Cyclone devastates Chennai, India, December 5, 2023.

From a report published this month by the magazine Down To Earth and the Centre for Science and Environment.

by Kiran Pandey and Rajit Sengupta

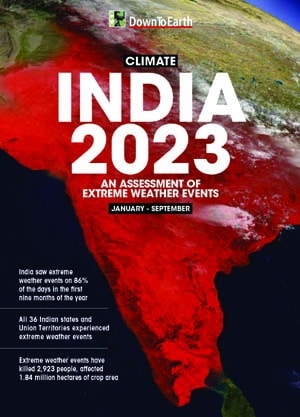

India recorded extreme weather events on 235 of the 273 days from January 1 to September 30, 2023. This means that in 86 per cent of the first nine months of this year, India had an extreme weather event breaking in one or more parts of the country. It also experienced record-breaking temperatures for several months, and regions across the country were deluged because of very heavy and extremely heavy rainfall. This led to floods and the loss of life and livestock. This speaks of the increased frequency and intensity of the extreme events that we are seeing in our rapidly warming world. …

India has seen a disaster nearly every day in the first nine months of this year-from heat and cold waves, cyclones and lightning to heavy rain, floods and landslides. These disasters have claimed 2,923 human lives, affected 1.84 million hectares (ha) of crop area, destroyed over 80,563 houses and killed close to 92,519 livestock. This calculation of loss and damage is probably an underestimate as data for each event is not collated, nor are the losses of public property or crop calculated.

With an event every second day, Madhya Pradesh saw the highest number of days with extreme weather events; but Bihar saw the highest number of human deaths at 642, followed by Himachal Pradesh (365 deaths) and Uttar Pradesh (341 deaths). Himachal Pradesh reported the highest number of damaged houses (15,407) and Punjab reported the highest number of animal deaths (63,649).

Madhya Pradesh has experienced an extreme weather event on 138 days since the beginning of 2023. Despite this, official records indicate no crop area damage. However, media reports suggest that at least 45,000 hectares of crop area were affected. This discrepancy could be due to gaps in loss and damage reporting.

While January remained slightly warmer than average (1981-2010), February exceeded all previous records to become the warmest in 122 years. Northwest India was especially hot, with a 2.78oC temperature anomaly above average (1981-2010). March was modestly warmer for India once again, however, the average minimum temperature in Northwest India was 1.34oC above usual. The country’s mean temperature stayed near average in April and May, with the exception of the South Peninsula, which had the third highest average maximum temperature for April, with an anomaly of 0.77oC. This June was the sixth warmest on record for the country, with the South Peninsula reporting its warmest June on record. In July, the country had its second-warmest minimum temperature in 122 years. August and September were again the warmest ever for the country.

India also recorded its sixth driest February and its driest ever August in 122 years. Meanwhile, March remained unusually wet for Central India and the South Peninsula, with the two regions receiving 206 per cent and 107 per cent of the long-term average (1971-2020) rainfall, respectively.

This is the watermark of climate change. It is not about the single event but about the increased frequency of the events-an extreme event we saw once every 100 years has now begun to occur every five years or less. Worse, it is now all coming together-each month is breaking a new record. This, in turn, is breaking the backs of the poorest, who are worst impacted and are fast losing their capacities to cope with these recurring and frequent events.

In terms of the “nature” of the event, all types of extreme weather have been seen in the past nine months — lightning and storms were reported in all 36 states and Union Territories and claimed 711 lives. Then, every day of the three months of monsoon-from June to August-shows heavy to very heavy and extremely heavy rainfall in some parts of the country. This is why the flood devastation has not sparred any region-in Himachal Pradesh, for instance, vast parts of the state were submerged and people lost lives, homes and sources of livelihood.

This is why the extreme weather report card is important to understand. It tells us of the number of such events; the fact that this will lead to cumulative and extensive damage. And that fact that we need systems to better account for the losses so that climate change and its impact have the human face of their victim.

It speaks of the need to do much more to manage these extreme events-we have to move beyond the management of the disaster to reducing risks and improving resilience. This is why we need more than words to improve the systems for flood management-deliberately building drainage and water recharge systems on the one hand and investing in green spaces and forests so that these sponges of water can be revitalized for the coming storms.

This also speaks of the need to demand reparations for the damage from the countries that have contributed to the emissions in the atmosphere and are responsible for this damage. The models that explain the impacts of climate change are clear that extreme weather events will increase in frequency and intensity. This is what we are seeing today. This report card is not good news. But it needs to be read so that we understand the revenge of nature that we are witnessing today and also understand that it will get worse tomorrow if we do not combat climate change at the scale that is needed.