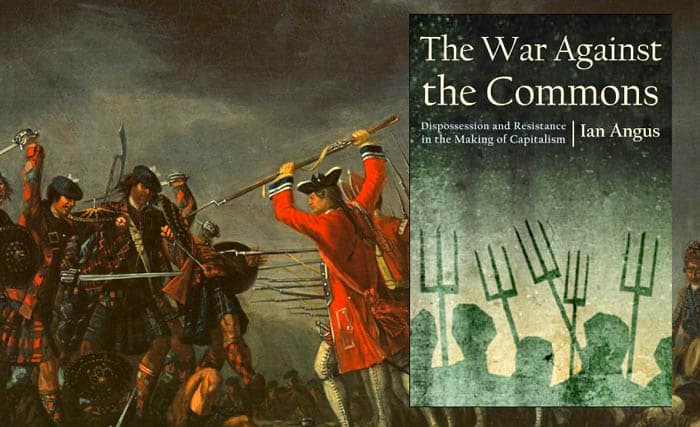

Background image: ‘The Battle of Culloden, April 16, 1746’. By David Morier, 1746.

Ian Angus

THE WAR AGAINST THE COMMONS:

Dispossession and Resistance in the Making of Capitalism

Monthly Review Press, 2023

reviewed by Simon Butler

(Reposted from Green Left, May 10 2023. Simon Butler is an Australian ecosocialist and former editor of Green Left who now lives in Scotland.)

During lockdown I finally gave up smoking for good and took up cycling. Most weekends since (to my own mild astonishment) I’ve sought out and moseyed along the quieter country roads in my local part of lowland Scotland.

The Scottish countryside can be breathtakingly beautiful any time of year, but spring is especially lovely. The cherry blossoms bloom pink and the gorse bloom gold, yet the highest hills might still retain a dusting of snow. Playful newborn lambs prance in the pastures. Crops of bright yellow rapeseed or the deep green of immature wheat blanket the gently sloping fields.

But I now recognize I’ve been blithely pedaling through a crime scene.

Each picturesque estate is a monument to theft and dispossession. Each grand stately home is built upon grand human suffering. Every straight-lined hedge and dry-stone dyke dividing the fields is the residue of a fiercely fought but barely remembered class struggle in which the rich overwhelmed the poor and remade the world.

Ian Angus’s The War Against the Commons vividly retells the story of how land that had been shared for centuries was privatized by force and deception in England, Wales and Scotland. This war against the agricultural commons — known as enclosure in England — lasted hundreds of years and displaced millions.

The same process in Scotland is known as clearance. It took place more quickly in Scotland once agrarian capitalism had been established in England. The Scottish Lowland clearances began in the early 1700s and were complete later that century. The better-known Highland clearances were complete by the mid-1800s.

Enclosure led to the creation of large estates owned by a small elite. This spurred the development of agrarian capitalist enterprise. But enclosure also forcibly created a new class of landless people who could no longer support themselves but had to sell their labor power to survive. Angus says:

“For wage-labor to triumph, there had to be large numbers of people for whom self-provisioning was no longer an option. The transition, which began in England in the 1400s, involved the elimination of not only shared use of the land, but of the common rights that had allowed even the poorest people access to essential means of subsistence. The right to hunt or fish for food, to gather wood and edible plants, to glean leftover grain in the fields after harvest, to pasture a cow or two on undeveloped land — those and more common rights were erased, replaced by the exclusive right of property owners to use the Earth’s wealth.”

Conservative historians portray enclosure as an inevitable modernization, which brought higher agricultural yields. But Angus points to evidence that says the enclosure caused Britain’s poor majority to become significantly poorer and have much less to eat during the 18th and 19th centuries. Wherever enclosure took place it was met by the fierce resistance of the commoners who sought to maintain their customary rights and access to common lands.

This popular resistance took many forms over the centuries. There were large armed revolts involving thousands. There were physical attacks on unpopular landlords or their property. Some repeatedly levelled and burned the enclosers’ hedges, dykes and fences. Other commoners engaged in long-lasting guerilla-style campaigns to steal or kill the livestock that had been placed on former common lands.

The landlords were brutal in defense of their stolen property. During the 1700s, England’s landlord-dominated parliament passed numerous laws that legalized enclosure and criminalized dissent against enclosure. The Black Acts of 1723 created more than 200 new capital offenses. The death penalty applied even to stealing a sheep, felling a tree, killing a deer or poaching from a rabbit warren.

Despite the book’s focus on England and Scotland, Angus does not agree that the origins of capitalism can be understood as an internal British affair. Capitalist development in Britain is closely bound up with Britain’s colonial conquests overseas. Angus says the enclosure process “could not have happened so quickly or thoroughly without the imperial wealth that slave traders, plantation owners, and colonial profiteers invested in British estates.”

Further, Angus says that early British agrarian capitalism would likely have never matured without the mass import of agricultural foodstuffs from the colonies or the outward migration of surplus landless laborers to a New World bloodily cleared of many of its original inhabitants.

This means the dispossession of English and Scottish rural laborers and their transformation into the first modern working class was made possible by the genocide of Indigenous peoples in the Americas and Australia, the labor of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and the undisguised plunder of the Indian subcontinent. Angus’s argument accords with Karl Marx’s, who said in Capital that “the veiled slavery of the wage-laborer’s in Europe needed the unqualified slavery of the New World as its pedestal.”

The War Against the Commons also points out that although enclosures marked the earliest phase of capitalist development, they never ended and never went away. Capitalism has always rested upon twin pillars: the theft of common property and the exploitation of wage-labor. The dispossessed English peasants of the 1600s are the forebears of the campesinos of Chiapas, the Indigenous forest-dwellers of the Amazon, the pastoral Maasai people of Tanzania and the small farmers organized throughout the global South in La Via Campesina. These people are today resisting attempts to take away their traditional lands through fraud and legalized theft.

Enclosure enforced the separation of the poor from the land, creating a lasting antithesis between town and country. This drastic separation has been recreated wherever capitalism has taken hold around the world. In an important chapter, Angus explains why the classical Marxist aim to gradually abolish this uniquely capitalist separation retains its relevance today. He says overcoming the rural/urban division is an inescapable part of repairing capitalism’s metabolic rift, which is driving the global ecological crisis. It is “a call for restoration of the commons on a higher level, as social property rationally regulated by the associated producers.”

The War Against the Commons also includes four very interesting appendices, which expand on some of the central concerns and arguments of the book. I won’t elaborate on the first of these appendices, but I will promise you that once you finish reading it the phrase “Marx’s theory of primitive accumulation” will never again pass your lips.

Other authors have written about the history of enclosure, but Angus’s new book stands out for the refreshing candidness of his worldview, his obvious mastery of the topic and his gift for poignant summary.

It is very much worth retelling this story now because it proves false the most powerful ideological justification of the current system: that capitalism is natural and rational. History shows that societies that practice common ownership and the cooperative allocation of resources have been long-lasting and successful in the past. It’s also a critical time to revisit and rethink this history because capitalism’s never-ending war on the commons is accelerating today, on a far wider scale.

Congratulations on this new book!