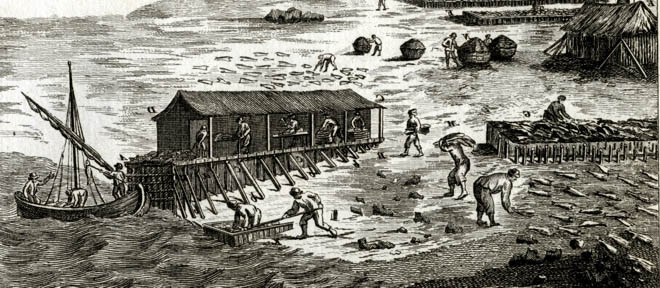

Processing cod in a 16th Century Newfoundland ‘Fishing Room’

by Ian Angus

Historians of capitalism, including Marxists, have paid little attention to a critical event in the evolution of capitalism — the European discovery and expropriation of what Francis Bacon called “the Gold Mines of the Newfoundland Fishery, of which there is none so rich.”

The success of the North Sea and Newfoundland fisheries depended on merchants who had capital to buy ships and other means of production, fish workers who had to sell their labor power in order to live, and a production system based on a planned division of labor. The long-distance fishing operations of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were among the first examples, and very likely the largest examples, of what Marx called manufacture — mass production, without machinery, of commodities that were sold for profit — “a specifically capitalist form of the process of social production.”

In the Fishing Revolution, capital in pursuit of profit organized human labor to turn living creatures into an immense accumulation of commodities. From 1600 on, up to 250,000 metric tons of cod a year were caught, processed, and preserved in Newfoundland and transported across the ocean for sale. That increased production supported a qualitative increase in the volume of fish consumed in Europe — and began the long-term depletion of ocean life that in our time has pushed cod and many other ocean species to the brink of extinction.

I wrote about this important but neglected aspect of early capitalism in a series of Climate & Capitalism posts in 2021. Those drafts, reorganized and considerably expanded, are published this month as the lead article in Monthly Review.

I wrote about this important but neglected aspect of early capitalism in a series of Climate & Capitalism posts in 2021. Those drafts, reorganized and considerably expanded, are published this month as the lead article in Monthly Review.

Click here to read The Fishing Revolution and the Origins of Capitalism.