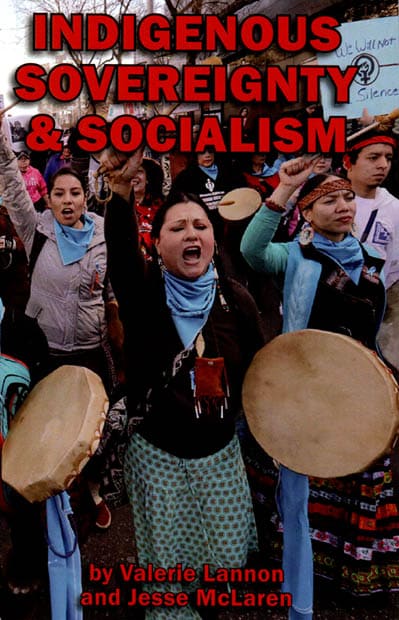

Valerie Lannon and Jesse McLaren

INDIGENOUS SOVEREIGNTY & SOCIALISM

Toronto: International Socialists, 2018

reviewed by Richard Fidler

This small book (123 pages) is an ambitious effort, with three objectives: “to outline the history of European colonization and the Canadian state… to outline the long and ongoing history of Indigenous resistance to colonialism… [and] to explore the dialogue between Indigenous sovereignty and socialism over the past 150 years.”

Describing themselves as “settlers and socialists involved in the climate justice movement,” the authors say they want to “contribute to this ongoing conversation — learning from Indigenous resistance and contributing to settler solidarity.”

On the whole, they do this well. The result is a valuable contribution, one of the few written from a Marxist perspective, to the growing literature on the mass Indigenous movement that is now in the vanguard of the fight in Canada against climate catastrophe.

The book addresses, in chronological sequence, seven aspects of Canada’s Indigenous history. This review will highlight some salient features. The full text incorporates a wealth of documentation, much of it based on Indigenous peoples’ narratives and research.

I. First Peoples

This chapter describes the communal societies of the Indigenous peoples encountered by the first European settlers, drawing on studies by Marx, Engels and North American Marxist and Indigenous scholars. “European socialists saw the democracy and equality of Turtle Island [North America] as something to be celebrated and spread, but European rulers saw it as a barrier to capital accumulation that had to be crushed.”

II. Capitalism and Colonialism

Europeans saw the land as theirs for the taking, invoking a “doctrine of discovery” that treated it as terra nullius, a land without people. Where necessary, they cajoled the Indigenous into signing unequal treaties, interpreting them as a surrender of Native sovereignty, while their own undertakings were subsequently ignored. Colonialism, with or without treaties, entailed the dispossession of the Indigenous populations, and in some cases their proletarianization. The authors quote Howard Adams, a Saskatchewan Métis who pioneered in the Marxist analysis of Canada’s oppression of the Indigenous peoples:

“The structure of racism and the form of racial violence in Canada was dictated by two facts: the conquest of Indian territory and the exploitation of Aboriginal labor in the pursuit of wealth from fur pelts…. Indian communal society was transformed into an economic class of laborers by European fur trading companies, particularly the Hudson’s Bay Company.”

They add:

“The competition for market dominance — between competing companies like the HBC and the Northwest Company, and competing colonial states like England and France — transformed hunting, trapping and fishing from activities that maintained societies in equilibrium with nature to unsustainable profit-driven markets. Indigenous societies had maintained their metabolism with nature for thousands of years, but the introduction of the capitalist market led to a metabolic rift: over-hunting of beaver in the forests, fish in the streams, buffalo on the plains and whales in the Arctic. This undermined food security, furthering colonial control.”

III. Canada: A Prison-House of Nations

The British Act creating the Dominion of Canada bolstered colonial domination over Indigenous peoples and the national oppression of Québécois and Acadians. The subsequent consolidation and expansion westward of the new Canadian state entailed the violent suppression of Indigenous and Métis resistance and the theft of their lands, whether by treaty or not (as in British Columbia).

The Indian Act replaced traditional tribal governance with band councils dominated by a federal government bureaucracy. The subdivision of Indigenous lands into reserves was designed, as an Indian Affairs commissioner wrote, to destroy “the tribal or communist system.” Indigenous culture was targeted through residential schools, forcibly removing within a century 150,000 children from their communities, traditions and teachings in order to “kill the Indian in the child.”

Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, the authors note, led the genocidal project of building a colonial and capitalist state by trying to destroy Indigenous nations. He is hailed in Canadian mythology as a “nation builder,” but “the Canadian state he helped build was a prison-house of nations; it was built on colonizing First Nations and Inuit people, deporting Acadians, conquering Quebec, oppressing the Métis, and exploiting Indigenous and immigrant workers.”

While Indigenous labour was employed extensively in Canada’s resource-based economy in the early 20th century, Indigenous workers were considered unreliable assets by employers because of their surviving links with their lands, communities, and customs, which served to offset the super-exploitation of their labor. “Canadian capitalism used racism to justify colonizing Indigenous territory, to extract more surplus value from Indigenous workers, and also to weaken solidarity.” However, the authors cite numerous examples of Indigenous resistance to these attacks.

IV. White Paper, Red Power

The biggest attack on Indigenous peoples in the post-WWII period came with the appropriately named “White Paper” on Indian policy, produced in 1969 by the minister of “Indian Affairs,” Jean Chrétien. It aimed to abolish Indigenous status, do away with the treaties, and leave Canada’s quarter-million treaty Indians then covered by federal services at the mercy of the provinces. The White Paper “would have been the death knell of distinct First Nations cultures and rights, as paltry as these rights were under the Indian Act, including funding for housing, health and education.” It “is inconceivable,” Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau proclaimed, “that one section of a society should have a treaty with another section of society…. They should become Canadians as all other Canadians.”

The White Paper sparked a new rise of Indigenous resistance — the Red Power movement — expressed in such organizations as the Native Alliance for Red Power (modeled on the Black Panthers),[1] Equal Rights for Native Women, to fight the sexist provisions in the Indian Act, and the Saskatchewan Native Action Committee (SNAC), founded by Howard Adams to “provide a radical alternative to a leadership he saw as co-opted.”

Although Trudeau was forced to withdraw the White Paper, its thinking has informed government policy and practice to this day. In the 1970s, Ottawa launched a “comprehensive claims process” ostensibly to settle unresolved land title issues among Indigenous nations that had not signed treaties. But as in the “model” James Bay and Northern Quebec “modern” treaty in the mid-1970s between the Cree Nation and the Quebec and federal governments, which allowed Quebec to develop hydro-electric generation throughout much of the province’s territory, governments always condition any such agreement (and there are very few) on a prior surrender of indigenous title.

When Pierre Trudeau “patriated” the Canadian constitution from Britain, a massive Indigenous mobilization managed to gain the last-minute adoption of a section (35) of the new Constitution recognizing “[t]he existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada.” However, it was left to the courts to clarify what those rights were in substance. The result, as indigenous scholar Pam Palmater argues, has been an “extensive, costly litigation of our rights on a right by right, species by species and First Nation by First Nation basis.” And any recognition of such rights is always made subordinate to (“reconciled with”) Canadian sovereignty and Canadian law.

V. Recognition and Reconciliation

A Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was appointed in 1991 following the standoff between the Canadian army and the Mohawks of Kanehsatake defending against a private golf course on their lands. In 1996 the commission issued a five-volume 4,000 page report with 440 recommendations “covering all the key aspects of the lives of Aboriginal peoples, albeit within the confines of the Canadian state and economic system.” Among these were:

- Establishment of a new Nation-to-Nation relationship

- Creation of an aboriginal parliament

- Termination of the Indian Act and the department enforcing it

- A public inquiry into residential school abuse

- Fulfillment of existing treaties and a new framework for negotiating new treaties

- Recognition of the Aboriginal right to self-determination

- Provision of land sufficient to foster Aboriginal economic self-reliance and cultural and political autonomy

- Financing of Aboriginal economic development

- A series of measures to establish Aboriginal control over social services, education.

Critically, it called for doing away with racist legal covers for colonization: “concepts such as terra nullius and the doctrine of discovery are factually, legally and morally wrong.”

Most of these recommendations (many of them echoed 20 years later by the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission) have been ignored by governments, which instead employ a “recognition and reconciliation” approach that (in the words of Indigenous scholar Glen Coulthard) entices Indigenous peoples “to identify, either implicitly or explicitly, with the profoundly asymmetrical and nonreciprocal forms of recognition either imposed on or granted to them by the settler state and society.”

Most recently, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, initially opposed by the Harper government, has given the First Nations a new weapon in their struggle. Indigenous leaders point out that the UNDRIP urges states to give legal recognition and protection to the lands, territories and resources of the Indigenous peoples, and to condition the adoption of measures that may affect them on “their free, prior and informed consent.”[2]

VI. Indigenous Resistance Today

This section documents numerous struggles led by a militant new leadership — examples are the activists in Idle No More and Defenders of the Land — prepared to engage in direct action initiatives, to stand up to corporate and government intrusions on Indigenous lands, and to work with non-Indigenous activists in defense of First Nations rights and the environment.

“Indigenous resistance and solidarity has helped transform the small environmental movement of the 1990s into the broad climate justice movement of today. While loggers angrily denounced environmentalists protesting at Clayoquot sound in 1993, in 2013 Unifor (representing some tar sands workers) signed the Solidarity Accord with the Save the Fraser Declaration, stating: ‘We, the undersigned, say to our First Nations brothers and sisters, and to the world, that we are prepared to stand with you to protect the land, the water and our communities from the Enbridge pipelines and tankers project and similar projects to transport tar sands oil.” … With this spirit the climate justice movement — unifying labour, environmental and Indigenous movements — flows from the heart of the tar sands across Turtle Island.”

A major battle today is the fight to stop a planned expansion of the TransMountain pipeline, now owned by the federal government, that would triple its flow of tar-sands bitumen from Alberta to the Pacific Coast. Another battle is in northern British Columbia, on Wet’suwet’en lands, where the B.C. government is building a gas pipeline to serve a huge LNG complex on the coast that is the biggest private-sector undertaking in Canada. In both these battles, the companies and governments involved have gone to great lengths, with some success, to enlist support from Indian Act band councils hoping to alleviate their peoples’ poverty through construction jobs and other promised benefits.

“Whereas colonial violence in the 19th century paved the way for the railroad,” the authors comment, “colonial violence today facilitates the latest ‘nation-building project’: tar sands and pipelines.”

VII. Indigenous Sovereignty & Socialism

The authors list key immediate demands raised in the struggles outlined in previous pages. “These reforms, and the fight necessary to win them, are essential to push back against the injustice of the Canadian state.” And they single out the First Nations’ role in fighting climate change, although surprisingly they do not mention the Leap Manifesto’s recognition that

“This leap must begin by respecting the inherent rights and title of the original caretakers of this land. Indigenous communities have been at the forefront of protecting rivers, coasts, forests and lands from out-of-control industrial activity.”[3]

They note, however, the obstacles and limits to achieving these goals posed by the institutions of the Canadian state: courts, governments, legislatures, etc. They call for “revolutionizing settler society, by building unity and solidarity within the working class, which includes Indigenous workers.”

“Only the overthrow of capitalism and its replacement with socialism — a truly democratic, environmentally sustainable, economically and socially just society — can stop capitalism’s endless drive to accumulate, achieve Indigenous sovereignty, and heal the metabolic rift that separates us and which alienates us, mind and body, from nature.”

Socialism, they say, “can only be won by the leadership of Indigenous peoples themselves, in alliance with settlers [their compendious name for all non-Indigenous]…. This means breaking free of Canada’s prison-house of nations and removing the three mountains of sexism, racism and national oppression…, intertwining Indigenous national liberation with working class revolution.”

What would this entail in practical terms, as a strategic objective for socialists? A constituent assembly, a plurinational state in place of the colonialist capitalist state? The authors don’t say. Here we encounter a certain tension that runs throughout this book.

Is Indigenous oppression to be analyzed as essentially national oppression, or is it mainly a distinct form of class oppression, albeit deepened by national oppression? The book is unclear on this. For example, the authors say the Canadian state aimed at both genocide of the Indigenous population and their proletarianization as cheap labor. But this confuses the objective with its effect. Against all odds, the Indigenous peoples survived, and today seek to develop their remaining lands in their interests as First Nations. Their urbanization and proletarianization — as the authors note, “most Indigenous people are part of the paid workforce” — is the result of the theft of much of their land by the colonizing regime, and the poverty of most of the reserves.

Most urban Indigenous people retain some links and identification with their land-based communities, however. And although it may be difficult for many socialists to grasp this, most Indigenous militants see their future in the defense of their lands, and in the belief that their self-determination as peoples or First Nations lies in achieving unfettered ownership and control over the collective development of their lands, thereby avoiding or escaping the proletarian status of their landless settler co-workers. These aspirations are progressive, and suggest ways to overcome the colonialist structure of the Canadian state.

The Indigenous nations are many, and widely dispersed throughout the territorial expanse of Canada today. But their struggles for self-determination have the potential to win important allies from other national struggles within the state. As Glen Coulthard notes,

“the significant political leverage required to simultaneously block the economic exploitation of our people and homelands while constructing alternatives to capitalism will not be generated through our direct actions and resurgent economies alone. Settler colonization has rendered our populations too small to affect this magnitude of change. This reality demands that we continue to remain open to, if not actively seek out and establish, relations of solidarity and networks of trade and mutual aid with national and transnational communities and organizations that are also struggling against the imposed effects of globalized capital, including other Indigenous nations and national confederacies; urban Indigenous people and organizations; the labor, women’s GBLTQ2S (gay, bisexual, lesbian, trans, queer, and two-spirit), and environmental movements; and, of course, those racial and ethnic communities that find themselves subject to their own distinct forms of economic, social, and cultural marginalization.”[4]

Obvious candidates for solidarity include the Québécois, whose national self-determination is constrained by the Canadian state structures and institutions. It is no accident that the progressive wing of Quebec’s pro-sovereignty movement, Québec solidaire, fully recognizes the right to self-determination of the Indigenous peoples, and welcomes the opportunity to establish equal and harmonious relations between an independent Quebec and sovereign First Nations cohabiting within it.

QS promises to establish a democratically elected Constituent Assembly that will adopt the constitution of an independent Quebec. The Assembly, it says, “will also reaffirm the sovereignty of the Aboriginal nations” and these nations will be invited to “join in this democratic exercise through whatever ways they decide, including, if they wish, by accepting an important place within the framework of the Constituent Assembly itself.” I append my translation of the part of the QS program that is addressed to relations with the Aboriginal Peoples.

The book under review acknowledges that Québec solidaire “sees Quebec sovereignty not as an end in itself but as a means to win democratic demands including Indigenous sovereignty.” But it is vague about whether or how this might play some role in what it terms “the ultimate strategy to win Indigenous sovereignty and socialism,” which it says is “to break free of the prison-house of nations which is the Canadian state, reclaiming land and labour.” Yet there is no question that a Quebec decision to break from the existing Canadian state, by hugely disrupting the territorial and political unity of Canada, would do more than any First Nations actions, by themselves, to put the recomposition of Canada, with or without Quebec, in a radically different — and plurinational? — form on the agenda.

The book does not address many aspects of today’s Indigenous reality in Canada. Among these are the conflicts between and within many First Nations over economic development, as illustrated by the success oil and gas interests have achieved, with government support, in aligning band councils behind pipeline expansion projects. Another is the difficulty in forging credible militant leaderships at the pan-Canadian level, where there is a long record of opportunistic collaboration with governments and corporate interests on the part of the Assembly of First Nations chiefs.[5]

The book would have benefited as well from drawing attention to outstanding examples in the literature of Indigenous community attempts to manage their natural resources in harmony with Mother Earth. Important accounts include Glen Coulthard’s chapter on his Dene Nation’s struggle for self-determination in northern Canada, registered in the Denendeh proposal and its articulation in the Dene Declaration of 1975. Another is Shiri Pasternak’s stirring account of the Barriere Lake Algonquins experience in achieving a trilateral agreement with the Quebec and Canadian governments giving them jurisdiction over their land, and in particular sustainable management of its rich timber resources — an accord subsequently sabotaged by government officials.[6]

A great strength of the book, however, is its citation and quotation of accounts by Indigenous activists and scholars in order to develop its argument. Although it includes a bibliography of their sources, I found myself wishing in many places that the authors had provided footnoted page references to passages cited in the text. And a serious omission — especially in a text that covers so many struggles and other resistance experiences — is the lack of an index that would help the reader find or relocate particular references in the text.

It seems the book is only available at present within Canada, at CDN $15 ($10 + $5 shipping) payable to Socialist Worker, P.O. Box 339, Station E, Toronto M6H 4E3. The authors should consider producing a pdf or e-book version.

Notes

[1] The NARP program is reproduced in a pamphlet I authored in 1970, Red Power in Canada, available on-line in the Socialist History Project.

[2] No Canadian court has yet interpreted these clauses in a definitive way. While Indigenous lawyers argue that such consent is mandatory, I am leery of some ambiguous wording in the Declaration. For example, the key Articles 19 and 32 both provide that “States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent….” That is not the same thing as saying that states “shall obtain” this FPIC. Thus courts may well choose to override Indigenous objections to a program or project on the grounds that the government authority manifested sufficient good faith in its (unsuccessful) effort to obtain consent, especially when conflicting Indigenous and private or government property claims are at issue, the latter being held to prevail in the general public interest.

[3] A Call for a Canada Based on Caring for the Earth and One Another, https://leapmanifesto.org/en/the-leap-manifesto/.

[4] Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Foreword by Taiaiake Alfred). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014, p. 173.

[5] Excellent sources on these issues (and many others) are Arthur Manuel’s books: The Reconciliation Manifesto: Recovering the Land, Rebuilding the Economy (Toronto: Lorimer, 2017); and its predecessor Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-Up Call (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2015).

[6] Shiri Pasternak, Grounded Authority: The Algonquins of Barriere Lake Against the State. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

APPENDIX

Québec Solidaire on the Sovereignty of the Aboriginal Peoples

- Québec solidaire recognizes that the aboriginal peoples have never renounced their sovereignty, either by treaty or otherwise. They remain sovereign peoples, therefore. Some of them occupy vast territories on which there are very few non-aboriginal residents.

- Québec solidaire recognizes that for all aboriginal peoples their sovereignty means they are free to determine their future and that this is an inherent right. This reality must be recognized if we are to avoid having a policy of “two weights, two measures.” The Quebec nation cannot deny to other peoples what it claims for itself. If its very existence as a people gives it the full right to self-determination, this should apply as well to the aboriginal peoples. It is a fundamental right, not a question of numbers.

- Québec solidaire recognizes that to achieve equal relations with the aboriginal peoples, Quebec’s territorial integrity as a precondition must be replaced by a completely different notion, that of the necessary cohabitation on the same territory of sovereign peoples, each free to determine its own future.

This position should allow more harmonious relations since they will be based on mutual respect and trust. This recognition will of course have to have very concrete territorial and other repercussions, and help to remedy the injustices still suffered by the aboriginal peoples by ensuring their full social, cultural, economic and political development. The negotiations to this effect should be conducted in respect of each and every one, including the non-aboriginal populations living in the territories in question. In this sense, the struggle against the racism suffered by aboriginal peoples remains one of the key concerns in a genuine recognition of their rights.

- Any future negotiation should be informed by Québec solidaire’s ecological vision. The discussions will have a quite different character when territorial occupation is considered a responsibility we must share, aboriginal and non-aboriginal alike, and not as a way to exploit and market resources until they are exhausted, as allowed by many states and practiced by many companies.

From Programme politique de Québec solidaire, pp. 85-86.