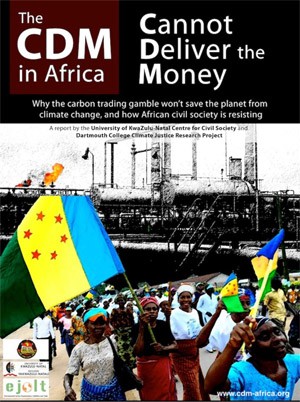

A new report, The CDM in Africa Cannot Deliver the Money (PDF), produced by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Centre for Civil Society and Dartmouth College Climate Justice Research Project, explains in full detail why the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is failing.

A dozen researchers from around the globe, under the guidance of Professor Patrick Bond offer detaoled analysis and case studies from South Africa, Niger, Kenya, Mozambique, Ethiopia, the DRC and Tanzania to show that CDM is causing more harm than good to Africa –the continent that contributes the least to climate change but that suffers the heaviest toll.

A dozen researchers from around the globe, under the guidance of Professor Patrick Bond offer detaoled analysis and case studies from South Africa, Niger, Kenya, Mozambique, Ethiopia, the DRC and Tanzania to show that CDM is causing more harm than good to Africa –the continent that contributes the least to climate change but that suffers the heaviest toll.

Disguised as a ‘solution’ to the climate change crisis, the CDM is now creating a second injustice above this existing injustice.

Across Africa, the CDM subsidizes dangerous for-profit activities, making them yet more advantageous to multinational corporations which are mostly based in Europe and the US. In turn, these same corporations can continue to pollute beyond the bounds set by politicians especially in Europe, because the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) forgives increasing pollution in the North if it is offset by dubious projects in the South, especially in China, India, Brazil and Mexico (the main sites of CDMs).

But because communities, workers and local environments have been harmed in the process, various kinds of social resistances have emerged, and in some cases met with repression or ‘divide-and-rule’ strategies.

The 105 page report is published by Environmental Justice, Liabilities and Trade (EJOLT), a large collaborative project bringing science and society together to catalogue ecological distribution conflicts and work towards confronting environmental injustice. For more information, see CDMs cannot deliver in Africa.

REPORT SUMMARY AND OUTLINE

At a time the carbon markets face a profound crisis, this report provides critical policy analysis and case documentation about the role of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) in Africa. Instead of providing an appropriate flow of climate finance for projects related to greenhouse gas mitigation, the CDM has benefited large corporations (both South and North) and the governments they influence and often control. South Africa is a case in point, as both a victim and villain in relation to catastrophic climate change.

Many sites of emissions in Africa – e.g., methane from rotting rubbish in landfills, flaring of gas from oil extraction, coal-burning electricity generation, coal-to-liquid and gas-to-liquid petroleum refining, deforestation, decomposed vegetation in tropical dams – require urgent attention, as do the proliferation of ‘false solutions’ to the climate crisis such as mega-hydro power, tree plantations and biofuels. Across Africa, the CDM subsidizes all these dangerous for-profit activities, making them yet more advantageous to multinational corporations which are mostly based in Europe, the US or South Africa.

In turn, these same corporations – and others just as ecologically irresponsible – can continue to pollute beyond the bounds set by politicians especially in Europe, because the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) forgives increasing pollution in the North if it is offset by dubious projects in the South.

But because communities, workers and local environments have been harmed in the process, various kinds of social resistances have emerged, and in some cases met with repression or cooptation through ‘divide and rule’ strategies.

Report outline

Chapter One sets the context for the carbon markets and the CDM mechanism, revealing its continuing price collapse and gloomy future prospects.

Chapter Two maps the players in CDM markets and voluntary schemes.

Chapters Three examines South Africa’s pilot CDM fraud and environmental racism in Durban’s Bisasar Road landfill methane electricity project, along with similar trends in Egypt.

Chapter Four dissects the case of Nigerian CDM corruption of local governance, especially where oil companies are receiving subsidies for reducing their Niger Delta gas flaring – an act which by law they are prohibited from doing in the first place.

Chapter Five addresses the emergence of trees, plantations and forests within CDM financing debates, with cases from Uganda, Mozambique, the DRC, Tanzania and Kenya.

Chapter Six is about two failed CDM proposals both involving exploitation of Mozambique’s gas reserves.

Chapter Seven discusses the way megadams are being lined up for CDM status, with case studies from Ethiopia and the DRC.

Chapter Eight considers the rise of the Kenyan and Mozambican Jatropha biofuel industries.

All these cases suggest the need for an urgent policy review of the entire CDM mechanism’s operation (a point we made to the United Nations CDM Executive Board in a January 2012 submission), with the logical conclusion that the system should be decommissioned and at minimum, a moratorium be placed on further crediting until the profound structural and implementation flaws are confronted.

The damage done by CDMs to date should be included in calculations of the ‘climate debt’ that the North owes the South, with the aim of having victims of CDMs compensated appropriately.

WHAT IS A CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM?

(excerpt from the report)

CDMs were created to allow wealthier countries classified as ‘industrialised’ – or Annex 1 – to engage in emissions reductions initiatives in poor and middle-income countries, as a way of eliding direct emissions reductions. Put simply: the owner of a major polluting vehicle in Europe can pay an African country to not pollute in some way, so that the owner of the vehicle is allowed to continue emitting. In the process, developing countries are, in theory, benefiting from sustainable energy projects.

The use of such ‘market solutions’ will, supporters argue, lower the business costs of transitioning to a post-carbon world. In a cap and trade system, after a cap is placed on total emissions, the high-polluting corporations and governments can buy ever more costly carbon permits from those polluters who don’t need so many, or from those willing to part with the permits for a higher price than the profits they make in high- pollution production, energy-generation, agriculture, consumption, disposal or transport.