Richard Seymour on the world that is being destroyed and environmental melancholy: ‘We despair, but we do not submit.’

Richard Seymour’s books include The Liberal Defense of Murder and Against Austerity. This article is reposted, with permission, from his excellent blog, Lenin’s Tomb.

“Why add more words? To whisper for that which has been lost. Not out of nostalgia, but because it is on the site of loss that hopes are born.”

— John Berger

“This is the Hour of Lead –

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow –

First – Chill – then Stupor – then the letting go –”

— Emily Dickinson

Robert MacFarlane’s Landmarks is a “counter-desecration phrasebook”: a vocabulary for valuing what we have just as we are about to lose it, just as we are losing it, just as we have already lost it.

Robert MacFarlane’s Landmarks is a “counter-desecration phrasebook”: a vocabulary for valuing what we have just as we are about to lose it, just as we are losing it, just as we have already lost it.

It is as if the living world, of shivelight and suthering tides, of desire lines and whale’s ways, of glaise and drindle, sumping sea-lochs and high headlands, could be saved through re-description. As if it wasn’t already too late.

The last fourteen months have, one after another, broken global temperature records. Floods and droughts begin to assume Biblical proportions. Thousands of species disappear, forever, each year. Even on the mildest prognostications, they will disappear faster and faster.

With a 1.5 degree temperature increase above pre-industrial levels, 20-30 per cent of species risk extinction. With a 3.5 degree increase, the range is 40-70 per cent. We are already at 1.3 degrees, and 4 degrees is the current projected temperature by 2050, even if the Paris Agreement survives.

As the rate of acceleration increases, so does the probability of chaos. Scientists use the metaphor of ‘uncharted territory’ to describe this, since all we know for sure is what we are losing. What will never, ever be seen again.

Walking, in this way, becomes an urgent voyage, a pilgrimage, a visit to a dying patient. A stolen glimpse of what might have been won, had the earth ever been a common treasury.

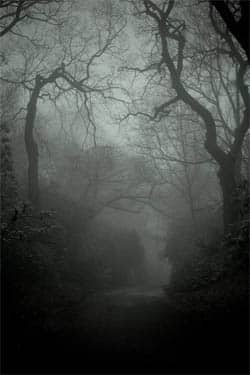

But as Christopher Bollas points out, what we find in the environment is our own unconscious life — not in its narrative, nor in its scenery, but in keywords, objects. The more abstract, nonsensical and formless the terrain, the more we can project into it, and the more evocative it seems. Nothing is more evocative than what theologians, following Psalm 22, call ‘the night season’.

What you find in the burnt edge of a cool morning, the summer shimmer of riparian wetlands, clouds the size of cities soaking in a blue pool, or even in the literary outdoors, the cold mountains of Han-Shan, the freezing Yukon of Call of the Wild — is unconscious meaning.

Worlds of independence, adventure, possibility, decivilization, worlds teeming with potential, closer to birth than death. Oceanic immersion, the feeling of being held, protection. Phobias and anxieties. Screen memories. These private meanings always open out into public meaning. What Renee Lertzman calls “environmental melancholia” begins with lost worlds. Melancholia is a kind of freeze. Mourning is movement, and if you can’t mourn, you gather frost.

One of the biggest obstacles to mourning is that we can’t face our ambivalence: the extent to which we hated the lost object of our love. The ambivalence is complicated. On the one hand, it seems, no matter how much they meant to us, we’re always in some part of us glad to be shot of them. On the other hand, we also hate them for no longer being there. And there are the unconscionable pleasures and benefits that accrue from their absence.

We can hardly help being ambivalent about what we call ‘nature’ and its nemesis, fossil capital. The former means desperate, hard, labouring lives and early deaths. The latter, to the extent that it is coextensive with industrialisation, means comfort, central heating, celerity.

So what is the greenhouse defrosting of arctic sea ice, the bleached death of a coral reef, and the disappearance of thousands of species every year compared to air travel, moon voyages, genetic science laboratories, and the internet. What is the silence of the remote croft, or the murmur of the forest, compared to rising life expectations and falling infant mortality?

The other side of this ambivalence, the nocturnal side, is the knowledge — because this is no mystery, and anyone who wants to know already knows — that we are preparing a mass wake for the human species. It is a planned obsolescence. There are some hubristic billionaires who, by investing in survivalist Xanadus, fancy they will survive the collapse of the food chain and the destruction of habitable territory. Few have the luxury of that conviction. So, put another way, the questions above become: what is species death compared to another fifty years of life for capitalism?

It is useless to berate the insufficiently woke. We are all sleep-walking, and all half-dreaming, even if we dream of being awake. We are all hastening toward the last syllable of recorded time. And the point of melancholic subjectivity is that we are already berating ourselves. Our experience of powerlessness in the face of loss, and isolation before gigantic, tectonic forces, has already become our mantra of self-hate. Adding reproach in the name of the future would only accentuate our resentment of future generations, and our desire to punish them.

But if mourning is movement, it is also work. The work of mourning is not the same thing as the sharp, icicle stab of grief one might feel, while walking, when you suddenly realise that some day and soon, nothing that looks like this world will exist. It is the painful, laborious task of revisiting each memory, each thought, each impression, of what has been lost and, like Poe’s raven, meeting it with the judgement, “nevermore”. Mourning is not an uplifting process. It is a kind of despair, because it means giving up. First chill. Then stupor. Then the letting go.

Only when we can separate the object that has been lost, from what has been lost in it, do we recover. In other words, we give up without giving up. We fully and relentlessly recognise the loss, but we hold onto the qualities we saw in the lost object, because we think we can find a way to revive them in a new passion, a new attachment. We despair, but we do not submit.

“Despair without fear, without resignation, without a sense of defeat,” Berger called it, speaking of the Palestinians and their Nakba. “Undefeated despair.”