Source: American Geophysical Union

People with lower incomes are exposed to heat waves for longer periods of time compared to higher income people, due to a combination of location and access to heat adaptations like air conditioning. This inequality is expected to rise as temperatures increase, new research shows.

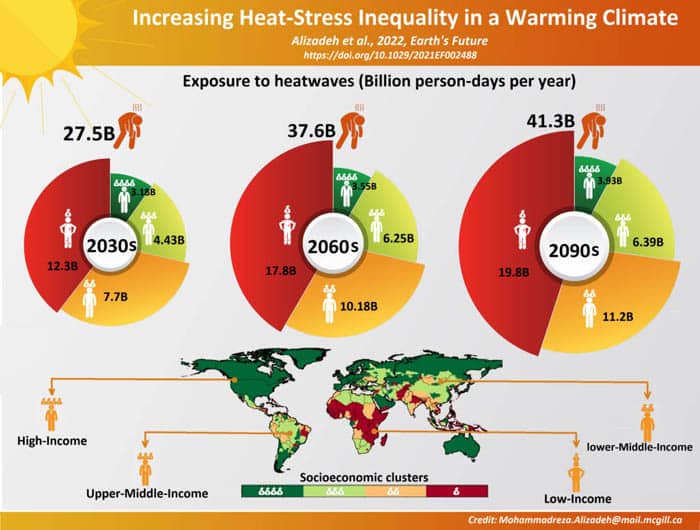

Lower income populations currently face a 40% higher exposure to heat waves than people with higher incomes. By the end of the century, the poorest 25% of the world’s population will be exposed to heat waves at a rate equivalent to the rest of the population combined.

Poorer populations may be hit with a one-two punch of more heat waves from climate change due to their location and an inability to keep up with it as a result of lack of heat adaptations like air conditioning.

The study analyzed historical income data, climate records and heat adaptations to quantify the level of heat wave exposure that people in different income levels face around the world. Exposure to heat waves was measured by the number of people exposed to heat waves times the number of heat wave days. Researchers paired those observations with climate models to predict how exposure will change over the next eight decades.

The study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Earth’s Future, on January 20. The researchers found the lowest-income quarter of the world’s population will face a pronounced increase in exposure to heat waves by 2100, even taking into account access to air conditioning, cool air shelters, safety regulations for outdoor workers and heat safety awareness campaigns. The highest-income quarter, comparatively, will experience little change in exposure as their ability to keep up with climate change is generally greater.

People in the lowest-income population quarter will face 23 more days of heat waves per year than those in the highest income quarters by 2100. Many populous, low-income regions are in the already-warm tropics, and their populations are expected to grow, contributing to the discrepancies in heat wave exposure.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence that populations who have contributed the least to anthropogenic climate change often bear the brunt of climate change impacts, said lead study author Mojtaba Sadegh, a climatologist at Boise State University. Historically, higher-income countries contribute a majority of greenhouse gases. “We expected to see a discrepancy, but seeing one quarter of the world facing as much exposure as the other three quarters combined… that was surprising.”

While higher-income regions often have greater access to adaptations, they will likely face rolling blackouts or brownouts as electricity demand swamps the grid. An increase in geographic area affected by heat waves, which the study found has already increased by 2.5 times since the 1980s, will limit our ability to “borrow” electricity from unaffected neighboring regions, like California importing electricity from the Pacific Northwest, Sadegh said.

“We know from far too much experience that issuing a heat wave forecast is insufficient to ensure that people know what appropriate actions they need to take during a heatwave and to do so,” said Kristie Ebi, a professor in the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the University of Washington who was not involved in the study. Collecting more data on heat wave frequency and responses in low-income countries, she said, is critical.

Sadegh hopes the study will prompt innovations into affordable, energy-efficient cooling solutions as well as highlight the need for short-term solutions. “We need to raise awareness of dangers and heat safety, and to improve early warning systems — and access to those early warning systems,” he said.

| Abstract of Increasing Heat-Stress Inequality in a Warming Climate by Mohammad Reza Alizadeh, John T. Abatzoglou, Jan F. Adamowski, Jeffrey P. Prestemon, Bhaskar Chittoori, Ata Akbari Asanjan, & Mojtaba Sadegh Earth’s Future, January 22, 2022 Adaptation is key to minimizing heatwaves’ societal burden; however, our understanding of adaptation capacity across the socioeconomic spectrum is incomplete. We demonstrate that observed heatwave trends in the past four decades were most pronounced in the lowest-quartile income region of the world resulting in >40% higher exposure from 2010 to 2019 compared to the highest-quartile income region. Lower-income regions have reduced adaptative capacity to warming, which compounds the impacts of higher heatwave exposure. We also show that individual contiguous heatwaves engulfed up to 2.5-fold larger areas in the recent decade (2010–2019) as compared to the 1980s.Widespread heatwaves can overwhelm the power grid and nullify the electricity dependent adaptation efforts, with significant implications even in regions with higher adaption capacity. Furthermore, we compare projected global heatwave exposure using per-capita gross domestic product as an indicator of adaptation capacity. Hypothesized rapid adaptation in high-income regions yields limited changes in heatwave exposure through the 21st century. By contrast, lagged adaptation in the lower-income region translates to escalating heatwave exposure and increased heat-stress inequality. The lowest-quartile income region is expected to experience 1.8- to 5-fold higher heatwave exposure than each higher income region from 2060 to 2069. This inequality escalates by the end of the century, with the lowest-quartile income region experiencing almost as much heatwave exposure as the three higher income regions combined from 2090 to 2099. Our results highlight the need for global investments in adaptation capabilities of low-income countries to avoid major climate-driven human disasters in the 21st century. |