Only a mass socialist, feminist, internationalist, pro-peasant, anti-racist, indigenous, and anti-colonial movement can save humanity

Only a mass socialist, feminist, internationalist, pro-peasant, anti-racist, indigenous, and anti-colonial movement can save humanity

This declaration was drafted by Daniel Tanuro and adopted by the national leadership of Belgium’s Gauche Anticapitaliste. Translated for Climate & Capitalism by Richard Fidler, who blogs at Life on the Left, with light editing by Ian Angus.

The mobilization against climate change continues to build, gaining new social layers beyond the initial circles of environmental activists and tending toward a systemic critique of capitalist productivism with its underlying competition for profit. Particularly significant is the fact that young people are joining the struggle. On March 15 more than a million people, a majority of them youth, went on strike for the climate around the world in response to the call by the Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg. The movement is very deep, although at present it is limited to the major countries of the Global North. It reshuffles cards, upsets agendas and puts all the actors — politicians, trade unions, associations, social movements — on notice to answer two fundamental questions:

- Why are you not doing everything possible to limit to the maximum the terrible catastrophe that is growing day by day, and to do so in compliance with democracy and social justice?

- How dare you leave such a mess to your children and grandchildren?

The sacred cow of capitalist growth

These two questions go unanswered because they touch on the sacred cow of capitalism: growth. “Capitalism without growth is a contradiction in terms,” said the economist Joseph Schumpeter. Today, this contradiction unfolds before our eyes as the fundamental cause of an insurmountable antagonism between capitalism and a respectful relationship of humanity with the rest of nature based on “caring” and not on looting.

If we insist on this point, it is not primarily for ideological reasons or because “degrowth” would in itself constitute a societal project, but because our capacity to limit catastrophic climate change now depends directly on the speed and determination with which society will decrease its consumption and material waste. It is urgently necessary to reduce these flows (especially CO2 flows), to escape productivism and to enter into a new mode of production of social existence underpinned by the values of sharing, cooperation, respect and equal rights. This is possible only by ending the production of exchange values for the profit of competitive capitalists through a new social engine: the production of use values to satisfy real human needs, unalienated by commodity fetishism and democratically determined in respect for the limits of ecosystems.

The radical nature of the transformation to be carried out is clear in the Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Global Warming of 1.5°C. In its summary, the IPCC concludes that global net CO2 emissions must be reduced by around 45% by 2030 in relation to 2010, and to this effect pleads for “profound transformations at all levels of society.”

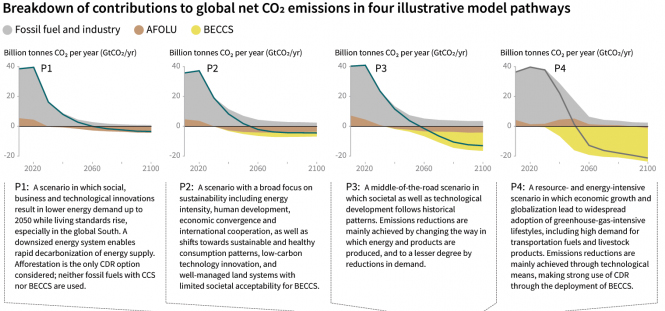

Widely reported by the worldwide media, this conclusion nevertheless presents a somewhat toned-down portrait of the situation, which is extremely serious. The full report compares four possible “pathways” or scenarios for the reduction of emissions, graphically displayed as follows:

AFOLU: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use. BECCS: Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage. CDR: Carbon Dioxide Removal

According to Scenario P1, to have one chance in two (which is not much) to remain below 1.5°C warming during this century, we should adhere to a three-stage trajectory:

- “net global emissions” of CO2 must decrease by 58% between 2020 and 2030;

- They must then continue to decrease, reaching zero by 2050; and

- Between 2050 and 2100 emissions must remain negative.

Scenarios 2, 3 and 4 show that the further we move away from this trajectory, the greater the risk of exceeding 1.5°C, which could only be corrected by withdrawing CO2 from the atmosphere using “negative emissions technologies” (NETs). The objective of a 45% reduction by 2030 suggested by the IPCC, and repeated by the media, corresponds therefore to a trajectory situated somewhere between scenarios 2 and 3, implying a slight increase beyond 1.5°C by 2050 and a fairly extensive deployment of NETs. Already in its previous report (AR5, 2014) the IPCC presented some scenarios based 95% on the use of NETs. It now confirms this approach. But this is questionable. Indeed, the degree of deployment of NETs indicates the extent of our inability to stop the runaway train of capitalist accumulation. Assuming that these technologies would help to avoid the cataclysm that is threatened by exceeding 2°C (an assumption that is probably science fiction), the fundamental antagonism described earlier would inevitably recur later in an even more acute form. That is why we are not in a “crisis” but facing a choice of civilization.

Let’s go back to the four scenarios. To understand them, one must know that “negative net emissions” mean that the Earth is absorbing more CO2 than it emits. The “net emissions” are obtained by deducting absorption from emissions. The absorption is at first natural: green plants feed on the CO2 in the air, and the CO2 dissolves naturally in water. At present, about one half of the 40 gigatonnes of annual “anthropogenic” CO2 emissions (due to human activity) are thereby withdrawn from the atmosphere. “Net global emissions” therefore run around 20GT/year. (On the one hand, we are only talking here of CO2, not the other greenhouse gases; their emissions are not accounted for in the “carbon budget.” On the other hand, CO2 absorption by ecosystems tends to decrease as a result of warming, especially because hot water dissolves less CO2 than cold water.)

To reduce emissions to zero by 2050, scenario 1 of the IPCC relies solely on the possible intensification of these natural mechanisms mainly through reforestation and improved soil management. The precautionary principle would call for remaining there, banishing NETs. But in that case it would be necessary to very, very radically confront the drive for profit. The IPCC excludes that possibility. It clearly states in its fifth report that the climate models presuppose a fully-functioning market economy and competitive market mechanisms. So full speed ahead toward technology. But what does that have in store for us?

The key political question

The most mature of the “negative emissions technologies” is bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). It consists of replacing fossil fuels with biomass and storing the CO2 from combustion in deep geological layers. As green plants grow by absorbing CO2, the BECCS in the long run should lower the atmospheric concentration of this gas. Besides the fact that there is no certainty that geological reservoirs are impermeable, this “solution,” if it is to have a significant impact, requires that very large areas (equivalent to about 15%-20% of today’s permanently cultivated land area) be devoted to the industrial production of bioenergy. Whether these lands are in cultivated or non-cultivated areas, this can only intensify dangerously the already considerable pressure that bioenergy exerts on biodiversity and food crops today. Therefore every effort should be made to avoid BECCS. Should it nevertheless be implemented in order to avoid the worst, it would have to be very strictly limited. In any case, it is categorically necessary to promote the strongest and fastest possible reduction in emissions.

But that is precisely the political crux of the question. Capitalism has been built and continues to be built on fossil fuels. Governments have done almost nothing since the Earth Summit (Rio, 1992), and emissions have continued to increase so we are now in a critical situation. The largest and fastest possible reduction of emissions would necessarily involve the very rapid destruction of a huge amount of capital, of an unprecedented “bubble.” The most important sectors of capitalism oppose this with all their might, so two tendencies are crystallizing in the ruling class: that of Trump, Bolsonaro and some other climate denying leaders on the one hand, and on the other hand that of “green capitalism” which, to avoid an excessively brutal bursting of a bubble that is too big, argues in effect for scenario 4, with a massive deployment of BECCS, a “temporary overrun” of the 1.5C limit and cooling of the planet during the second half of the century — since these people imagine that the Earth’s temperature is as easy to regulate as that of their “smart house.”

Everyone understands that the first tendency is simply criminal, but the second one is barely less. For three reasons:

- No one knows if BECCS and the other technologies envisaged will actually remove enough carbon from the atmosphere to return below 1.5°C after exceeding this threshold;

- No one knows how to avoid the likely adverse effects of BECCS and other so-called solutions, especially on the biodiversity and food of the world’s population; and

- Climate change is a non-linear phenomenon. The risk increases very seriously that a major accident with irreversible consequences may occur during the “temporary overrun,” for example the breaking up of the gigantic Thwaites or Totten ice-sheets in the Antarctic, which would ultimately bring about an increase of three to six metres in the ocean level.

Gauging the scope of a staggering challenge

We repeat: irrespective of what the IPCC says, every effort must be made to try to fit within scenario 1 and to follow the three stages in the trajectory cited above, or to deviate from it as little as possible. This should be the goal of the climate movement. But we must be aware of what that means. It means considering the following elements:

- CO2 emissions account for 76% of “anthropogenic” greenhouse gas emissions;

- 80% of CO2 emissions are due to the burning of fossil fuels;

- More than 80% of humanity’s energy needs are covered by the use of these fuels;

- The fossil energy system is largely unsuited to renewable sources, and must therefore be scrapped as soon as possible, whether the facilities are profitable or not;

- These facilities account for about one fifth of the world’s GDP, to which must be added the assets constituted by fossil fuel reserves, nine-tenths of which must remain in the soil if we are to have a little more than one chance in two not to exceed a 1.5°C temperature increase.

- The most recent fossil installations are located in the so-called “emerging” countries (China, India, Brazil, in particular) and in other countries in the global South, which are not the main historical contributors to the climate imbalance;

- The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (adopted in Rio in 1992) states — rightly! — that each country must contribute to saving the climate according to its historical responsibility and capabilities;

- Renewable energies are enough to satisfy human needs, but the technologies needed for their conversion are more resource-intensive than fossil technologies: it takes at least ten times more metal to make a machine capable of producing a renewable kWh than to manufacture a machine able to produce a fossil kWh. The extraction of metals is a big consumer of energy (and water).

From these data, the conclusion to be drawn is obvious: Scenario 1 — optimum for humans and non-humans — represents a gigantic challenge, not only technically and conceptually, but also and above all in terms of the necessary coordination for global balances. Indeed, it is a matter of respecting the key principle of North-South climate justice (designated as the “principle of common but differentiated responsibilities” by the UN Framework Convention) while:

- making huge investments to build a new global energy system based 100% on renewables;

- using for this construction an energy that is still more than 80% fossil, therefore emitting CO2;

- using part of this energy to extract and refine the rare metals and rare earths that are essential for the operation of “green” technologies (the extraction of these metals consumes a lot of energy and water, and generates a lot of waste because of their diffuse presence in the rocks);

- and staying within the envelope of the drastic reductions in global net CO2 emissions mentioned above (58% reduction between 2020 and 2030, etc.).

We say it forcefully: it is absolutely impossible to comply with the bundle of socio-political, temporal and physical constraints summarized above without an overall and extremely radical anti-capitalist program. It’s not just about planning and streamlining production; production needs to be drastically reduced in order to reduce the amount of energy consumed, wherever possible.

Without this drastic reduction, it will be impossible to offset the emissions from the construction of the new renewable energy system, on the one hand, and to prioritize the right of the South — especially the countries that international institutions scornfully call “the least advanced” — to develop, using what fossils humanity can still use, on the other hand.

Without compensating for these two causes of emissions, there is no way to reduce net global emissions by 58% by 2030, by 100% by 2050 and by more than 100% in the second half of the century. Even under the assumption — promoted by the IPCC — of a 45% reduction in emissions by 2030, the problem is insoluble if we do not go beyond the capitalist logic.

Make what is necessary possible

The growth dynamic of capital and the inaction of its political representatives have literally brought us to the brink. What should be done to avoid tipping over it? That is the question to ask. First, it is imperative to answer this objectively, without subjectively limiting ourselves, that is, without being confused by what is or is not feasible within the capitalist political, economic, social and ideological context, which distorts everything and stands reality on its head. Secondly we must see what is to be done to make possible what is necessary, what obstacles must be overcome, how much time may be needed, with what consequences, and how to confront them. To proceed in the converse direction, starting from the “capitalist possible” in order to determine what “must” be done (in reality, what capital allows) is to posit that the historical and social laws of profit must prevail over the physical laws of the Earth’s climate. This is absolute methodological nonsense (and by the way, this nonsense shows that the ideology of human “domination” over the rest of nature is not only absurd but also blinding, and therefore dangerous!).

Objectively, it is indisputable that blocking the growing disaster requires a very radical anticapitalist plan, completely reorienting production, exchanges, relations with the “global South” and the worldview. In the so-called “developed” capitalist countries, the main axes of this plan would be:

- Suppress unnecessary and dangerous production. “Every tonne of CO2 that is not emitted counts,” the scientists tell us. They do not draw the logical conclusion: the priority should be to stop the production and consumption of weapons, packaging and plastic gadgets, to combat the obsolescence of products and to ban advertising. In the USA, as an indication, the combined emissions of the military industry and the Defense Department are around 150 million tons of CO2 per year (not counting the emissions of the 700 or so US military bases abroad!).

- Suppress the useless transport of commodities, localize production as much as possible, favor short supply circuits, impose an increasing tax on kerosene (to be distributed to the countries of the South via the Green Climate Fund). Air and sea transport emissions currently account for 5% of global CO2 emissions and are increasing rapidly as a result of capitalist globalization. According to a study by the European Parliament, these sectors could produce respectively up to 22% and 17% of global CO2 emissions in 2050. It is urgent to close this tap.

- For the mobility of people, invest massively in public transit and effectively promote the use of bicycles in good conditions. Discourage the use of the private car, promote employment close to home, provide more services within local territories. Rationalize air travel by means of free, personalized, non-exchangeable air mobility rights.

- Create territorial public firms assigned to insulate and renovate all buildings within 10 years. The neoliberal policy of incentives and taxes on insulation-renovation is too slow, socially unfair and focused more on promoting the production of renewable energy by home owners — and on the irrational development of the markets of “green capitalism” — rather than reducing energy consumption through insulation. Urgency and reason require us to end this policy as soon as possible.

- Leave fossil fuels in the ground. Expropriate and socialize the energy and finance sectors without compensation or repurchase. Set up a decentralized public energy service. The fossil and financial sectors are intimately linked through investment loans and share ownership. Without breaking the lock they constitute, it is not possible to organize in ten years the rapid transition to an economy based on 100% renewables (and thus nuclear-free). This is the keystone of the structural reforms to be imposed.

- Break with agribusiness and capitalist exploitation of forests. Increasing natural absorptions of CO2 does not replace the reduction of emissions but complements it. Promote agroecology using appropriate techniques to accumulate maximum carbon in soils. Promote direct links between consumers and producers. Ban industrial farming and popularize a non-meat diet. Replant hedges, restore wetlands, stop “concretization.” This is the spare wheel, to implement immediately.

- Respect North-South climate justice. This implies in particular: abolish debts; at the least honor the commitment of Northern countries to give $100 billion a year to the Green Climate Fund; cover in addition the “losses and damages” caused to the South by the warming provoked mainly by the North; abolish the patent system on energy technologies; ban the market in carbon emissions credits, carbon offsets, biofuel imports and other types of relations characteristic of “climate neo-colonialism”; guarantee freedom of movement and settlement for migrant people.

A better life for the greatest number

Short of resorting to despotic methods, it is obvious that such a plan is not even conceivable if it does not also include an equally radical social component. This is essential in particular if we are to properly address the issue of changes in social behavior. By themselves, focused on consumption, some of these changes are likely to be “unpopular” among certain segments of the population (for example, kerosene taxation and air travel rationing). Observing this through the small end of the telescope, some ecologists (from well-to-do circles) call for a “strong government.” However, ending the capitalist dictatorship of profit in the sphere of production makes it possible to trace in the sphere of consumption the path of an ecological transition which is synonymous not with regression but with a substantial strengthening of democracy and improvement in the quality of life of the social majority. This is the job facing us if we are to make the transition desirable.

In the countries of the North, the main axes of this second component of the anti-capitalist alternative are the following:

- Redistribute wealth, and restore equal liability of all incomes — including from global sources — to progressive taxation. Determine a maximum salary. Refinance the public sector, education, research, and the health, childcare and cultural sectors. End the subordination of scientific research to profit, refinance it, orient it towards supporting the transition and improve the status of researchers;

- End capitalist market supremacy: free education, public transit, health care, child care. No charges for consumption of water and electricity corresponding to basic needs, with steeply rising prices beyond that level;

- Ban layoffs and ensure decent jobs and incomes for all. Provide training in new trades for workers in the activities to be suppressed, while guaranteeing maintenance of income, social conquests and work collectives under their control. Enact a sliding scale of hours of work for all without loss of salary to ensure a radical reduction in the work week, with costs paid by the entire capitalist class. Lower the retirement age to 60 for everyone. Extend maternity and paternity leaves. Job guarantees and the shorter work week without loss of pay are necessary not only to confront the challenges of climate change and the digital revolution, but also to ensure that the needed economic and social measures do not adversely alter social relations to the detriment of the work force. Greater leisure is also likely to open opportunities for other pleasurable pursuits that can supplant the consumerist pressures that serve as a substitute for the misery of human relations dominated by commodity fetishism.

- Radical extension of democratic rights. Voting and eligibility rights at all levels, for everyone from the age of 16. Elected officials to be subject to recall, their incomes aligned with the average wage. Active policy aimed at extending citizen control and participation, particularly in the various aspects of the transition plan (such as insulation-renovation of buildings, transport and mobility, economic reconversion, changes in the agricultural model, management of territories, etc.). Maximum decentralization and democratization at the territorial level.

- Equal rights for women and LGBTQIA+. End discrimination in education, employment, in the city. Gender parity in representative assemblies and all organs of the ecological transition. Free abortion and contraception on demand. Socialization of the tasks of social reproduction.

- Develop a culture of caring, responsibility and sobriety. Increased support for adult education. Ecological reform of education, aimed at awakening consciousness of belonging to “nature.” Strengthening and socializing care activities for people and ecosystems. Municipal and public management of resources (water, renewables, scenic sites, etc.) under democratic control. Development of a dense network of repair / recycling / reuse / reduction activities supported by the public authorities. Encouragement to civic activities and respect for the autonomy of social movements.

Small steps and a large gap

As Einstein said: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” By regarding as sacred “the fully functioning market economy and competitive market behavior,” the IPCC itself closes off any possibility of resolving the climate problem. It is indispensable to reject capitalist “realism” — this insane profit drive — if we are to find a way to limit the catastrophe and prevent it from becoming cataclysmic.

The main difficulty is not technical but social, and therefore political: the necessary alternative cannot be organized from above. It requires imperatively a powerful mobilization at the base, a generalized responsibility. Let’s dare to say it: we need a global self-management revolution to democratically address, at all levels, the combined social and environmental crises. Only the exploited, the oppressed and the youth can go all the way in bringing about the indispensable reforms, in all areas. However, there is a chasm today between this urgent anticapitalist alternative and the level of consciousness of the majority of society. How is it to be overcome, to be bridged, at the earliest possibility? That is THE strategic problem to be resolved.

As anticapitalists, we are confronted daily with this objection: “You are right, of course, but what you propose lacks credibility, it is not realizable, we need concrete answers, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” So the question arises: shouldn’t we opt for small steps? Or conversely, admit that “we’re fucked,” that “collapse” is inevitable and that the only way out is to “create small resilient communities,” as the “collapsologists” say?

Anticapitalists are in favor of reforms, we do not postpone everything to the “big day” of the revolution. Small steps are positive when they strengthen the social movement and encourage it to go forward. What we question is the idea that it is possible to introduce another society gradually through a strategy of small steps. Why? Among other things, because this strategy spreads the transition over time, in flagrant contradiction with its urgency. We also question the “miracle solutions” that often accompany it, and that fail to meet the challenge. So what is to be done, what perspective is to be adopted, what strategy can we propose that will not be paralyzed between insignificant minimalism and impotent maximalism?

First, tell the truth…

We think we must first tell the truth. Our anticapitalist alternative leaves you wanting more? That is normal, it could not be otherwise. Together, we need to transform your hunger into an appetite for something else, to generate the idea of a society that produces less and shares more, for real needs, in respect for humans and non-humans, a society that appeals to the imagination. That is the function of the 13-point draft program outlined above. It is necessary to fight both the anxiety-inducing defeatist discourse and the pseudo-realistic discourse propagating the illusion that the optimum scenario (the IPCC’s Scenario 1) could be realized — or at least approached — by following a less radical path.

In the United States, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposes a “Green New Deal.” In Europe, Jean Jouzel and Pierre Larrouturou plead for a “climate finance plan.” There are now more and more such proposals for less radical paths. The lines are moving, and that is undeniably a positive effect of the social movement. However, if we examine them in detail, we find that these proposals have three points in common:

- they bypass the key question of the indispensable reduction in energy consumption, material production and transport;

- they do not exclude the use of negative emission technologies such as BECCS, or so-called “miracle technologies” such as hydrogen;

- most often, they refrain from taking a clear stand for compliance with the commitments toward the South, against the purchase of emission credits and carbon offsets, etc.

Therefore, we must be clear: these less radical paths, which are presented as more realistic than the anti-capitalist alternative, fit more or less clearly (very clearly for Larrouturou-Jouzel, who want to save the European Union) within the project of “green capitalism.” They all involve varying degrees of “climate neocolonialism” and harsher warming effects on humans and non-humans than in Scenario 1 — not to mention the sword of Damocles of the irreversible and large-scale tipping point mentioned above.

… and build social mobilization

The strategic problem of the gulf between objective necessity and subjective possibilities will not be overcome by proposing alternatives at a discount. It can only be overcome through the development of social mobilization. This development is indeed the lever to advance the level of consciousness on a mass scale. The line that we propose in order to do this can be summed up in a few words. Do not let up. Instead, expand, converge, organize, democratize, deepen, challenge, radicalize, invent. Let’s briefly comment on them:

Never let up! The task before us is long-term. We have a chance to limit the damage only if we place it within the perspective of a permanent struggle. In the immediate term, this means in the first place rejecting any idea of an electoral truce, in the framework of the European election or other polls. In the longer term, this means consciously building on the destabilization and delegitimation of the established powers. The political agenda, its temporality and its institutions are not ours. “We do not defend nature, we are the nature that defends itself.” Let us look to each perceptible manifestation of the disaster that is under way — there is no lack of them, alas! — as a way to increase the pressure and relaunch action.

Expand! The movement has been constantly expanding since the heat wave of the summer of 2018 in the Northern Hemisphere. This is one of our main assets. We must consciously continue on this path, organize new mobilizations, repeat the strike of March 15 on a larger scale, methodically lay the groundwork for a global uprising for the climate involving tens of millions, hundreds of millions of people. We are life in the face of death. Our ambition must be commensurate with the challenge.

Converge! It’s not just about winning new sectors of youth, or new regions, new countries. It is also a question of working patiently to bring together social-trade union, feminist, peasant, anti-racist, anticolonial and indigenous struggles at the grassroots level, across borders. The contribution of feminists is important, especially because they emphasize the importance of “caring.” That of indigenous peoples is inspiring because it shows the possibility of a new vision of relationships between humans and non-humans. The peasants of Via Campesina are already at the forefront, with their agroecological program and direct action practices. The key strategic challenge is to detach the social-trade union movement from its alliance with productivism; this means, primarily, the reappropriation of the collective reduction of labor time, making it THE ecosocialist demand par excellence.

Organize, democratize and deepen! These three goals go hand in hand. In general, with some exceptions, the current movement suffers from a lack of organization and democracy. This is partly the result of its spontaneity, obviously a good thing in itself. But there is a void. Today, it is filled by individuals, by long-standing associative structures, and by initiatives of small groups on social networks. We must go beyond this stage, avoid “substitutism” and prevent attempts to coopt the movements. Not to let up, but to build long-term convergences requires a movement rooted in non-exclusionary and democratic grassroots structures, that is to say, general assemblies that elect people with revocable mandates to represent them transparently wherever the struggle is coordinated and determines its objectives. This mode of organization is the best way to deepen awareness, to move from immediate issues (sorting waste, etc.) to more structural issues.

Challenge! Greta Thunberg has shown the way. Political and economic leaders are trying to co-opt her image, but so far she has not fallen for “greenwashing.” In Davos, in front of the European Parliament and elsewhere, she has blamed the leaders without compromise, without hesitation. Let’s follow her example. Let’s abandon any illusion that the political system “will come to understand” the need to be “more ambitious” because there are so-called “win-win” solutions to reconcile growth and profit with the climate (that’s a joke, there are none!). Let us adopt an autonomous position, of systematic and uncompromising distrust. Let’s dare to disobey. Systematically, joyfully and deliberately let us undermine the legitimacy of the wealthy, their political representatives, and of all those who refuse to leave behind the productivist and growth-oriented framework.

Invent! As part of the challenge, legal actions such as 350.org’s trial of the century and immediate demands have their place. Let’s challenge decision-makers to take concrete action straight away: include the obligation in law to reduce emissions, insulate all public and parapublic buildings, make public transport free, ban advertising, abandon major works, etc. The list of possibilities is endless. In the longer term, the climate movement means that we have entered a new period of history in which the “ecological question” will traverse and articulate more and more clearly all social issues. Working towards the convergence of struggles in an intersectional perspective follows logically. This poses now a long series of unresolved questions. For example: what political tool can be forged in the course of the struggle so that it is able to proceed from the anti-capitalist struggle to the construction of a new world?

Radicalize! We must become aware of our strength. Without the climate movement, COP21 would not have set the goal of keeping warming below 1.5°C. We must demand that this step forward be followed by concrete measures, and ensure that they are up to the challenge and socially just. This is the meaning of the current movement. The wealthy and their political representatives are under pressure because they know that the challenge of climate change is potentially revolutionary. All currents are under pressure, so the lines tend to move. So, rather than letting ourselves be drawn into the mined terrain of the strategy of small steps, let us widen the gap. To do this, confront each new proposal with the scientific diagnosis of what should be done to stay under 1.5°C of warming without resorting to dangerous technologies while respecting obligations towards the South as well as social justice. Finding that “there is no fit” will help the movement to become radicalized to the point where it will be able to propose itself an anti-capitalist program that meets the challenge, and to fight to impose the formation of a government on this basis.

A race at frightening speed

Will it work? Nobody can guarantee it; we are caught in a race at frightening speed between the hope of salvation and a plunge into barbarism. From this angle, the situation presents some analogies with the one that existed before the First World War, which Lenin characterized as an “objectively revolutionary situation.” The subjective factor was totally unable to prevent the butchery of 1914-18, but from that butchery there arose the Russian revolution — which was suffocated from outside and strangled from within. A century later, a similar question is posed, on an even more disturbing scale: how far will humanity have to sink into the trenches of climate catastrophe before finally turning against capitalism to rid itself of this criminal system once and for all? Will the revolution — the irruption of the masses on the scene where their fate is at issue — meet the challenge? Will capitalism, on the contrary, maintain its bewitching power?

These questions are unanswered. They remind us of Gramsci, and his famous quote about combining the pessimism of the mind with the optimism of the will. That optimism is a categorical imperative, because we are certain of only one thing: the outcome of the race between the disaster and consciousness of the disaster depends on the re-emergence on a mass scale of an emancipatory project capable of overcoming the terrible threats to humanity posed by productivist folly.

For the ecosocialist project, there is no shortcut, no way other than struggle, .