The author of Fossil Capital and The Progress of This Storm says there are reasons to be hopeful, but success depends on building a global movement of unprecedented scale

This interview was published in the Swedish journal ETC on February 5, and translated for Verso Books by Sam Carlshamre.

by Rasmus Landström

Andreas Malm sits in his office in his apartment in Malmö. He is looking uncomfortable. The question I asked — if he is active in any political organisation — seems to have opened the floodgates of his bad conscience. Well, of course, he is a member of Socialistiska Partiet (The Socialist Party — a Swedish left-wing organisation with its roots in the Trotskyist tradition) and Klimataktion (Climate Action), but the days when he went blocking airport runways seems to be over. Last year he missed the major actions against the coal plants in Germany due to a foot injury.

“Since I became a researcher I have turned into a kind of ‘Armchair Activist,’ and it’s something that I makes me feel incredibly embarrassed.”

He scratches his head.

“But I do try to participate in as many demonstrations and manifestations as I can; and why not a riot every now and then? I guess you shouldn’t write that last bit though.”

An internationally renowned researcher and authority in the field of Human ecology who participates in riots? For those of us who have followed Andreas Malm’s trajectory over the last decades that doesn’t come as much of a surprise. For many years he was a well-known character of the non-parliamentarian, far-left Sweden. He started out with Palestine activism in the 1990s, which led to the book Bulldozers Against a People — in which he chronicled his own work with activists in some of the most dangerous parts of Palestine’s. Later he wrote two books on the workers’ struggle in Iran together with his partner Shora Esmailian — which led to them both being banned from returning to the country. He has also been an activist in the struggle against Islamophobia and American imperialism, and has written books on these topics as well.

“Since I became a researcher I’ve been drawn into this academic bubble. I could say that that’s because I have a small child to take care of, but it still gives me a very bad conscience.”

Malm sighs and looks quite unhappy. I figure its time to change the subject. After all, the reason I’m doing this interview isn’t his personal track record as an activist, but his contributions as a researcher and political commentator. I start by asking how he got engaged in the struggle against climate change.

“In the early 2000s I considered the whole issue of climate change a bit “petty bourgeois,” as did most of us on the radical, non-parliamentarian left. Why should we care about polar bears or melting ice caps when there were more important issues, such as the workers’ struggle, right here? But then I came across Mark Lynas’ book High Tide; I read it and it got me thinking.

“At that time, I was active in issues concerning the Middle East, and suddenly it struck me that a democratic Iran would never come about if there was no potable water around. That made me write the book Det är vår bestämda uppfattning att om ingenting görs nu kommer det att vara för sent (It is our firm view that if nothing is done now it will be too late). Since then I have kept working on these issues within the academy.”

Inspiring Naomi Klein

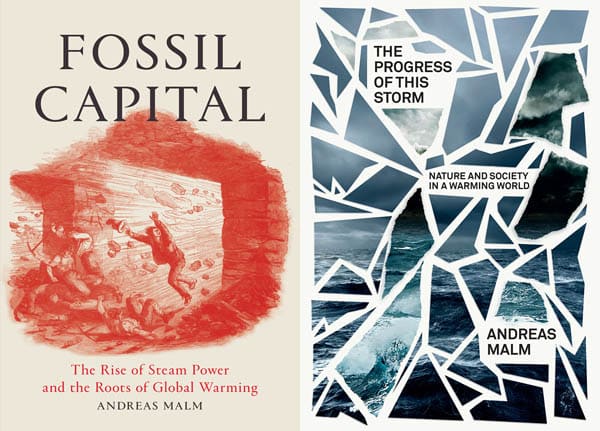

Malm presented his dissertation Fossil Capital in 2014, at Swedens’ Lund University. The book is a tome of 797 pages in total, and a breakthrough in the debate on climate change. I read it myself when it was newly published, and it gave me an epiphany. In it Malm claims that, even by the mid 19th century it was far from given that the global economy would come to be dominated by fossil fuel. Based on a massive amount of empirical data, Malm showed that the eventual breakthrough of coal power was not due to its efficacy as a power source, but because it made controlling the workforce much easier. While hydro power — which at the time was both cheaper and more energy-efficient — was tied to certain locations of rivers in open landscapes, steam engines could be set up in towns and cities, where there an infrastructure of schools, poor houses and police forces was already in place. This in the long run made it easier for capitalists to exploit the work force and guarantee their profits.

The conclusions of the dissertation were revolutionizing: capitalism and the fossil economy are much more intertwined than we had hitherto imagined. Thus Malm’s worked opened for research within the field now known as Capitalocene — his research inspired Naomi Klein in her writing This Changes Everything.

Today Malm is a kind of “red star” within the debate on climate change. His forthcoming book The Progress of This Storm (Verso, 2018) — in which he makes the case for a Marxist perspective on the climate — has already provoked debate within the field.

I ask Malm what has changed since he wrote the dissertation.

“I sense a growing interest in issues of energy and climate change amongst Marxists, and a growing interest in Marxism amongst those studying energy and climate change. Just yesterday I read an article in one of the leading climate change journals — The Anthropocene Review — in which the editor concluded that much of the research in the field is now guided by Marxist analyses of climate policy and ecological issues. He found it lamentable, but for me its refreshing, of course.”

But, I ask, is a Marxist perspective on these issues really what is called for today? Aren’t there signs that the global economy is already shifting? Since the dissertation, we have gone through what is known as the energy revolution, i.e. the shift into a situation where solar, wind and hydro power are commercially viable, and have started to compete seriously with fossil fuels. For example, already in 2015, the worlds wind power reached a higher combined productivity than the sum total of all that of all the world’s nuclear plants.

Malm sighs once more.

“This has become a very prevalent idea. But what those who are enthusiastic about market solutions disregard is the fact that the fossil power infrastructure keeps expanding at the same time. With Trump in the White House the oil companies have more political power in the United States, and new pipelines and highways are being prospected as we speak. In India many new coal power plants are being built, and in China the winding down of coal power has been reversed. For the world’s climate it doesn’t matter much if the market for renewable fuels is booming. What matters is that we stop using fossil fuels, right now.”

A growing movement against climate change

Not since the 1950s have as many pipeline projects been under construction as today, Malm underscores. At the same time there are reasons to be hopeful. The movement against climate change is growing. In Germany large protests against coal power plants are held every year. In the US activists are blockading the building of new pipelines. Malm gets enthusiastic as he talks about how Bill de Blasio, the mayor of New York City, recently announced that the city is planning to sue five giant oil companies for contributing to the hurricanes that have recently hit the city.

“At the press conference he sat flanked by Bill McKibben and Naomi Klein. The message couldn’t have been any clearer: this only came about as a result from the pressure mounted by the climate movement. We have to appreciate the symbolic power of something like that.”

Then he turns pessimistic again.

“But the movement still needs to grow so much bigger, and the different groups all over the world have to be linked up on a scale we have not seen so far. Otherwise we don’t stand a chance against fossil capital.”

Excellent slicing comment from Richard Smith, the author of the excellent The God that Failed take-down of green capitalism. Yet for Smith to posit “rethink strategy” as the needed step seems to fall into the same hopeism trap that afflicts green thinkers with children – the problem is not one of determined fate, but of “strategy”?

I did buy Malm’s newest book to see what he makes of other greenish thinkers, but to see approval of the faith duo of Klein/McKibben as representing a “symbolic victory” is to enter into the realm of liberal fantasy, one that social nihilism eats as a snack.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jan/11/new-york-city-oil-industry-war-divestment

https://theintercept.com/2018/01/11/new-york-city-big-oil-fossil-fuels-climate-change/

When I see Bill McKibben, Naomi Klein, and Bill DeBlasio congratulating themselves on their latest fossil fuel divestment victory, what I think of is this:

https://nypost.com/2017/06/02/de-blasio-claims-hes-a-champion-of-the-environment/

and this:

http://www.businessinsider.com/us-gas-consumption-new-high-2016-11

and this:

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/06/06/us-oil-output-to-hit-record-10-million-barrels-a-day-next-year-eia.html

What are they celebrating? And what kind of example is Bill DeBlasio? There he was lecturing to his fellow New Yorkers about how THEY need to change but while he’s chauffeured from Gracie Mansion to his Brooklyn gym every morning in a 6,000 pound gas-hog Suburban instead of taking the subway. And not just one SUV, 3 of them go in convoy then the drivers sit outside with their engines running for heat or AC while he’s in the gym.

Five years after the fossil fuel divestment campaign took off, actual fossil fuel consumption has not been reduced by one drop in the United States or the world. It has increased every single year. Fossil fuel divestment is just green capitalism, a sham. It does not attack fossil fuel consumption at all, just portfolio investment. When what we’re doing is failing, isn’t it time to rethink this strategy?