A good starting point would be to learn to ‘fail better.’ There are no predetermined solutions and we have to be open to the possibility of being wrong.

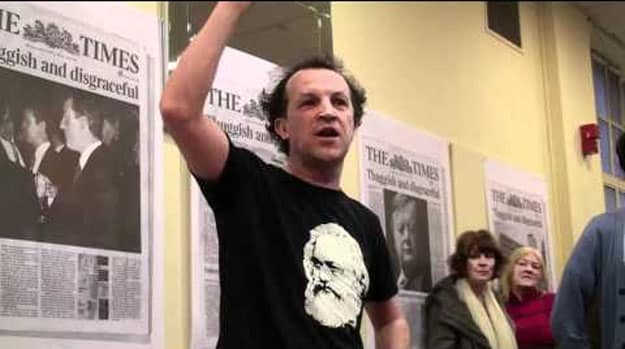

Derek Wall, a founder of the Green Left and the Ecosocialist International Network,

is International Coordinator of the UK Green Party.

His books include The No Nonsense Guide to Green Politics and The Rise of the Green Left.

TURNING DEFEAT INTO VICTORY

by Derek Wall

reposted with permission from Morning Star, January 27, 2013

In Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot two tramps wait in a bleak landscape for a saviour who never arrives.

While Beckett was known neither for his sunny disposition nor his political commitment, some of his thinking is instructive for those who want to change society for the better.

He advised that in the face of adversity we should remain strong, insisting: “Fail, try again, fail, try again, fail, try again, fail better.”

For decades the left has been on the back foot.

The three main political parties work for the needs of the 0.001 per cent – their god is the market and our collective needs are ignored.

The government is destroying our health system, assaulting education, attacking those with disabilities and attempting to make ordinary people poorer. The need to fight back is more urgent than ever.

Certainly there has been some valiant resistance – the student protests were followed by the Occupy movement and 20,000 marched against the closure of Lewisham Hospital at the weekend, to name just a few examples.

However Occupy was cleared away, the Con-Dems are as committed as ever to turning the NHS into a cash cow for US-based multinationals, and the neoliberal agenda remains dominant.

But we mustn’t be daunted. We need to turn defeat into victory, and learning to “fail better” would be a start.

It doesn’t work to point out the failure of others on the left as a defence of one’s own strategy.

The cyclical crises of the Socialist Workers Party provide a soap opera for others on the left which have been used by some to argue that “top-down” Leninist structures are destined to founder.

While I am not a Leninist, it hardly seems fair to blame Lenin for the failures of British left parties a century after he wrote.

Some on the left have called for an alternative which learns from Occupy and other decentralised networks, and there’s much to sympathise with in these arguments – if activists don’t feel that they have democratic input into an organisation, the organisation will be brittle and internal conflict will be both more likely and deeper.

But at the same time it seems that every generation of young revolutionaries criticise democratic centralism and call for new participatory organisations.

In the 1950s EP Thompson and Raymond Williams left the Communist Party and launched the New Left. In the 1960s Danny Cohn-Bendit and the Situationists rejected authority and backed the 1968 student uprising.

Numerous non-Leninist left alternatives have emerged over the years, but so far they have failed to create enduring movements.

An obvious but important point in looking to the future is the need to think strategically and avoid moralising.

Pluralism is vital. There are no predetermined solutions and we have to be open to the possibility of being wrong.

Too much left politics uses slogans to score points over rival organisations, rather than planning how to take on the powers that be.

And if we don’t think strategically we risk repeating doing what we have always done because we are comfortable with the familiar.

Some political parties have traditions of fighting local elections using community politics, others sell newspapers and organise marches.

But we need to question what we do, asking whether the tools for change need to be reshaped if they are to be suitable for the task at hand.

Too often disillusionment leads to the loss of activists. How do we attract more individuals to socialist activism and deepen their capacity?

Political participation is more likely if it is enjoyable. Theory is essential, but being “correct” is often less important in the first instance than promoting participation.

So a flexible, experimental approach to left politics is necessary.

I am often criticised for being a member of the Green Party. Haven’t Green Parties in Ireland and Germany sold out? Indeed they have.

However from our excellent MP Caroline Lucas to the work of our new leader Natalie Bennett and our new deputy, the ecosocialist activist Will Duckworth, I am proud to be a Green Party of England & Wales member.

Yet Greens have a long way to go to transform British society and the danger of losing our radicalism must never be ignored.

To guard against this, I feel a Marxist analysis is essential. Activists in inspiring movements like Occupy often reject the need to debate the words of long-dead revolutionaries.

Yet class struggle shapes society. We have an economic system of capitalism that oppresses humanity and degrades the environment.

The forces of capital are immensely strong in Britain, from media control to the power of the City of London to patterns of land ownership that would make an old-school central American dictator blush.

And these forces tend to distort what we do on the left. As Marx noted, when we “make history” we do not do so “in circumstances of our own choosing.”

However we shouldn’t focus only Marx and Engels and our favourite theorists. Marx learned from those whom he criticised – even Proudhon and Adam Smith – and used them to develop his thinking.

We should learn positively and negatively from others. I don’t see enough organisations on the left quoting Paulo Freire or Thomas Sankara or anti-imperialists such as Franz Fanon or liberation theologists. We need to keep thinking further and learning more.

The attitude of if you lose a battle, give up and cry betrayal, always seems wrong to me. Neither must we celebrate the defeat of others on the left. Raymond Williams, the literary critic and socialist, famously proclaimed: “No enemies on the left.”

If Greens fail that doesn’t help the Labour left, if other socialist parties fail or move through crisis, that doesn’t help Greens. Discord, defeat and disillusionment must be squarely addressed and resisted.

Which takes us back to Beckett. His absurdist plays had nothing to do with engaged politics. He never wrote on socialist theory or practice. But when the call came he answered it decisively and effectively.

Living in Paris in the 1940s, he saw his friends being rounded up by the nazis and the right-wing Vichy regime.

He joined the French resistance and worked for their victory, in later years modestly dismissing his contribution as “boy scout stuff.”

It is easy to lose faith on the British left, but our circumstances, however discouraging, are rather gentler than Beckett’s.

Not only can we fail better but if we organise strategically we can win.

All human organisations need a hierarchical structure in order to function effectively but what they do not need is for the ultimate decision making power to be passed up the hierarchy. As far as I know this is the unthinking practice of all organisations bar those of Quaker. Amongst Quakers ultimate decision making power is never ever passed up the organisational hierarchy it always remains firmly at the bottom most level where all the members are.

An interesting post, but in Bristol certain socialists on the left, particularly some in the Socialist Party and Socialist Equality Party, seem determined to vindictively attack the Green Party at every opportunity. That doesn’t help!