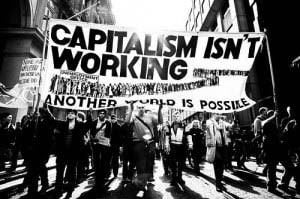

Under capitalism, everything is a business opportunity. Disasters are not viewed by business leaders as problems to be solved, they are seen as circumstances of which they must take advantage.

Under capitalism, everything is a business opportunity. Disasters are not viewed by business leaders as problems to be solved, they are seen as circumstances of which they must take advantage.

by Jake Johnson

Common Dreams, October 3, 2016

In his remarkable study When Corporations Rule the World, David Korten recounts a meeting he attended ahead of the 2012 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The meeting was led, Korten notes, by indigenous leaders who were anxious about the direction in which global environmental policy was being steered. They were also, quite justifiably, worried about who was doing the steering.

“In the conference’s preparatory meetings,” Korten writes, “corporatists … proposed that to save nature we must put a price on her.”

It’s a familiar story: Capitalism, we are often told, can be made green. Incentives can be established. The corporations previously leading the way in pollution, plunder, and exploitation can, with a few adjustments, become the world’s leaders in the development of clean energy and pave the way to a sustainable future.

As is often the case, it is those who have seen up close the harm done by corporate greed who most quickly see through the facade. “These indigenous leaders recognized that this proposal would accelerate the monopolization by the richest among us of the resources essential to human life,” Korten observed. “Their position was clear and unbending. Earth is our Sacred Mother and she is not for sale. Her care is our sacred responsibility. Her fruits must be equitably and responsibly shared by all.”

This conflict between capitalism and the environment is not, of course, uncharted terrain. Naomi Klein, in her bestselling book This Changes Everything, argues that an economic order predicated on the relentless pursuit of profit is incompatible with a world in which natural resources are used with the necessary care and restraint.

It truly is, as the subtitle of Klein’s book notes, “capitalism versus the climate.” Terrifyingly, capitalism is winning.

Under capitalism, everything is a business opportunity — catastrophes, from tsunamis to wars, are no exception. In fact, as Klein documented in her earlier book The Shock Doctrine, disasters are not viewed by business leaders as problems to be solved; rather, they are seen as circumstances of which they must take advantage.

But capitalism does not merely wait on the sidelines for these opportunities to arise. “An economic system that requires constant growth, while bucking almost all serious attempts at environmental regulation, generates a steady stream of disasters all on its own, whether military, ecological or financial,” Klein notes.

Disasters of the kind Klein describes have become commonplace during the neoliberal period, in which markets have been deregulated, public services have been privatized, governments have become unresponsive to the needs of the citizenry, and trade accords have empowered corporations to run roughshod over sovereign nations in pursuit of profit. The exploitation of the global poor in the process is a given — as Arundhati Roy observed in a piece condemning the government of India for sanctioning the displacement of indigenous communities in an effort to clear the way for corporate mining projects, it’s now just “business as usual.”

“The battle lines,” she wrote, “are clearly drawn.”

Similar such cases, in which poor people are seen as disposable and their communities as capitalism’s waste dumps, abound.

In North Texas, the “birthplace of modern hydraulic fracturing,” residents have been suffering the consequences of living near the operations of the oil and gas industry for years — consequences that include, but aren’t limited to, heart problems, breathing troubles, and birth defects. “I’ve been trying to sell my house,” one resident told the Center for Public Integrity. “I’ve got to get out of here or I’m going to die.”

In 2015, Scientific American reported an unsurprising fact, by now almost a truism: It is the poor, disproportionately poor people of color, who have been forced to bear the brunt of the often devastating ills imposed by fracking. Unsurprising, and far from new: “Residents in these poor counties have been under assault for generations,” Alex Lotorto of Energy Justice said.

The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, has been thoroughly documented, and rightly so. Less prominent has been coverage of East Chicago, Indiana, where for decades residents’ homes have rested on lead-contaminated soil. As the New York Times reported in August, “the companies responsible for the contamination” were sued by the Environmental Protection Agency in 2009, but this is little comfort for the more than 1,000 people — including over 600 children — now forced to find a new place to live.

It is impossible to quantify the harm done in such circumstances; but, needless to say, those responsible for the harm harbor few qualms about their actions. One executive reportedly said aloud what most already knew was the case: Poor communities are intentionally targeted because they lack the resources to mount effective resistance.

Thankfully, we have seen in recent weeks that this doesn’t have to be the case — that, when the opposition is sufficiently organized, corporate plunder can be obstructed. Though under-reported in mainstream outlets, the fight over the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline provides a case in point.

North Dakota’s Standing Rock Sioux tribe, joined by many other tribes and activists, has for weeks engaged in direct action in response to Energy Transfer Partners’ desire to move forward with the project, arguing that it would place at risk both the water supply and sacred land. State officials have responded with striking intensity.

“In recent weeks, the state has militarized my reservation, with road blocks and license-plate checks, low-flying aircraft and racial profiling of Indians,” wrote David Archambault II, the chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. “The local sheriff and the pipeline company have both called our protest ‘unlawful,’ and Gov. Dalrymple has declared a state of emergency.”

Last week, as Common Dreams reported, over twenty protesters were arrested in “a military-style raid” which “interrupted a peaceful prayer ceremony.”

Far from dispiriting, such a vicious response to nonviolent demonstrations of this kind show how threatening organized protest is to corporations and their partners in government; though they claim to fear chaos, disorder, and violence, what corporate forces really fear is mass solidarity expressed through courageous acts of civil disobedience.

Of course, the protests at Standing Rock are not isolated acts, and they are, as Sarah Jaffe observes, “bigger than one pipeline.”

“We all have similar struggles, where this dependency this world has on fossil fuels is affecting and damaging Mother Earth,” David Archambault II told Jaffe. “It is the indigenous peoples who are standing up with that spirit, that awakening of that spirit and saying, ‘It is time to protect what is precious to us.'”

Never has such action been more necessary.

The science tells us that we have reached a critical moment; as Naomi Klein has argued, “no gradual, incremental options are now available to us.” Researchers agree, and some have joined the call for “radical change” that goes far beyond the agreements reached in Paris.

But such radical change cannot take place in the absence of mass anti-capitalist movements that recognize the interplay between economic interests and environmental degradation. The leaders of the struggle for a sustainable, equitable future will not, therefore, be corporate executives and billionaire philanthropists, with their deep ideological commitments to the economic order that so enriched them and their businesses. Rather, leading the way will be the indigenous communities that have for so long been forced to endure relentless dispossession in the name of business.

As Noam Chomsky has observed, “The countries that have driven indigenous populations to extinction or extreme marginalization are racing toward destruction.” And, he adds, “countries with large and influential indigenous populations are well in the lead in seeking to preserve the planet.”

If “water is life,” as the Sioux saying goes, an economic system that poisons water for profit is life’s contradiction — it is a system of destruction, a “suicide economy,” that must be dismantled.

“Ultimately, the ‘success’ or otherwise of the Paris climate talks appears unlikely to challenge the fundamental dynamics underlying the climate crisis. Dramatic decarbonization based around limits upon consumption, economic growth, and corporate influence are not open for discussion,” conclude scholars Christopher Wright and Daniel Nyberg. “Until this changes, the dominance of corporate capitalism will ensure the continued rapid unraveling of our habitable climate.”

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License

“In the conference’s preparatory meetings,” Korten writes, “corporatists … proposed that to save nature we must put a price on her.” Clearly corporatists are locked into a vision which only recognises the existence of something when it becomes a commodity otherwise it is nothing. No wonder they cannot help but destroy the world in pursuit of such a narrow view of life.