing global warming to overshoot 2 C is not a realistic option for coastal communities or the global economy. The comforting prospect of technological fixes allowing a later return to normal is an illusion that will leave coastlines under many feet of water, with devastating economic impacts.

Third, policies today must take the long view, because they can have irreversible impacts for Antarctica’s ice and the world. Over the past decades, much of the focus on rapid climate change has been on the Arctic and its rich tapestry of Indigenous cultures and ecosystems that are under threat.

As scientists learn more about Antarctica, it is becoming clear that it is this continent – with no permanent human presence at all – that will determine the state of the planet where today’s children and their children will live.

Julie Brigham-Grette is Professor of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Andrea Dutton is Professor of Geoscience, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Republished from The Conversation, under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.