What if?

Many movies and novels start with that question. Often the contingent event is small — the movie Sliding Doors hinges on whether or not the main character boards a subway car. A Wonderful Life considers what the town would have been like with a different banker. Sometimes novelists and historians try to consider world-historic what ifs: What if the South had won the Civil War, or Germany had won the Second World War?

Some Marxists think that the course of history is determined by great and powerful forces, so small changes wouldn’t make big differences in the long run. But, as Stephen Jay Gould often said about evolution, if the tape of history were replayed, it would probably turn out differently. Trotsky wrote that if Lenin had not been present, the Russian Revolution would not have occurred in 1917 — that statement led to much debate about the role of the individual in history, but I find it entirely reasonable.

Lately, I’ve been researching issues related to disease in nineteenth century London, and a visit to one of the most famous and notorious centers of infection brought some what ifs to mind. In particular, if one small thing had been different, the course of working class and socialist history might have been very different indeed.

The location is now the intersection of Broadwick and Lexington streets, in the expensive and fashionable Soho district. In 1854, it was a poor working class district, and the streets were named Broad and Cambridge. In front of the small house at 40 Broad Street, there was a pump where families who lived in the area got water for drinking, cooking and cleaning. Its water was unusually good tasting, so people from blocks away used it in preference to closer wells.

Two million people lived and defecated in mid-Victorian London, most of them in houses and tenements with no running water and no drains. Sewers scarcely existed in working class neighborhoods. Excrement accumulated in cesspools and privies and overflowed into the streets. It smelled, and it killed: cholera, a disease we now know is mainly spread in feces-contaminated water, swept London — indeed, all of Britain — in deadly epidemics, in 1832, 1848, 1854, and 1866. Tens of thousands of people, mostly poor, died in agony, dehydrated by uncontrollable diarrhea and vomiting.

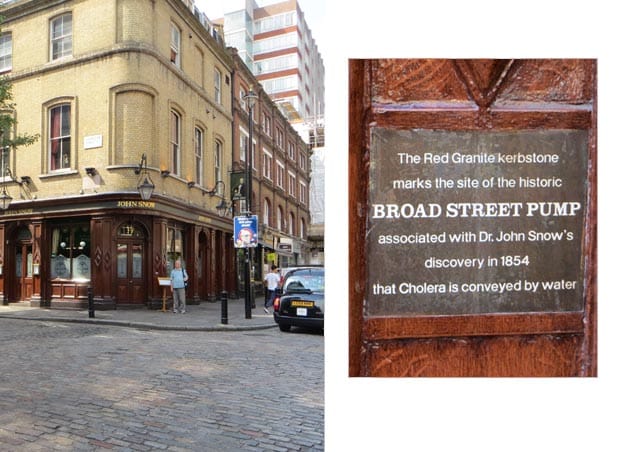

During the 1854 cholera epidemic, most deaths occurred south of the Thames, but an isolated outbreak killed over 700 people in Soho, less than two kilometers north of the Parliament Buildings. Dr. John Snow, a society doctor with a social conscience, traced the outbreak to the well at 40 Broad Street: most people who got water there contracted cholera, while neighbours who got their water elsewhere escaped. Snow convinced the local authorities to remove the pump handle, and the epidemic abated.

By the front door of 40 Broad Street, just a few feet from the pump, was an opening above an underground cesspool where wastewater and excrement were routinely dumped. So, when five month old Frances Lewis had a bad case of diarrhea in August 1854, her mother rinsed the baby’s diapers in a bucket, and emptied the bucket into the cesspool. The diarrhea proved to be cholera — Frances died, and her infected feces leaked through the cesspool’s decaying brickwork into the well.

The what if? possibilities are many. What if the landlord had maintained the cesspool, or paid for it to be emptied? What if Frances Lewis had not contracted cholera? What if her mother had emptied the diaper pail elsewhere? What if Dr. Snow had chosen to stick to rich patients (he was Queen Victoria’s anesthetist during childbirth) and stayed out of Soho? What if the parish authorities, who really didn’t believe his theory that the disease was waterborne, had refused to remove the pump handle?

I was thinking about such issues when Lis and I visited the pump site this past summer. There’s not much to see: the house where Frances Lewis died is long gone, and even the street names have changed. But there is a nice pub named after John Snow at the corner, and a small plaque near where the pump used to be. Lis took these photos.

Left: Ian in front of the John Snow pub. Right: Plaque on north wall of John Snow pub.

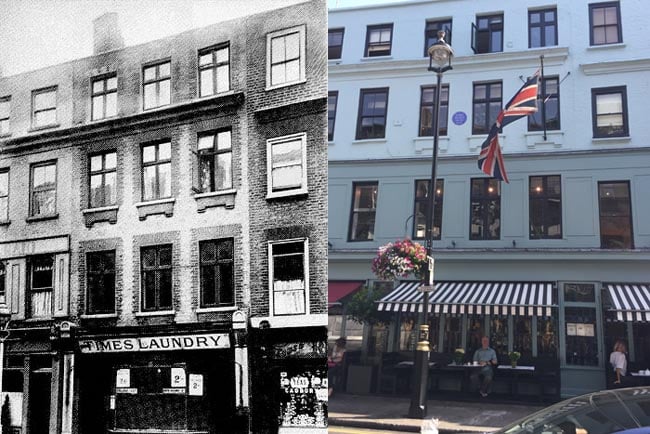

After visiting the Broad Street pump, we went to 28 Dean Street, where Karl and Jenny Marx lived with their young children and housekeeper Helene Demuth, from 1851 to 1856. Like much working class housing in London, 28 Dean was a large 18th century house that a slum landlord had acquired and rented out one room at a time. The entire Marx household occupied two rooms, probably one-time servants’ quarters, under the eaves on the third floor. There was no running water — water had to be carried up three flights — and they shared a ground floor privy with other tenants. The high child mortality rate in working class London devastated them as well: three of their children, Edgar, Guy, and Frances, died while the family lived on Dean Street.

The picture on the left below shows 28 Dean Street in the 19th century; the one on the right shows me drinking an expensive (and decidedly mediocre) cup of coffee at the restaurant that now occupies the ground floor. Below is the small blue plaque on the outside wall, below the flat where the Marx family lived.

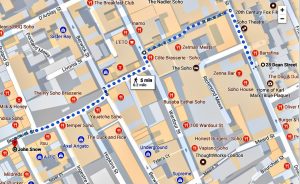

I was struck by how close 28 Dean Street was to 40 Broad Street. Just two-tenths of a mile, about 350 yards. We walked it easily in five minutes. Karl Marx and family lived on Dean Street while cholera was raging next door.

Remember that people went out of their way to get the particularly tasty water from the Broad Street pump. It’s not unreasonable to speculate that Karl or Jenny or Helene might have filled a water bucket there. Perhaps they even did so, before the cholera outbreak. If they had done that in August 1854, the Grundrisse and Capital and the Critique of the Gotha Program might never have been written. and Marxism wouldn’t exist in the form we know.

Engels would have kept the flame of historical materialism burning, but the extraordinary partnership that created scientific socialism would have been broken. The working class movement would have developed in a different way.

I don’t have any profound speculations about what might have been different, or how the movement might have evolved without Marx, but I have no doubt that one drink of water could have changed history.

What do you think?

===

Ian

PS: For the full story of John Snow and the Broad Street pump, I recommend Steven Johnson’s book, The Ghost Map. George Novack’s essay, The Importance of the Individual in History-Making, is a good place to start on that subject.