by Michael Roberts

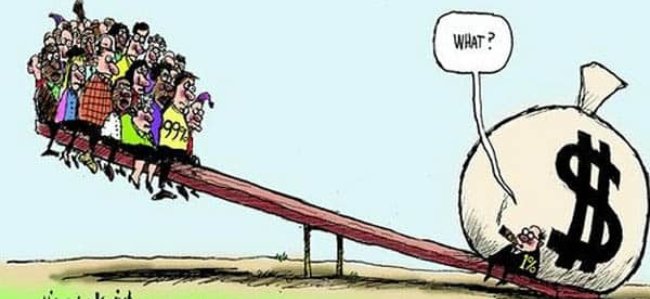

The latest World Inequality Report 2026 reveals the stark cleavage between rich and poor in the world – a division that is getting wider to the extreme. Based on data compiled by 200 researchers organised by the World Inequality Lab, the report finds that fewer than 60,000 people – 0.001% of the world’s population – control three times as much wealth as the entire bottom half of humanity.

In 2025, the top 10% of the global population’s income-earners earn more than the remaining 90%, while the poorest half of the global population captures less than 10% of total global income. Wealth – the value of people’s assets – was even more concentrated than income, or earnings from work and investments, the report found, with the richest 10% of the world’s population owning 75% of wealth and the bottom half just 2%.

In almost every region, the top 1% was wealthier than the bottom 90% combined, the report found, with wealth inequality increasing rapidly around the world. “The result is a world in which a tiny minority commands unprecedented financial power, while billions remain excluded from even basic economic stability,” said the report authors.

This concentration is not only persistent, but it is also accelerating. Since the 1990s, the wealth of billionaires and centi-millionaires has grown at approximately 8% annually, nearly twice the rate of growth experienced by the bottom half of the population. The poorest have made modest gains, but these are overshadowed by the extraordinary accumulation at the very top. The share of global wealth held by the top 0.001% has grown from almost 4% in 1995 to more than 6%, the report said, while the wealth of multimillionaires had increased by about 8% annually since the 1990s – nearly twice the rate of the bottom 50%.

Looking beyond strict economic inequality, the report found that this inequality fuels inequality of outcomes, with education spending per child in Europe and North America, for example, more than 40 times that in sub-Saharan Africa – a gap roughly three times greater than GDP per capita.

And inequality is creating more greenhouse gas emissions The report shows the poorest half of the global population accounts for only 3% of carbon emissions associated with private capital ownership, while the wealthiest 10% account for about 77% of emissions.

Income is distributed unequally everywhere, with the top 10% consistently capturing far more than the bottom 50%. But when it comes to wealth, the concentration is even more extreme. Across all regions, the wealthiest 10% control well over half of total wealth, often leaving the bottom half with only a tiny fraction.

These global averages conceal enormous divides between regions. The world is split into clear income tiers: high-income regions such as North America & Oceania and Europe; middle-income groups including Russia & Central Asia, East Asia, and the Middle East & North Africa; and very populous regions where average incomes remain low, such as Latin America, South & Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

An average person in North America & Oceania earns about 13 times more than someone in Sub-Saharan Africa and three times more than the global average. Put differently, average daily income in North America & Oceania is about €125, compared to only €10 in Sub-Saharan Africa. And these are averages: within each region, many people live with far less.

About 1% of global GDP flows from poorer to richer countries each year through net income transfers associated with high yields and low interest payments on rich-country liabilities, it said – almost three times the amount of global development aid. Inequality is also deeply embedded in the global financial system. Current international financial architecture is structured in ways that systematically generate inequality. Countries that issue reserve currencies can persistently borrow at lower costs, lend at higher rates, and attract global savings. By contrast, developing countries face the mirror image: expensive debts, low-yield assets, and a continuous outflow of income.

The power of capital exerts itself internationally between nations. Excluding countries with a population of less than 10 million, the ten richest countries all receive positive net foreign income on their capital. In contrast, the world’s ten poorest countries are former colonies, most located in Sub-Saharan Africa. They display the opposite trends compared to the richest. Most of these countries pay significant net foreign income to the rest of the world. In other words, these countries are sending out more money than they are receiving from foreign investments. This drain limits their capacity to invest in areas such as infrastructure, healthcare, and education – key to lifting them out of poverty. No wonder they can never ‘catch up’ and close the gap with the Global North.

Can we do anything about reducing inequality? First, in a preface to the report, the Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz repeated a call for an international panel comparable to the UN’s IPCC on climate change, to “track inequality worldwide and provide objective, evidence-based recommendations”. The authors of the report then go on to argue that inequalities can be reduced through public investment in education and health and by ‘effective’ taxation and redistribution programmes. It notes that in many countries, the ultra-rich escape taxation. Tax havens abound around the world. A 3% global tax on fewer than 100,000 centimillionaires and billionaires would raise $750bn a year – the education budget of low and middle-income countries.

The report proposes some other policy measures. One important avenue is through public investments in education and health. Another path is through redistributive programs: “cash transfers, pensions, unemployment benefits, and targeted support for vulnerable households can directly shift resources from the top to the bottom of the distribution.” Tax policy is another powerful lever: introduce fairer tax systems, where those at the very top contribute at higher rates through progressive taxes. Inequality can also be reduced by reforming the global financial system. “Current arrangements allow advanced economies to borrow cheaply and secure steady inflows, while developing economies face costly liabilities and persistent outflows.” Reforms here include adopting a global currency, with centralized credit and debit systems.

The report shows that redistributive transfers do reduce inequality, particularly when systems are well designed and consistently applied. In Europe and North America & Oceania, tax-and-transfer systems consistently cut income gaps by more than 30%. Even in Latin America, redistributive policies introduced after the 1990s have made progress in narrowing gaps. In other words, inequalities would be even worse without such measures.

But the report recognises a key problem. Effective income tax rates have climbed steadily for most of the population, but have fallen sharply for billionaires and centi-millionaires. The elites pay proportionally less than most of the households that earn much lower incomes. This regressive pattern deprives states of resources for essential investments in education, healthcare, and climate action. It also undermines fairness and social cohesion by decreasing trust in the tax system. The answer of the authors is a turn to progressive taxation as it “not only mobilizes revenues to finance public goods and reduce inequality, but also strengthens the legitimacy of fiscal systems by ensuring that those with the greatest means contribute their fair share.”

To summarise, the policy answers offered in the report are: 1) monitoring inequality 2) redistributing income through progressive taxation and social transfers; 3) more public investment in education and health 4) a global currency system.

What is missing here? There is no policy to change radically the socio-economic structure of the world economy – in effect, capitalism is to remain. The owners of capital: the banks, the energy companies, the tech media companies, big pharma, and their billonaire owners – all these are not to be taken over. Instead, we must just tax them more and governments must use the tax money to spend on investing in social needs. So the policy is one of redistribution of existing income and wealth inequality, not pre-distribution i.e changing the social structure that engenders these extreme inequalities, namely the private ownership of the means of production.

In previous studies I have found that the high inequality in personal wealth is closely correlated with inequality in incomes. I found that there was a positive correlation of about 0.38 across the data: so the higher the inequality of personal wealth in an economy, the more likely that the inequality of income will be higher. Wealth begets more wealth; more wealth begets more income. A very small elite owns the means of production and finance and that is how they usurp the lion’s share and more of the wealth and income. And wealth concentration is really about the ownership of productive capital, the means of production and finance. It’s big capital (finance and business) that controls the investment, employment and financial decisions of the world. A dominant core of 147 firms through interlocking stakes in others together control 40% of the wealth in the global network according to the Swiss Institute of Technology. A total of 737 companies control 80% of it all.

This is the inequality that matters for the functioning of capitalism – the concentrated power of capital. And because inequality of wealth stems from the concentration of the means of production and finance in the hands of a few; and because that ownership structure remains untouched, any redistibutive policy based on increased taxes on wealth and income will always fall short of irreversibly changing the distribution of wealth and income in modern societies.

At this point, it is often argued that public ownership of finance and key sectors of the major economies of the world is impossible and utopian – it will never happen short of some popular revolution – which in turn will never happen. My reply would be the adoption of supposedly less radical policies like progressive taxation and/or a step change in public investment; or global cooperation to break the transfer of value and income from the Global South to the rich elite in the Global North, are just as ‘utopian’.

What G7 government in the world is prepared to adopt such policies? None. How close have they got to adopting the report’s policies in the last ten or 20 years? Not close at all – on the contrary, governments have cut taxes for the rich and corporations and raised them for the rest; while public investment in social needs has declined. And is there any global cooperation on ending exploitation by the multi-nationals and banks in the Global South or in ending fossil fuel production and private jets?

The authors of the report say: “Inequality is a political choice. It is the result of our policies, institutions, and governance structures.” But inequality is not the result of “our” policies, institutions and governance structures, but the result of the private ownership of capital and governments dedicated to sustaining that. If that does not end, inequality of income and wealth globally and nationally will remain and continue to worsen.

Leave a Comment