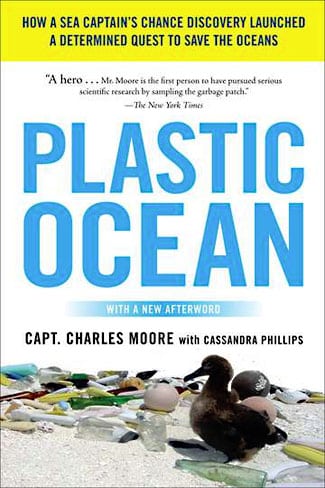

Charles Moore,

Charles Moore,

with Cassandra Phillips

Plastic Ocean:

How a Sea Captain’s Chance Discovery Launched a Determined Quest to Save the Oceans

Penguin Group, 2011

reviewed by Ian Angus

(This review was first published in the March 2014 issue of Monthly Review, and is posted here with permission. There are some minor differences between this text and the one on the MR website.)

Four decades ago, when most greens were blaming pollution on population growth and personal consumption, socialist environmentalist Barry Commoner showed that neither could account for the radical increase in pollutants since the end of World War II. In The Closing Circle (New York, Alfred E. Knopf, 1971), he argued that “the chief reason for the environmental crisis … is the sweeping transformation of productive technology since World War II.” (177) In particular, he pointed to dramatic increases in the production and use of materials not found in nature, synthetics that cannot degrade and so become permanent blights on the earth.

Commoner described natural processes as essentially circular. “In the ecosphere every effect is also a cause: an animal’s waste becomes food for soil bacteria; what bacteria excrete nourishes plants; animals eat the plants.” (Closing Circle, 39)

But modern industrial systems are characterized by linear processes: “machine A always yields product B, and product B, once used, is cast away, having no further meaning for the machine, the product, or the user.”

“We have broken out of the circle of life, converting its endless cycles into man-made, linear events…. [M]an-made breaks in the ecosphere’s cycles spew out toxic chemicals, sewage, heaps of rubbish – testimony to our power to tear the ecological fabric that has, for millions of years, sustained the planet’s life.” (Closing Circle, 11-12)

The petrochemical industry in particular has generated a huge range of materials that nature cannot recycle and reuse. In the first decade after World War II, plastics were promoted for and used primarily to make durable products: furniture, tires, automobile and airplane components and the like. But while plastics are still widely used for long-lasting products, the industry has found its biggest success with throwaways, products specifically designed to be used once and discarded.

Commoner described the trend to disposables in 1971, but he couldn’t have known then how bad it would get when the plastic industry really got going.

When The Closing Circle was published, there were no plastic soft-drink bottles, and no one imagined that giant corporations would one day brand and bottle tap water. Today, 72 billion plastic bottles are produced every year.

Similarly, Commoner wrote before the introduction of plastic grocery bags, which weren’t adopted by major supermarket chains until the early 1980s. Today over 500 billion bags are made every year.

Bottles and bags, together with blister packs, polystyrene tubs, foam peanuts, bubble wrap, styrofoam trays, candy wrappers, and a multitude of other forms of packaging, now account for a third of the plastic produced each year worldwide.

It’s bizarre process: products designed to be thrown away are made from materials that never die.

The second of Barry Commoner’s famous Four Laws of Ecology is Everything must go somewhere. As he wrote, that’s a critically important issue for materials that degrade extremely slowly, if at all. Some plastic has been burned, some has been recycled, but most – billions and billions of tons of it – remains on earth, and will do so indefinitely.

In his remarkable new book Plastic Ocean, Charles Moore reports on the part of the “unstoppable avalanche of nonessentials” (39) that ends up in the oceans, where it chokes and poisons fish, mammals and birds, and endangers human life. By turns a memoir, an environmental exposé, and a call to action, it is a dramatic account of what Moore has learned in fifteen years of collecting plastic debris in the Pacific Ocean, studying its effects on marine wildlife, tracing its origins, and campaigning to stop it.

Moore is a rare creature, a activist researcher with the means and determination to work independently of academic and corporate restrictions. Using a family inheritance – ironically, his grandfather was president of Hancock Oil – he founded the Algalita Marine Research Foundation in 1994, hoping “to shorten the distance between research and restoration of the marine environment.

“The ‘spill, study, and stall’ crowd – advocating the hundred-year-old petroleum industry’s strategy – demands a science of valueless facts to provide a ‘complete’ mechanistic understanding of a problem before embarking on any solution. Endless, purposeful delay pending perfect ‘sound science’ enforces a form of intellectual sadomasochism driven by the need to preserve profits, not benefit society.” (329)

In 1997, while sailing his research boat between Hawaii to California, Moore was initially bemused and then shocked by the amount of plastic litter that floated by, a thousand miles from the nearest land.

He later learned that the material he saw was concentrated in the North Pacific Gyre, an area where intersecting currents, prevailing winds, and the earth’s rotation combine to produce a slow moving whirlpool more than twice the size of Texas. There are huge gyres in each of the world’s oceans. Any plastic light enough to float that enters the sea – either directly by spills and dumping, or carried from land by wind or rivers – is likely to be swept into a gyre, where it will circulate indefinitely, broken by waves and wind into ever-smaller particles.

“Anthropogenic debris – man-made trash, 80-90 percent of it plastic – has broken the reverie of pristine perfection that is the ocean’s essence. It’s become her most common surface feature …. Trash has superseded the natural ocean sights, stamping a permanent plastic footprint on the ocean’s surface.” (70)

Bear in mind that although people have been dumping garbage in oceans for millennia, we’ve only been throwing plastic away for fifty years. The accumulation of millions of tons of plastic in ocean gyres is powerful confirmation that the nature of garbage changed qualitatively in the last half of the twentieth century.

On the Internet, it’s easy to find articles that describe the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” as a floating island of plastic debris, 60 to 90 feet thick. Moore dissociates himself from such fantasies. He describes it as a thin plastic soup – untold millions of plastic particles, interspersed with disposable lighters, pieces of fish net, broken buoys and other objects that haven’t broken up yet. If anything, that makes it much more dangerous to the birds, mammals and fish to whom small colored particles suspended in water look like food.

Because this isn’t just about esthetics, the ocean equivalent of roadside trash. Plastic isn’t just unsightly – it has made the ocean deadly for its inhabitants. Cases of large animals killed by plastic have been widely publicized – thousands of birds, turtles, seals, and even whales die every year, their throats and guts clogged with indigestible debris – but plastic affects the entire animal food chain. As Moore’s research has proven, even tiny lanternfish ingest plastic particles – and since they are the main food of tuna, cod, salmon and shark, many of those particles become part of human diets.

In addition to causing direct physical damage to digestive systems, plastic particles are now known to be an efficient delivery system for toxic chemicals, some from their manufacturing processes, others absorbed as they float by polluted shorelines. Many of these are endocrine disrupters, chemicals that interfere with biological processes, including foetal development. In addition to causing premature death for countless animals, those chemicals ultimately concentrate in the fish that humans eat, contributing to a host of diseases.

This is all well-known to science, but there has been little action to stop plastic pollution. The industry has successfully diverted attention away from the production of throwaway plastics to individual consumer behavior – the “solutions” they promote involve cleaning up or recycling products that never should have been made in the first place.

Moore discovered this personally in 2000, when a conference on marine debris rejected his request for discussion of the plastics industry. For the organizers, he realized, “plastics pose a ‘handling’ problem – that is, a ‘people problem,’ not a material problem. It’s all our fault, in other words.” (162)

At a similar conference in 2011, government and industry representatives worked with the organizers to draft what was to be “a plan to lead the way to a debris-free ocean” – but the draft didn’t even mention plastic until Moore and other activist-scientists loudly objected.

As Moore told a reporter at the time, trying to clean up the oceans while doing nothing to stop production of disposable plastic is like “trying to bail out a bathtub with the tap still running.” (165)

Ultimately, Moore concludes, the problem is a system that puts corporate interests ahead of the environment, even ahead of human survival.

“Because change is hard and powerful people and organizations benefit from the status quo. Plastics are a high-stakes game, and those who run it can ill afford to lose control of the playing field. But ridding the oceans of plastic means stopping all plastic inputs ― now.” (292)

That will only happen if governments “confront industry and put responsibility where it belongs – on plastics producers – not volunteer cleanup crews, taxpayer-supported government agencies, and NGOs.” (164)

Unfortunately, despite his indictment of the plastics industry, his rejection of solutions that blame consumers, and his critique of green organizations that ignore “the core issue: the ever-growing volume of plastic products and packaging across the world,” (300) Moore stops short of suggesting a strategy for stopping the plastic plague. No one could expect him to provide a detailed roadmap, but his concluding chapter doesn’t offer much more than a vague hope that people will demand change.

He argues that “the science and technology that will liberate us from pollution and meaningless labor are available” (332) and predicts that a future generation will “unplug itself from the economy of constant input and output of junk,” (334) but he doesn’t address the critical question: how do we get there from here? Which battles can be won in the short term and which ones will require radical social change? What kinds of economic and social changes are needed?

Above all, how can we build movements that are strong enough to overcome the power of the giant corporations whose profits depend on pollution?

The book’s failure to address such questions isn’t really surprising: many books on environmental problems are published, but few go beyond exposé to explain why, in Commoner’s words, “the present system of production is self-destructive; the present course of human civilization is suicidal.” (Closing Circle, 295) Even fewer take the giant step of proposing practical steps towards the ecological revolution that is clearly needed.

It’s only a disappointment that Plastic Ocean doesn’t take that step because most of the book seems to be leading towards a call for system change. Perhaps this is one more proof that in these times it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

Whatever the reason, and despite that weakness, Plastic Ocean deserves a wide audience. It is a fine example of what used to be called “peoples’ science” – it’s as dramatic as many novels, it’s accessible to readers with no background in science, and it’s an important contribution to broad awareness of the ever-growing conflict between our systems of production and the circle of life.