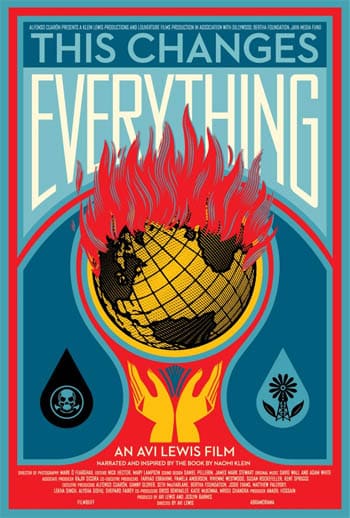

This Changes Everything

This Changes Everything

A film by Avi Lewis

Narrated and inspired by the book by Naomi Klein

reviewed by Kate Aronoff

republished under a Creative Commons license, from YES! Magazine

“What is the core problem?” Naomi Klein is in rural Greece, interviewing Mary Christianou against a backdrop that could have been pulled from aGladiator dream sequence.

Christianou looks surprised, letting out a slice of nervous laughter. “You want me to say it on camera?”

Off-camera, Klein affirms.

“I would say it’s the economic system … capitalism, I guess,” Christianou says, fixing her gaze someplace off in the distance.

After Canadian mining company Eldorado started angling to build an open-pit gold mine in her mountainside backyard, Christianou and a handful of other locals formed the Halkidiki Citizens’ Committee to fight the proposed 31,700-hectare—or 122 square-mile—project, slated to turn a handsome billion-euro profit.

Klein prods: “You’re not sure if you should say that on camera?”

“No,” Christianou explains. “I don’t know if it helps the struggle.”

The exchange is awkward, even forced. But Klein’s digging is for a good cause. Her new film, This Changes Everything, is a message for two audiences: progressives quick to write off the climate movement as a plight of the privileged, and environmentalists who are—like Christianou—reluctant to name the “sputtering machine,” as Klein calls it, that created the mess they’re fighting.

Directed by veteran journalist Avi Lewis, the film eases viewers into a visceral understanding of the conflict laid out in Klein’s best-selling book: capitalism versus the climate. It also offers organizers tools to translate that understanding into a broader-based movement, helping them become better equipped to demand solutions at the scale of the problem. What seems clear from the film and the book is that Klein is interested in an altogether better and bigger environmental movement, a movement capable of leaving behind the stodgy backroom politics of groups like the Environmental Defense Fund and Nature Conservancy in favor of something that looks a lot more like a traditional social movement than environmentalism ever has.

Unlike the film’s most natural referents, call-to-action documentaries like Robert Reich’s Inequality For All and Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth, Lewis and Klein tell us what’s wrong through the voices of people already doing something about it, not as hand-wringing experts pining for perfect movements. The difference is owed partially to the creators’ backgrounds. While Reich and Gore sat in the Clinton administration’s backrooms rubber-stamping NAFTA, Klein tagged along with ragtag global justice movement organizers looking to stop similar deals in their tracks, scribbling notes that would eventually find their way into Fences and Windows, an anthology of her reporting from the era.

What really distinguishes This Changes Everything, though, is the remarkable evolution it illustrates in the climate movement’s last decade. In the years since 2006, environmentalists have seen the collapse of cap-and-trade negotiations and climate talks in Copenhagen. The birth of movements like Occupy, campaigns for fossil fuel divestment, and the winning fight against the Keystone XL pipeline have connected North American environmentalism’s mainstream to a spate of anti-corporate, anti-extraction direct action worldwide. Klein refers to this phenomenon collectively as Blockadia: “increasingly interconnected pockets of resistance” led by people who look less like “typical activists” and more “like everyone: the local shop owners, the university professors, the high school students, the grandmothers.”

Neither manifesto nor exposition, the documentary is pure propaganda. As Lewis and Klein explained in a short question-and-answer session following the film’s New York premiere, “Books are really good at laying out a logical argument…films take you places, and demystify the work of changing the world.” The film that flows from this outlook, appropriately, is a borderline hagiographic tale about the power of social movements. Klein spends relatively little time taxonomizing capitalism’s major flaws, choosing rather to break its contradictions down into bread-and-butter issues: a people’s political economy.

At a Heartland Institute conference Klein attends in the film, one climate denier warns that sustainability is a “green Trojan horse whose belly is full with red socialist economic doctrine.” Another skeptic, ClimateDepot.com editor Marc Morano, fears that “If human activity is causing climate change, then almost anything could be justified in terms of government response.” As Klein points out, the irony is that the deniers are right.

Marxist thinkers like John Bellamy Foster and Ian Angus have been teasing out the connection between capitalism and the ecological crisis for decades, though their work has mainly found a home in the academy and among the already committed—certainly not within the environmental movement’s all too white and middle-class mainstream.

What This Changes Everything makes obvious is that a common-sense socialism has existed for decades within communities on these crises’ frontlines, one informed less by a rich theoretical backing than an intimate acquaintance with the ravages of capitalism. From the oil fields of Alberta to the site of a proposed coal-fired power plant in Sompeta, India, the fact that industry’s interests are opposed to that of ordinary people isn’t an abstract point. It is, however, one that climate activists have had trouble communicating, and been reluctant to fully embrace.

Left alone, the fight against global warming might become a rich man’s revolution. Billionaires from Bill Gates to Elon Musk see no contradiction between an end to the climate crisis and free market fundamentalism. In a fascinating interview for The Atlantic recently, Al Gore—with a modest $200 million net worth—opined that capitalism “‘has proven to unlock a higher fraction of human potential’ than any alternative system for making money—and markets are the most efficient way to allocate resources.” Without diving too far into the world of the ever-greener 1 percent, Klein nevertheless asks viewers to choose a side: capitalism or the climate?

No small part of This Changes Everything’s brilliance is in its timing. The book hit shelves just before the 400,000-person strong People’s Climate March late last September, while the film premiered two months shy of the hotly anticipated Paris climate talks this December. For its U.S. audience, the film’s release comes at the same time a conversation about the relative merits of socialism and capitalism has been pried open by our upcoming presidential election.

Some of Klein’s harshest critics in this context have come not from the right, but from pearl-clutching, curmudgeonly believers hostile to change from below. New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait went so far as to compare Klein to House Republicans, decrying “her fervently ideological, anti-empiricist style, and her deep skepticism of the mainstream liberals who believe emissions can be controlled without destroying capitalism.” For all his grand-standing, Chait is right about one thing: “capitalism and climate science are discovering ways to co-exist.”

To change everything, as Klein proffers, we need everyone. An environmentalism with blinders on won’t do the job. For Klein and Lewis, corralling “everyone” means offering a more hopeful vision than melting glaciers and stranded polar bears. This explains their editorial choice to move away from the doom and gloom of climate change and towards things like community-owned renewable projects on indigenous land, and movement-provoked government renewables programs in Germany. Klein and Lewis paint a picture of a post-fossil-fueled, post-capitalist future that seems not only within reach, but like a place where we actually want to live.

Klein ends the film on a note some fatalistic environmentalists—in the tradition of Romantic intellectuals eager to preserve nature from, not for, people—might find disturbing: “What if global warming isn’t only a crisis? What if it’s the best chance we’re ever going to get to build a better world?” Her hope is that the climate crisis can create an opportunity for environmentalists to finally understand power, and highlight—for a broad audience—the deep contradiction between capitalism and a livable planet.

The kind of environmentalism Klein puts forth is a “Trojan horse” for a fundamentally new economic system. And This Changes Everything gives a new generation of organizers some wood to start building the biggest one yet.

Kate Aronoff wrote this review for YES! Magazine. Kate is an organizer and freelance writer based in Philadelphia, whose writing has been published in Waging Nonviolence, Dissent Magazine, AlterNet, and The New York Times. Find her on Twitter at @katearonoff.