The entire premise that justice and sustainability can be purchased in the marketplace is patently absurd.

by Richard Wilk

Richard Wilk is a professor of Anthropology at Indiana University, and a member of American Anthropological Association ‘s Task Force on Global Climate Change.

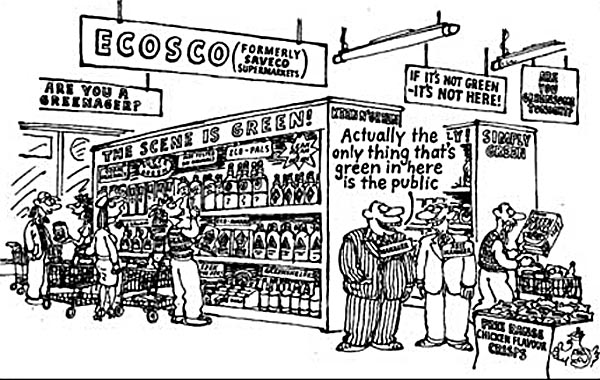

Greenwashing is not just for corporations anymore — it has gone personal. Instead of feeling guilty about the huge gaps between wealthy and poor, the ways consumerism causes global warming, or how our daily pleasures cause rainforest destruction and despoil the sea, we can drink a few cups of fair-trade coffee, eat a rainforest crunch bar and instantly feel better. The consumer marketplace today offers us every kind of ethical, ecological and healthy option we can imagine, from recycled toilet paper to household wind turbines.

Goodness and moral values have been privatized in our post-Reagan-Thatcher neoliberal world. “Green” consumer goods promise the eternal lie of the huckster — that we can have our cake and eat it too, that we can change the world without sacrifice, or any more effort than smarter shopping. Because our gold ear-studs have been “ethically mined” we are absolved from thinking about why we feel we ‘need’ to wear gold at all. We can take expensive vacations in exotic tropical lands, ignoring the poverty around us while we enjoy “sustainable” gourmet meals and an organic mud bath.

Green consumption reduces all of the problems of the world into making the right shopping decisions. If the World Trade Organization is helping bring sweatshop products into our local shop, it is up to us to go find some fair-traded alternative, certified by some impoverished NGO and its idealistic unpaid interns. When outlaw Spanish fishermen chase down the last bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean, we are supposed to find out where the tuna in our local sushi bar came from to make sure we are not partners in crime.

From a critical distance the entire premise that justice and sustainability can be purchased in the marketplace is patently absurd. The proliferation of new consumer choices is just as likely to increase total consumption as it is to lead to actual cuts or measureable reductions. And without the intervention of trusted intermediaries, any system of certification is likely to be co-opted by producers and marketers, to the point where it just becomes another meaningless mark on a package.

Products and brands that do establish some sort of trusted position among consumers are just increasing their brand value in a way that makes them vulnerable to take-overs and buy-outs. This happened with iconic counter-cultural brands in the USA like Kashi (now Kellogg) and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, which is now a division of Unilever, though you would not know this from the company website. In a marketplace now awash in green paint; candy bars have become “granola bars” from a fictional “Nature Valley,” which is actually the factory of mega-corporation General Mills.

This is hardly the first time that frugality and morality become fashionable in the marketplace. Non-slavery sugar was an early example of social marketing, followed by the Salvation Army’s manufacture of matches made without the white phosphorus that poisoned match factory workers. At the higher end of the social scale, examples include Marie Antoinette’s little farm at Versailles and Theodore Roosevelt’s sojourn on a western ranch, where he toughened himself and regained his masculinity. Generations of the middle class have sent their children off to summer camps to live simply with nature, and to colleges where they experience temporary poverty, hopefully relieved after graduation. Even ancient Babylonian city-dwellers worried that opulence was spoiling their children, and by the time of the European Renaissance, a large fraction of the population was living in the enforced frugality of convents and monasteries.

A hunger for authenticity, direct experience, and knowledge of origins and production have been deeply embedded in elite consumption for hundreds of years, for example in the connoisseurship of French wines and foods like truffles and caviar. Even the ancient Romans loved the “simple life” on their rural villas, at the same time that they sought the finest and rarest spices, clothing, cosmetics and wines. Nostalgia for an imagined past or a perfect landscape has driven consumption, and tinged it with a deep sense of morality for a long time, perhaps since the very first cities of the late bronze age.

What is different about eco-shopping in the contemporary world is that the problems it tries to address are so much larger and more serious than the issues faced by previous generations. More people live in absolute poverty, without even the ability to feed themselves on subsistence farms, than ever before in human history. Consumers have never faced such a wide range of dangers from a witches brew of toxic chemicals, resistant diseases, and engineered organisms. And we have rapidly burned through hundreds of millions of years of sequestered carbon in the form of fossil fuels, changing the composition of the planet’s atmosphere in a gargantuan uncontrolled experiment in climate regulation.

Another difference between our own consumer culture and that of our ancestors, is that now we know so much more about the way our consumption connects us to each other, to our own health and that of the planet. For the first time we can see, or even talk to the people who grow our gourmet coffee, weave our artisanal rugs, and put beads in our cornrows on a holiday beach. This marvelous network of information leaves consumers more exposed to moral fault than ever before, and makes the burden of moral behavior heavier and more perilous. Often the only choices seem to be tokenism – making changes that are more symbolic than substantive – or cynicism grounded in the experience of falling for new trends or solutions that turn out to be misguided, co-opted, or fraudulent.

Those of us concerned with the real impacts of global consumer culture are stuck in the territory between cynicism and tokenism, trying to think more productively about the kinds of strategies that can make a symbolic and material difference. We hope that the passive activism of green (or greenish) consumption can connect with more overtly political activities, from changing local health codes to allow edible landscaping or backyard chickens, seeking further education on environmental issues, or backing green candidates in elections. Green consumerism may play a key role as a kind of “gateway drug” for people who would otherwise be disengaged from any action at all.

Changing your brand of toilet paper requires no more than a minimal commitment of time and money, but it might provoke some questions about the origins and impacts of other consumer goods. Fear of bad publicity or consumer boycotts has also been a powerful force in getting the attention of manufacturers and service-providers, eliciting many levels of response to issues of sustainability.

But there is a thin and often invisible line between green actions and greenwashing. Sometimes we can only tell in retrospect if actions by governments and corporations really do reach the intended goal of reducing waste, increasing efficiency and promoting public health. At what point do thin coats of green paint add up to something more substantial and self-supporting?

As the CO2 measuring instruments on Mauna Kea in Hawaii edges towards 400 PPM, it is time to think about more direct actions that we can take to dramatize the dilemma of consumer culture. We need to stop using abstract terms like “growth” and “industrial output” when we talk about the causes of climate change. Voluntary actions by an enlightened few are not going to change the amount of Co2, methane and soot pouring into our air. Even a carbon tax is not going to solve our problem, since the rich have shown over and over again that they are willing to pay higher prices to their yachts, limousines and private jets. Shock treatment through dramatic public events that bring shame on high consumers, and other direct action has to be on the agenda.

Republished, by permission of the author, from Huffington Post, June 14, 2013

Or better yet, DON’T get a car, if you live in an urban area. Walk, cycle, take public transport and fight for better public transport, walkability, proper cycle lane infrastructure. And hire a carshare car if you need one for “heavy” shopping or other purposes.

This is not just an “individual choice”. It is a social combat against lethal carcentric development.

Many consumers want to seriously lower their footprint on the planet and are willing to do what it takes to do so. They are hungry for practical, serious ways to do this. They need options that are real! Where do they find these options?

This type of article on options would be very helpful.

Thanks for this article, it is very truthful.

I think the author is being rather condescending with people trying to find ethical and ecological alternatives to some ‘consumer goods’. Of course they will market these alternatives, simply because otherwhise they wouldn’t be alternatives at all, people would just continue to consume their usual products. I am thinking here of people trying hard to find ethical and ecological alternatives to phones, computers, cars, etc. These items are not simply luxury items, society as a whole relies on them.

I also see the author talking about tuna and backyard chickens, then accusing producers of products with a much smaller ecological impact of greenwashing. If you truly believe not all animal products have a giant ecological impact and ‘organic meat’ or ‘wild-caught fish’ are not greenwashing you are not being very critical.

The time for deeper commitments to changes in our lifestyle is now. Reduce the amount of flying we do, work to avoid buying cheap clothing that we throw away after two months because the fashion has changed, while they may be cheap they come at a significant environmental cost in growing, processing, manufacturing, transporting and then disposing of. All that water, fertilizer and fuel used plus labor often at poverty levels of remuneration etc.

Time to seriously walk the walk and not just talk it. That electric hybrid, unless you are going to travel over 30,000 miles a year in it for the next two decades don’t buy it. Get a simple but efficient gasoline powered car instead. Doesn’t fit with the concept of going green but going green means staying away from the greenwashing that surrounds their advent in the market.