INTERVIEW: How laborers, sharecroppers, and tenant farmers have united to block construction of the giant El Quimbo Dam, a multinational project that would destroy the homes and livelihoods of hundreds of peasant families in southern Colombia.

Every year the U.S.-based Colombian Human Rights Network (Red Colombiana de derechos Humanos, CHRN) sponsors a tour of human rights activists from Colombia. Their aim is to develop lobbying and education strategies to address human rights issues there.

This year the Network invited Miller Dussán Calderón, professor at the University of South Colombia (Universidad Surcolombiana) from the city of Neiva, in the Department of Huila. His tour has focused on spreading information about the resistance being carried out by communities affected by a network of dams, which are to be constructed by foreign companies. Calderón spoke as legal representative of ASOQUIMBO, the Association of Persons Affected by Quimbo’s Hydroelectric Project (ASOQUIMBO).

He was interviewed for Climate & Capitalism by Gabriel Chaves and Germaine Gagnon, in New York City on September 25.

Miller Dussán Calderón

Q: Please share something about yourself, and how the ASOQUIMBO movement was born.

A: As a professor I have worked in the fields of philosophy, pedagogy, epistemology and conflict resolution. I am a linguist at the University of South Colombia. I also have a speciality in political and legal institutions from the National University of Colombia, as well as a doctorate in Education and Society from the Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain. In Colombia I participate in the construction of the ecosocialist movement.

ASOQUIMBO was formed 4 years ago in response to violations of economic, social and cultural rights of the communities affected by the Quimbo dam project. ASOQUIMBO was born of the need to defend the land. The most critical problem that currently faces Latin America is corporate land control by multinational firms. We seek to defend the land, and this implies defending our genetic and cultural diversity, our rivers and our communities from these harmful energy, mining and biofuel mega-projects.

Q: Please speak to the history and agenda of the hydroelectric industry in Colombia and Quimbo’s position within this project.

A: Quimbo is part of a regional plan called Initiative for the Integration of South American Regional Infrastructure, or IIRSA in Spanish (Iniciativa para la Integración de la Infraestructura Regional Suramericana), which seeks to integrate South American infrastructure with extraction plans financed by multinational capital. Extensive exploitation of minerals such as gold and coltan (columbite–tantalite), energy and biofuels are being planned.

Using the National Council for Social and Economic Policy, our former president, Alvaro Uribe, approved the IIRSA plan. It includes 4 dams: Ituango in Antioquia, (2400 megawatts), Sogamoso in Santander (800 megawatts), and Quimbo (400 megawatts) close to dam of Betania (~520 megawatts) in Huila.

There are also open-pit mining projects such as La Colosa in Tolima, and Santurbán in Santander destroying mountains, rivers and requiring much water. These projects are supported by businesses that follow the Canadian model of open-pit mining, such as Anglo-Gold Ashanti. The energy that will be produced is intended for export and to supply mega mining projects. Colombia currently produces 50% more energy than it consumes domestically. The state claims that it is taking advantage of its hydro resources to transform Colombia into a hydroelectric power.

Q: Tell us about the the community surrounding the dam, its history and who will suffer if it is built.

A: Initially, the movement started with 50 persons, including the very poor – day laborers, squatters and small land owners. Most of the population is mestizo and lives in areas which previously were occupied by indigenous people who were displaced. They’ve created community businesses as a result of agrarian reforms in the 1960s. They are day laborers, sharecroppers or majordomos, who farm land owned by others.

92% of the land belongs to 12 families, while 8% belongs to 300 families. The company believes that by buying only from the richest families it will gain control of the area to be flooded, and it ignores the needs of the 300 families of small plot land wonders. ASOQUIMBO’s base is the 300 families and 2 of the big landowners. The other 10 big landowners sold their lands quickly to the company.

Over time a crisis has grown affecting the very poor in other sectors of the economy. For example, when growers stopped producing, they no longer purchased supplies from big sellers. And the sellers who previously supported the project for its positive development discovered that their own livelihood was threatened. Some among the wealthy are now allying themselves with ASOQUIMBO.

Q: Which multinationals currently control the Quimbo dam? Describe their relationship with the government and with the surrounding communities.

A: The project was authorized by ex-President Uribe as a grant to Emgesa (Spain); later the majority of the shares were sold to Enel (Italy), even though Emgesa still managed the administrative portion. The dam is to be used for one purpose only, which means that it will not be used for other activities, such as fishing.

The government’s motivation follows from the belief that a country’s economic growth is determined largely by foreign investment and that economic growth results in greater social equity. We do not agree: these mega-projects are, first and above all, for the sake of the corporations involved. The government grants businesses full powers against communities.

Starting with the already existing natural wealth commanded by the river, building a dam is a simple task from an engineering point of view; the winding terrain aids in confining the water. This means that the cost of constructing a dam is very low for investors, but for those it impacts it is among the costliest forms of energy. Dams damage the environment and social networks. They displace more people than wars.

Another advantage for the companies is that the government has adjusted the national laws to suit their needs: foreign companies pay lower taxes than individuals in Colombia. In the past, land was loaned for fixed periods of time, now grants exist into perpetuity and this area will not return to Colombians. Laws governing workers has been watered down, permitting companies to subcontract in violation of the workers’ rights. Who wouldn’t invest under these conditions? This is what the government calls “investor confidence.”

The government also created a mechanism called a “reliability charge” to promote investment. Companies are able to play the stock market while it is not generating energy, and the government pays a security for 20 years from the state treasury. This is done in return for the company giving priority to the national government in event of energy scarcity, a remote possibility. There are no legal requirements whatsoever requiring that the company profits be reinvested domestically.

Another important stimulus to investment is what the government calls “democratic security.” To prevent the guerrillas from interfering in construction, They’ve opened a military base named “Energetics Battalion #12.” According to the Defense Ministry, it has 1,200 troops and costs Colombia $74 million dollars annually. Colombian citizens end up paying for the business’s security expenses.

Also, the company speaks of a “legal guarantee” whereby it requires that the environmental permit can never be modified, even by the subsequent governments. It’s a way for foreign companies to demand legal guarantees and shielded themselves from their legal responsibilities. For these new capital investments the state has ceased to guarantee the rights of its citizens and is transforming itself into a middleman for the markets. Peasants become objects of the market.

Colombian law requires that if land use changes, there must be a popular referendum. Quimbo’s territory is for agricultural production. In order to dedicate it to dam use, the government should have consulted the communities. No referendum was held based on the argument that the production of energy is of national importance. The problem is that the production of food is also of national importance, and the government prefers private, foreign companies to the people of Colombia.

More serious still, the company is supposed to restore the productive labor of the persons who work in the areas that will be flooded. The Colombian state permitted the company to change its development plans for the municipalities that border the dam without any authorization from the affected communities. While the company decides how to manage the territory, citizens lose sovereignty.

Finally, in order to restitute land to persons affected by the Quimbo dam, the company picks other, already inhabited lands, and then displaces the inhabitants so that these other lands can be used as restitution for the people affected by the Quimbo dam: this creates a chain of displacements.

Q: You are in a legal dispute with Emgesa. What is it based on?

The Attorney General’s office petitioned the National Authority of Environmental Licenses (In Spanish, Autoridad Nacional de Licencias Ambientales, ANLA), to deny Emgesa a license, because it did not observe Congressional laws meant to preserve the Amazon basin, warning that the Department of Huila will undergo soil desertification and food insecurity. The Uribe government ignored the petition from the Attorney General’s office. Six days later it approved the environmental license. The communities surrounding the dam and the Attorney General’s Office requested that the government halt the project, but Uribe said that he would not back down because he did not want to lower investor confidence.

Q: Miller, what is the history of resistance against Quimbo? How is it spreading to other regions?

A: Initially, there was opposition from politicians and economic associations, but Uribe bought them off. On the government’s side are multinationals along with local and national politicians. The only group that has resisted is ASOQUIMBO.

The first step of the resistance was a series of studies of the impact of the dam. We studied the company’s proposal closely. Our investigation was done with the participation of the community, who helped compile and analyze the relevant documents. We had to refute the company’s propaganda and show that their model of intensive extraction is incompatible with social responsibility and environmental sustainability.

Our movement is one of civil resistance, which distinguishes it from the existing armed movements. We believe that communities should exercise control over the land. For us democracy consists of being able to control the communities in which we live. Control should not be in the hands of the guerrillas or the government.

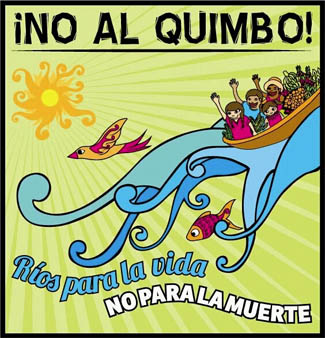

Because of our work on Quimbo, we were invited to Santander and Antioquía. Based on this, we launched a national movement called Ríos Vivos (Living Rivers) to coordinate the actions of all the movements. We have legal strategies in addition to mobilizing the citizenry. The government has acted repressively and has been chided internationally for its disproportional use of force.

As a result of our initial activism and research, ASOQUIMBO was invited to meet with the Controller’s Office (Contraloría). The Controller’s Office supported our findings; that damages caused by construction have already surpassed what the company is slated to pay in total for the social and environmental costs of the project overall. The Controller’s Office petitioned the Accounting Office (fiscalía) to open a legal investigation against the Environmental License Authority, saying the project was not illegally approved since no serious, scientific study was done.

Q: How has the government responded to the Accounting Office’s investigations?

A: In order to protect itself, the Ministry of the Environment (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente), allied itself with the Emgesa. It modified the licenses on multiple occasions in order to free the company from legal obligations. Many in the Ministry of the Environment have previously worked for energy companies. There’s a revolving door between the companies and the regulating institutions.

We believe that the Controller’s Office takes us seriously. Our problem is that the Controller’s Office is unable to suspend the license despite the fact that it is behind our demands. The only agency that can suspend the license is the Ministry of the Environment. The Ministry will not suspend the license, because it doesn’t want to admit wrongdoing. The only avenue left to us is the State Council (Consejo de Estado), where an application can take 10 years or more before finding support. Therefore we are applying pressure through social mobilizations to accelerate the legal process.

Q: How strong is the resistance? What actions have been organized?

A: The local economy has deteriorated as the business occupation’s effects in the region have made themselves felt. Today, 12,000 people have been affected by the Quimbo project. Emgesa wishes to move the river away from the fishermen, because the company claims the river above and below the dam in order to guarantee the production of 1000 megawatts of energy between Betania and El Quimbo. The company still has not reimbursed the people affected by the Betanía dam, which was built earlier, but it wishes to control the river because the Quimbo dam increases the energy output of Betanía.

The campesinos and other persons displaced by Quimbo decided to return to the estates where they previously worked. They obtained seeds and have had two successful harvests. At this moment, Emgesa wishes to evict them and has police resources at its disposal to violently displace the campesinos. The threat is real.

In the urban areas of Huila, links have been established between organizations such as The Central Workers Hub (La Central Unitaria de Trabajadores) and the Union Association of University Professors (la Asociación Sindical de Profesores Universitarios). Elsewhere in the country there are CENSAT Agua Viva and Planeta Paz.

As for student support, the solidarity of the students of the Universidad Surcolombiana (University of Southern Colombia) has been very significant, particularly for its presence in the social mobilizations in urban Neiva, as well as in the Quimbo zone.

ASOQUIMBO has decided to recover more, preferably all, the lost lands. On October 12, we will have an international congress and we will occupy all the ceded properties: those to be flooded and those that have been purchased for the restitution of productive activity. We have the support of indigenous groups to recover and seize land from the company in the area. We will build a Campesino Reserve Zone (Zona de Reserva Campesina) administered by the poor of the countryside.

We are touring the United States in an effort to gain international support for our October mobilization to recover the land. Among the countries where allies have confirmed their support are: Spain, Italy, Brazil, Chile, Guatemala. We are requesting actions of international solidarity beheld for our land recovery. We want the multinationals to leave our land.

The Colombian Human Rights Network (Red Colombiana de Derechos Humanos) is made up of the Colombian Human Rights Committee in Washington D.C., the Movement for Peace in Colombia in New York, and Colombia Vive in Boston. To obtain more information, email: chrn@googlegroups.com. Miller Dussán blogs at: http://millerdussan.blogia.com/.