Michael Roberts is a UK-based Marxist economist. His most recent book is Engels 200: His Contribution to Political Economy.

by Michael Roberts

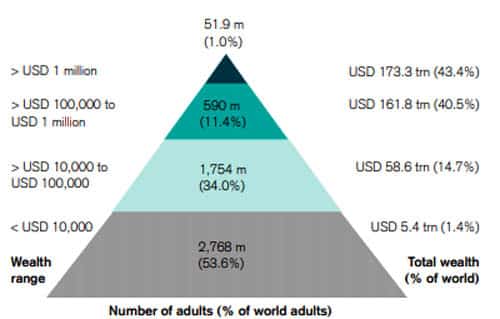

The top 1% of households globally own 43% of all personal wealth while the bottom 50% have only 1%. The 1% are all millionaires in net wealth (after debt) and there are 52m of them. Within this 1%, there are 175,000 ultra-wealthy people with over $50m in net wealth – that’s a minuscule number of people (less than 0.1%) owning 25% of the world’s wealth!

This information comes from the 2020 Credit Suisse Global Wealth report which has just been released. The report remains the most comprehensive and explanatory analysis of global wealth (not income) and of the inequality of personal wealth. Every year the CS global wealth report analyses the household wealth of 5.2 billion people across the globe. Household wealth is made up of the financial assets (stocks, bonds, cash, pension funds) and property (houses etc.) owned. And the report measures this, net of debt. The report’s authors are James Davies, Rodrigo Lluberas and Anthony Shorrocks. Professor Anthony Shorrocks was my university flatmate, where we both graduated in economics (although he has the much better mathematical skills!).

According to the 2020 report, total global household wealth rose by US$36.3 trillion during 2019. But the COVD-19 pandemic cut that 2019 increase by nearly half (US$17.5 trillion) between January and March 2020. However, because stock-markets and property prices then rebounded, thanks to government and central bank credit injections, the Credit Suisse researchers reckon that total household wealth was still slightly up by mid-2020 compared to the level at the end of last year, although wealth per adult was slightly down.

By mid-2020 global household wealth was US$1 trillion above the January level, a rise of 0.25%. As this is less than the rise in adult numbers over the same period, average global wealth fell by 0.4% to US$76,984. In comparison to what would have been expected before the COVID-19 outbreak, global wealth fell by US$7.2 trillion, or US$1,391 per adult worldwide.

The most adversely affected region was Latin America, where currency devaluations reinforced reductions in dollar GDPs, resulting in a 12.8% reduction in total wealth in dollar terms. The pandemic also eradicated the expected growth in North America and caused losses in every other region, except China and India. Among the major global economies, the United Kingdom has seen the biggest relative erosion of wealth.

Most shocking is the still huge inequality of household wealth globally. As shown by the wealth pyramid graphic below, inequality remains stark, both geographically between the ‘rich north’ and ‘poor south’; and between households within countries.

Global Wealth Pyramid at end of 2019

At the end of 2019, North America and Europe accounted for 55% of total global wealth, with only 17% of the world adult population. In contrast, the population share was three times larger than the wealth share in Latin America, four times the wealth share in India, and nearly ten times the wealth share in Africa.

Wealth differences within countries are even more pronounced. The top 1% of wealth holders in a country typically own 25%–40% of all wealth, and the top 10% usually account for 55%–75%. At the end of 2019, millionaires around the world – which number exactly 1% of the adult population – accounted for 43.4% of global net worth. In contrast, 54% of adults with wealth below US$10,000 (i.e. pretty much nothing) together mustered less than 2% of global wealth.

The researchers reckon that the worldwide impact on wealth distribution within countries has been remarkably small given the substantial pandemic-related GDP losses. Indeed, there is no firm evidence that the pandemic has systematically favored higher-wealth over lower-wealth groups or vice versa. In 2019, the number of millionaires worldwide soared to 51.9 million, but has changed very little overall during the first half of 2020.

At the apex of the wealth pyramid, the report estimates that at the start of this year there were 175,690 ultra-high net worth (UHNW) adults in the world with net worth exceeding US$50 million. The total number of UHNW adults rose by 16,760 (11%) in 2019, but 120 members were lost during the first half of 2020, leaving a net gain of 16,640 in UHNW membership since the start of 2019.

During the first half of 2020, the number of millionaires shrank by 56,000 overall, just 1% of the 5.7 million added in 2019. Membership has expanded in some countries and some have lost significant numbers. The United Kingdom (down 241,000), Brazil (down 116,000), Australia (down 83,000) and Canada (down 72,000) all shed more millionaires than the world as a whole.

It seems that wealth inequality declined within most countries during the early 2000s. The fall in inequality within countries was reinforced by a drop in “between-country” inequality, fueled by rapid rises in average wealth in emerging markets. The trend became mixed after the financial crisis of 2008, when financial assets grew speedily in response to quantitative easing and artificially low interest rates. These factors raised the share of the top 1% of wealth holders, but inequality continued to decline for those below the upper tail. Today, the bottom 90% accounts for 19% of global wealth, compared to 11% in the year 2000. In other words, there was a concentration of wealth towards the top 1% (and even more to 0.1%), but with some dispersion among the remaining 99%.

The researchers conclude that the small decline in wealth inequality in the world as a whole

In short, what the report shows is billions of people have no wealth at all after debts and that the distribution of global personal wealth can be described as a few Gulliver giants looking down on the mass of Lilliputians.