A report published this week by the UN Environment Program says climate change and land-use change will increase the number of extreme wildfires by up to 14 per cent by 2030, 30 per cent by the end of 2050 and 50 per cent by the end of the century.

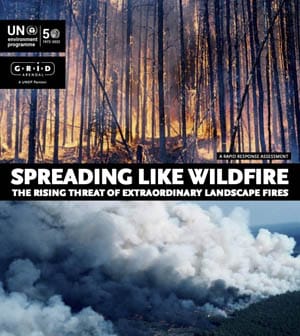

Spreading like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires finds an elevated risk even for the Arctic and other regions previously unaffected by wildfires.

Wildfires disproportionately affect the world’s poorest nations. With an impact that extends for days, weeks and even years after the flames subside, they deepen social inequality and degrade environments.

The report calls on governments to adopt a new Fire Ready Formula, with two-thirds of spending devoted to planning, prevention, preparedness, and recovery, with one third left for response. Currently, direct responses to wildfires typically receive over half of related expenditures, while planning receives less than one per cent.

UNEP Executive Director Inger Andersen:

“Current government responses to wildfires are often putting money in the wrong place. Those emergency service workers and firefighters on the frontlines who are risking their lives to fight forest wildfires need to be supported. We have to minimize the risk of extreme wildfires by being better prepared: invest more in fire risk reduction, work with local communities, and strengthen global commitment to fight climate change”.

Wildfires and climate change are mutually exacerbating. Wildfires are made worse by climate change through increased drought, high air temperatures, low relative humidity, lightning, and strong winds resulting in hotter, drier, and longer fire seasons. At the same time, climate change is made worse by wildfires, mostly by ravaging sensitive and carbon-rich ecosystems like peatlands and rainforests. This turns landscapes into tinderboxes, making it harder to halt rising temperatures.

Wildlife and its natural habitats are rarely spared from wildfires, pushing some animal and plant species closer to extinction. A recent example is the Australian 2020 bushfires, which are estimated to have wiped out billions of domesticated and wild animals.

The restoration of ecosystems is an important avenue to mitigate the risk of wildfires before they occur and to build back better in their aftermath. Wetlands restoration and the reintroduction of species such as beavers, peatlands restoration, building at a distance from vegetation and preserving open space buffers are some examples of the essential investments into prevention, preparedness and recovery.

The report concludes with a call for stronger international standards for the safety and health of firefighters and for minimizing the risks that they face before, during and after operations. This includes raising awareness of the risks of smoke inhalation, minimizing the potential for life-threatening entrapments, and providing firefighters with access to adequate hydration, nutrition, rest, and recovery between shifts.

| TURNING LANDSCAPES INTO TINDERBOXES

(An excerpt from Spreading Like Wildfire) Fire is changing because we are changing the conditions in which it occurs. Not all fires are harmful, and not all fires need to be extinguished as they serve important ecological purpose. However, wildfires that burn for weeks and that may affect millions of people over thousands of square kilometers present a challenge that, right now, we are not prepared for. Lightning strikes and human carelessness have always — and will always — spark uncontrolled blazes, but anthropogenic climate change, land-use change, and poor land and forest management mean wildfires are more often encountering the fuel and weather conditions conducive to becoming destructive. Wildfires are burning longer and hotter in places they have always occurred, and are flaring up in unexpected places too, in drying peatlands and on thawing permafrost. The costs in human lives and livelihoods can be counted in the number who perish in the flames, or contract respiratory diseases from the toxic smoke, or in the number of towns, homes, businesses, and communities affected by fire. A recent study published in The Lancet indicates that annual exposure to wildfire smoke results in more than 30,000 deaths across the 43 countries included in the study. Other species also pay the price: besides a devastating loss of habitat, the smoldering swathes of land left behind in a wildfire’s wake are scattered with the charred remains of animals and plants possibly fast-tracking extinctions. Last year, fires that got out of control in the Pantanal, the World’s largest tropical wetland in Latin America, destroyed almost a third of one of the world’s greatest biodiversity hotspots and there are now genuine concerns that this wetland will never fully recover. Not only can wildfires reduce biodiversity, but they contribute to a climate change feedback loop by emitting huge quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, spurring more warming, more drying, and more burning. The heating of the planet is turning landscapes into tinderboxes, while more extreme weather means stronger, hotter, drier winds to fan the flames. Too often, our response is tardy, costly, and after the fact, with many countries suffering from a chronic lack of investment in planning and prevention. This report makes it clear that the true cost of wildfires — financial, social, and environmental — extends for days, weeks, and even years after the flames subside. To better prepare ourselves and limit the widespread damage done by wildfires, we need to take heed of the clear warnings and recommendations for future action outlined in this report. We must work with nature, communities, harness local knowledge, and invest money and political capital in reducing the likelihood of wildfires starting in the first place and the risk of damage and loss that comes when they do. |