The debate following our article in Grist reveals that many greens have a blindspot about class. Blaming the world’s problems on too many people makes little sense when one-half of one percent of the world’s population owns nearly 40% of all wealth and controls most of the rest

by Ian Angus

This week, the environmental website site Grist published an article by Simon Butler and me, Is the environmental crisis caused by the 7 billion or the 1%? This was a departure for Grist, which frequently carries articles warning of an impending overpopulation apocalypse. Kudos to editor Lysa Hymas for commissioning and publishing an article I’m sure she doesn’t agree with, in order to promote discussion of this important issue.

The article was posted on Wednesday, Oct. 26, and by Friday 820 people had “liked” it on Facebook, making it one of the three most liked articles in Grist‘s Population section this year. [Update, Nov. 1: Now over 1,000 likes.]

But judging by the comments it received, some readers are less than keen about any discussion that focuses on issues of class, power, and inequality. One wrote:

“What a piece of leftist drivel. I don’t need to say this because most of the other commentors already have, but this crap is another low point for Grist.”

The most frequent criticism from Grist commenters accuses us of failing to understand that consumer desires drive the economy, that corporations are just responding to our demands, expressed through the market. The system isn’t at fault, “we” are.

Some examples:

“Billionaires aren’t mining and pillaging for their own enjoyment – almost all of us in developed nations use those resources every day.”

“The 1% may own the companies and wealth, but that wealth comes from selling us all stuff, and it is hypocritical to say that all of us have not invested something in the global economic system. ”

“Less consumers equals less demand equals less consumption equals less sprawl equals less congestion equals less garbage equals less need for fossil fuels. Grist is on the wrong side of this issue.”

“But BP could not have polluted the Gulf Coast if there was no demand for petroleum. The demands of those 7 billion are driving corporations to fulfill the demands of all the humans inhabiting this planet. After all, if we were at say 3 billion now BP would not have had to drill in the Gulf in the first place.”

I responded to these comments with a brief summary of arguments that Simon and I make in Chapter 12 of Too Many People?

That view, known to academic economists as “consumer sovereignty,” suffers from at least four fatal weaknesses.

“First, it ignores the immense market power of the wealthiest consumers. In the U.S., the richest one percent have greater wealth than the bottom 90 percent combined. The poorest 50% collectively own just 2.5% of all U.S. wealth. Analysts at Citibank have used the term ‘plutonomy” to describe the economies of the U.S., Canada, U.K., Australia, and others, which are dominated “rich consumers, few in number, but disproportionate in the gigantic slice of income and consumption they take.”

“Second, it ignores the fact that markets aren’t just unbalanced in favor of rich buyers, they are consciously manipulated by rich sellers. The 1% aren’t just richer, they have the power to engage in what John Kenneth Galbraith called “management of demand” – far from just responding to consumer demand, corporations actively create demand for the products they find most profitable to sell.

“Third, it ignores the fact the range of choices available to buyers is determined not by what is environmentally friendly, but by what can be sold profitably. As a result, we get microchoices such as Ford vs Hyundai — but not real choices such as automobiles vs reliable and affordable public transit.

“Fourth, it ignores the fact that buyers have little or no influence over how products are made or produced. BPs decision to ignore safe drilling practices in the Gulf, Shell’s decision to dump oil in the Niger –those decisions were made not by consumers but by corporate executives, to maximize the profits demanded by their shareholders. And remember – 1% of the population owns a majority of stocks.

“In short, the 1%, not the 7 Billion, control what is sold and how it is produced.”

The underlying problem with the discussion, I think, is that many Grist readers – certainly the ones that are unhappy with what we wrote – are blind to class. They know that the 1% do more environmental damage than the rest of us, but view it as just a matter of degree, not as a fundamental class divide.

In fact, to echo F. Scott Fitzgerald, the very rich are different from you and me. As we wrote in Too Many People? they don’t just have more money:

“At some point near the top of the income ladder, quantitative increases in income lead to qualitative changes in social power, exercised not through consumption but through ownership and control of profit-making institutions.”

The Grist commenter who wrote that we all damage the environment, “the rich are just more destructive,” seems to be unaware of just how vast a gap there is between the very wealthy and the rest of us.

Perhaps this will clarify matters for greens who don’t trust what two leftists have to say. Last week, the decidedly non-socialist investment bank Credit Suisse issued its annual Global Wealth Report. Its main conclusion was reported by the decidedly non-socialist Wall Street Journal.

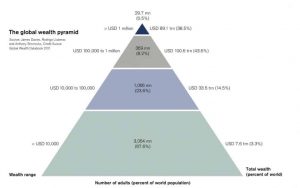

“Here’s another stat that the Occupy Wall Streeters can hoist on their placards: The world’s millionaires and billionaires now control 38.5% of the world’s wealth. … the 29.7 million people in the world with household net worths of $1 million (representing less than 1% of the world’s population) control about $89 trillion of the world’s wealth.”

This Credit Suisse graphic gives some idea of how unequally global wealth is distributed. (Click for larger image)

Economics professor David Ruccio comments in the Real-World Economics Review blog:

“the figures for mid-2011 indicate that 29.7 million adults, about 1/2 of one percent of the world’s population, own more than one third of global household wealth. Of this group, they estimate that 85,000 individuals are worth more than $50 million, 29,000 are worth more than $100 million, and 2,700 have assets above $500 million.

“Compare this to the bottom of the pyramid: 3.054 billion people, 67.6 percent of the world’s population, with assets of less than $10,000, who own a mere 3.3 percent of the world’s wealth.

“Add another billion people with assets between $10,000 and $100,000 and we have 91.2 percent of the world’s population that owns something on the order of 17.8 percent of total world wealth.”

He could have added that most of the wealth held by the bottom 90% consists of family homes, while richest 1% own most corporate shares. The rich aren’t just richer — they own wealth that gives them control of our economic system, and they profit from environmental destruction.

Reducing human numbers might, over many decades, make a small difference to the global environment. Eliminating the wealth and power of the 1% is the only way to completely turn things around.

+++++++++++++++

“The one per cent who have half the wealth don’t eat half the food, so the outrageous maldistribution of wealth in the world is in context a red herring.” Nicholas C. Arguimbau

I’m not sure what that has to do with anything. I do think we need to get away from scapegoating any particular number of people when the problem is caused in varying degrees and different ways by a range of people on a complex continuum of differentiated responsibility. A very large part of it is caused by us. A tiny percent (.1? 1? 13?) have control over far more than their share of the food, land, income, wealth, resources of all kinds. They decide what happens to those—whether they’re “allowed “to be natural, used for subsistence food, luxury food (meat, e.g.) 4th houses, mining, ocean dead zones… etc. So they do “eat half the food”. The richest half emit 93% of the greenhouse gases and cause a similar proportion of most ecological problems. The richest 20% cause about 80% of those problems. The developed world’s human population is essentially at replacement rate, not counting immigration (which is largely caused by the exploitive policies of those same countries and their people, through the tools of corporations). The rest of the human population is slowing its growth and with a reasonable effort we could soon bring it to a stable number. The ways to do that—free access to birth control and family planning, security for all in age, sickness and hard times, education and empowerment of all, especially women, and above all, equality and a re-configured economic system, are blocked by the richest in the US above all others.

No one dies of overpopulation. Someday, if we survive another hundred years and current declines in population growth are reversed then some people may starve because of overpopulation. Except no, because carrying capacity is being reduced by changes caused by the consumption of the rich. For example, climate change-caused Himalayan glacier melt threatens a billion people’s food and water. Right now, every country in the world produces enough food for its people, and even during famines local elites have plenty and luxury foods, industrial process foods (soy, corn, palm oil…) and livestock feed are exported. The problems most associated with overpopulation are almost always caused by other factors and very slightly exacerbated by high or growing population. African famine, for example, is caused mostly by a shift in Indian Ocean monsoons, caused by climate change, caused by the rich.

Our most dire problem is climate catastrophe. We have to reduce greenhouse gas emissions about 90% in the next 10-20 years at most. (See the recent IEA report for an even more urgent view) What if we try to do that using population means? Imagine the most successful possible birth control program possible: no children born in the world for 20 years. (an unimaginable demographic disaster on its own but let’s ignore that for now) Our population would decline from 7 billion to……6.9 billion. Since rich populations aren’t growing anyway and make up such a tiny percent of the total, the vast majority of that decline would be among the people who contribute least to the problems. So no solution there. So what is the solution? Death control? What number of people do you think is right? 2 billion? How do you propose to kill more than 5 billion people without racism, nationalism, and all the other prejudices people use to project and scapegoat others? IOW, how do you propose to do it without the most desperate, destructive, carbon-intensive wars ever fought?

Saying we should have done this or that about population 30 years ago is useless. I’ve been fighting for solar and wind, appropriate technology, efficiency, more ecological, considered lives, for 30 years too. If we had done all those we’d have a different world now too, one with no climate problem. We didn’t. We have what we have now and have to proceed from here, not some imaginary world.

The idea that there’s some massive conspiracy about discussing population is absurd; it’s one of the few ecological problems that virtually every educated person in the world knows of. It’s talked about constantly, thus promoting the (mostly unconscious) idea that overwhelming numbers of dark people are threatening to overrun the rich people of (mostly) white who are the actual cause of the problem. The result of that is that the very rich continue to be allowed to delay the real solutions: efficiency; solar; wind; local organic permaculture; reforestation; biomimicry in industry; meat in the diet only where ecologically appropriate (short grass prairies, circumpolar regions, and in small-scale permaculture systems that remove the disproportionately high cost of meat production as it’s currently practiced.); redesign of human settlement patterns to encourage walking, biking, and mass transit; rail, sail, mail (deprivatization) and scale (small)… and political and economic transformation to achieve a rational, ecological society based on personal rather than economic growth.

perhaps if we eliminate industrial civilization, the globalized market and those 90,000 odd top wealthiest people who are responsible we have a good starting point?

Marion Delgado demonstrates that “mentioning class” isn’t the same as understanding it. What he calls “science” is precisely an attempt to direct attention away from class to the simplistic body-counting of populationism.

In a comment following our article on Grist, Delgado says that Paul Ehrlich was “mostly right” in The Population Bomb, a 1968 book whose theme was “the battle to feed humanity is over.” It predicted a huge increase in the death rate in the 1970s. The global death rate in 1970 was 13.2 — it is now 8.3.

As for our supposed “cornucopian denialism,” I hope he will read our critique of Julian Simon and others of his ilk, in chapter 4 of Too Many People?

I love mentioning class. But you’re scientifically off base. Moreover, your trope is exactly the one the 1% wants you to spread. You’re doing their work for free. Cornucopian denialism is not a plus here. Julian Simon and John Tierney and John Stossel are applauding you and not the people who understand what the 1% have done to the population, consumption and resource debate.

This came to me late, but is the best debate I have ever witnessed. Thank all for contributing, I feel this debate can do more to unite than divide.

The debate about how to share the cake and how many mouths there are isn’t either or; it’s and.

I agree with this note. Grist’s readers are class blind because most of them are among privileged classes (as in, just for being a US / European citizen) with enough time and access to post on Internet forums (in English, which leads to think they probably don’t know other languages, as most US citizens happen to lack) and earning more than most world inhabitants even if they have medium or low income for their developed countries.

Either way, given that their consumption rates are impressive on their own, having them think consumption is the problem is not that bad at all. They are great consumers at that. If they think population is the problem, that’s not bad at all because having one less US / European baby means a new BIG consumer is avoided. So it works either way! Less of them or less of what they do works just fine!

Have we exceeded the carrying capacity of our planet with a combination of 7 billion people, together with our feverish resource squandering?

Absolutely.

But population growth is linked to insecurity. If we had a world of equity, security and material sufficiency, the population would stabilize much faster, under its own steam. And the human burden on the planet’s resources would shrink even faster still.

Surely it is better to lean our shoulders to that task, rather than squirming around trying to shave millions off the population by enforced population controls?

Nicholas C. Arguimbau says that if the Green Revolution hadn’t occurred then Ehrlich would have been right. So, the problem is not with the predictions but with reality.

Now, if only we could find a way to make reality fit with populationists’ models…

Nicholas C. Arguimbau informs us that if the so-called Green Revolution hadn’t happened, a billion people would have starved to death. That’s undoubtedly true, but it doesn’t prove that dropping population control from the environmental agenda was a devastating and cowardly mistake. That’s just another way of expressing the fallacy that the world food crisis itself is caused by people having too many babies.

Arguimbau never explains what exactly the environmental movement ought to have been doing – but wasn’t – to quell Borlaug’s “population monster” over the last 30 years. His article in Countercurrents talks about the need to “avoid gasohol and beef”, “manage and conserve our diminishing water supplies”, work to eliminate “abject poverty”, and limit ourselves to one child per family. It seems to me, however, that the environmental movement has had very much indeed to say in the last 30 years about how biofuels aggravate the food crisis; how industrialized agriculture has rendered livestock production unsustainable; and how water supplies must be preserved, managed, and regulated. And I don’t know of any responsible person – inside or outside the environmental movement – who is opposed to eliminating “abject poverty”. As for one child per family, is Arguimbau unaware of the experiences of China and India with coercive population control? Is that a policy the environmental movement should have been championing for the last 30 years? Apart from fringe elements like Earth First, was this kind of “population control” ever even on the environmental movement’s agenda to begin with?

The fact is that the “Green Revolution” was not the only thing that foiled Ehrlich’s dire predictions. Birth rates actually fell – without “population control” – and in fact were already falling in the most developed countries before Paul and Anne Ehrlich wrote The Population Bomb, began advocating for compulsory sterilization programs in poor countries, and urged the U.S. government to withhold foreign aid from countries with expanding populations unless those countries made major efforts to limit their population numbers.

Finally, there is good authority to suggest that the capitalist class – the 1% – does not require continuous population growth to sustain its source of wealth. The 1972 Rockefeller Commission on Population Growth reported to President Richard Nixon:

I watched population control disappear from the environental agenda after the Green Revolution temporarily “proved Ehrlich wrong.” That was almost certainly the worst thing the environmental movement ever did. It was devastating, and it was cowardly.

Without the Green Revolution, Ehrlich wold have been abolutely right. Global famines were looming, largely as a result of enormous improvements in medicine without corresponding changes in agricultural practices, resulting in an unsupportable population boom. The Green Revolution was a temporary techno-fix. Its primary strategies were increased artificial irrigation and increased use of nitrogen fertilizer. The former is now running its course because the world is facing overdrawn aquifers in all major grain-poducing areas – India, China and the US particularly. The latter is running its course because nitrogen fertilizer requires enormous fossil-fuel inputs, and the day of plentiful inexpensive fossil fuels is over.

Norman Borlaug, father of the Green Revolution, faced the looming dieoff of half a billion people with a temporary solution that saved their lives. In his Nobel lecture he said it was a temporary fix – that the Green Revolution had given the world a 30-year reprieve from the “population monster,” but if tha time was not devoted to bringing population under control, there would be disaster.

We did not heed his words but did the opposite. The thirty years were squandered. Now the collapse of oil, the collapse of aquifers, with them the collapse of the Green Revolution itself, are leaving us without options, and thanks to our failure to heed Borlaug’s words, now we have nearly twice the population to feed. Grain production per capita has been decreasing for 25 years and 1 billion people already go hungr; there is no known techno-fix out there to change this, only the techno-fix of the Green Revolution about to be undone.

The one per cent who have half the wealth don’t eat half the food, so the outrageous maldistribution of wealth in the world is in context a red herring. Indeed, there is a great irony in posing the question of whether our environmental problems stem from the 7 billion “or” the one per cent. The latter are the capitalist class. They got where they are through a capitalist system that demands more than anything, “economic growth.” Economic growth has two primary ingredients – exloitation of under-priced natural resources, and population growth. How do you think they can go on selling more widgets if there aren’t more natural resources to make them with and from,and more people to sell them to? So are the 1% going to favor an increase or a decrease of the population? Increase, of course. Increase without end.

Rather than heeding Borlaug’s words about control of the “population monster” – he could as well have said “population bomb” – the environmental movement moved into a conspiracy of silence over population. The leaders who had spoken eloquently in the seventies about population being the ultimate environmental issue, commenced to look at everything but population. The primary reason for this was direct or indirect, conscious or unconscious, subservience to the 1%.

The programs of nonprofits are largely dictated by foundations from which they seek funding – outlets for the charitable urgings of the 1 per cent. They may be charitable, but will they cut their own throats, supporting programs to cut the source of their wealth? No, and they do not. Even the smaller foundations with srong liberal leanings are themselves funded by the stock market – funded, in short, by economic growth. The fact is that advocacy of population control is very difficult to fund.

So, when the 1% hear arguments that they, “not” population, are the problem, they can trot happily off to the bank, giggling as they go as to how they have conned leftists into helping them line their pockets.

The “class” and “race” arguments are particularly insidious Somehow a large segment of the left has been conned into believing that population control is an attack on the “lower class” and on “racial minoritieswith high fertility rates. This is dead wrong. Those are the beneficiaries of population control, and the 1% are those who are hurt.

Whether there is a population problem or not needs to be looked at objectively, rather than ideologically. Food provision is one of the many issues related to population that can be looked at objectively, and I made an attempt to do so last year in “Peak Food: Can Another Green Revolution Save Us?”. http://www.countercurrents.org/arguimbau310710.htm. Since that article, the problem has become more acute by (1) American diversion of 40% of its corn (6% of te world grain supply) to ethanol for its inasatiable automobiles, (2) EU’s adoption of a policy for diversion of 17% of its grain land for the same purpose, (3) China’s leaning toward a program of depleting the North China Plain’s population to feed its growth engines and solve its water problems, simultaneously becoming a major grain importer, (4)diversion of grain to increased meat production in Asia as their populations become wealthier, (5) climate instability causing crop failures around the world, and (6)peak oil causing rapidly rising oil prices (FAO issued a report in 2010 predicting we could get through the decade without failure of the food system, assuming theere would be no oil shortages or prices above $90 per barrel; how likely is that when the price hovers around $110 already?).

Is there a population problem? Of course there is a population problem, and the 1% aggravate it.

Nicholas C. Arguimbau narguimbau@earthlink.net

For the discussion on ‘consumer sovereignty’ income figures may be more appropriate than wealth. An impecable source here is the World Bank chief economist Branko Milanovic’s work on income inequality among individuals in the world as opposed to country averages e.g., see his 2007 book: http://press.princeton.edu/titles/7946.html or this Youtube clip http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SMsirg7Z0bU